Overview

How did African American, Latino, and white day laborers experience Atlanta's transformation to an international metropolis at the cusp of the twenty-first century? In addition to documenting the conditions under which day laborers lived and worked, this essay reveals the ways in which attorneys, activists, and others sought to improve day laborers' working conditions. Historical, ethnographic, and geographic methods guided the research, and the result is a rich array of photographs, audio clips, and maps that accompany the written text. In particular, Tom Rankin's 1988 photographs of day labor agencies illuminate a method of securing employment that generally remains, like day laborers themselves, in the shadows.

Introduction

I left Guatemala May 28. I had problems crossing into Mexico from Guatemala. Mexican officials threw me back eight times but I kept trying. They tried to get me the last time but I jumped off a train and fell down a riverbank and they couldn't catch me. I was in the army in Guatemala, so I had a compass. I took a train through Mexico. I swam across the Rio Grande. I didn't use a coyote. I got mugged on the Mexican side. They cut my head with a knife. They took my shoes and my gold necklace and then they threw me in the water. They cut me because I fought back. There were days when I didn't have water and I was eating cactus. Oh, the sun! I walked from Laredo to Houston. I would walk until I couldn't walk anymore and then sleep and keep walking. I came in a train to Atlanta . . . Caught it in Houston. When I grabbed a hold of the train, I didn't do it very good, but I held on and the train dragged me and that is why I am so scratched.

— Francisco Castillo1Francisco Castillo [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 10 September, 2003. Francisco Castillo's words are a composite narrative based on this interview and an unrecorded interview with the author on 10 September 2003. Additional Castillo quotes in this essay are composites from these interviews.

On the hot and humid morning of September 10, 2003, thirty-three-year-old Francisco Castillo, a hungry, bruised and scarred man of slight build had just arrived at the day labor hiring hall in Canton, Georgia, after a three-month journey from Guatemala.

Terry Easton, Waiting for work. Buford Highway, Chamblee, Georgia, December 2004.

A three-inch scar near the crown of his roughly-shaven head, the scabs on his soiled hands, the cuts across the length of his back, the swelling at the base of his left leg, and the odor of his sweaty, unwashed clothes bear witness to his journey. Canton, population just under eight-thousand and the seat for Cherokee County ("Where Metro Meets the Mountains") approximately forty miles north of downtown Atlanta, is not Francisco's final destination.2Cherokee County Chamber of Commerce, "Discover Cherokee!" https://cherokeechamber.com. "My uncle works carpentry, and he'll try to get me a job. I made tables and chairs in Guatemala, so I know how to do that," he says with anticipation. Francisco is trying to get to the city of Chamblee where his uncle lives in an apartment with four others. Chamblee is about thirty miles southeast of Canton and one of metro Atlanta's several ethnic enclaves for recently-arrived and settled immigrants from Mexico, Central America, and South America.

Francisco hopes to work in Atlanta for two or three years and send money to his children in Guatemala. In order to save money and arrive in the United States free of debt, Francisco decided not to pay a coyote (or a "pollero" as some border crossers call them) to help him get from Santa Cruz, Guatemala to Chamblee. He made this decision understanding the risks. Francisco knew it might take him two months to complete his journey, so he packed about four-thousand dollars. He paid for transportation and food in Mexico, and he offered bribes to Mexican officers who beat his chest with weapons. By the time "pirates" jumped him at the Mexican side of the Rio Grande and robbed him of his necklace and shoes, he had no money left for them to steal.

After crossing the border into the United States, Francisco passed through Houston, in route to Atlanta. He sometimes asked people for water, while other times thirst forced him to drink what remained in discarded plastic water bottles. For food he sometimes rummaged through garbage cans after waiting for people to throw away their unwanted breakfast, lunch, or dinner. "A police officer saw me do it one time and told me to get out of there," he growls, mimicking the officer's reproach. Fearing that he might be arrested and deported, Francisco did not dare steal water or food. People sometimes gave him food when he asked; other times they told him to go see immigration officials. When he arrived in Canton, somebody gave him five dollars to buy food, and he ate a meal for the first time in three days: bread and a rice-enriched drink.

After arriving at a downtown Atlanta train station, Francisco found his way to the hiring hall through a series of drop-offs and handovers. This chain of concerned people included nuns who told him about Ministries United for Service and Training and their programs to assist people in need, including a hiring hall where men wait for work. This was a fortunate turn of events for Francisco. Eva Villafañe, coordinator of the hiring hall, offered to place him on the sign-up sheet for day labor and searched for a place for him to sleep for the evening. Despite having no money and having slept under a bridge near downtown Canton the night before, Francisco refused her offer. He was anxious to find his uncle in Chamblee so he could call his family and let them know he had arrived safely. He hadn't talked with them since May. "They might think I'm dead."

This episode in the life stream of Canton, a city struggling with the push and pull of economic, political, and familial forces of migrant workers passing through or settling in, highlights one story among many. Gone are the days of white workers filling positions at Canton Cotton Mills (later Canton Textile Mills) as a major source of employment in this town that emerged as a center of textile production in the twentieth-century South. The mills closed in 1981. With the passing of textiles Canton has become a place where Latin American workers at day labor sites and the ConAgra poultry processing plant comprise a vital labor market in this Georgia town that is adjusting to its place as an immigrant destination in the northern tip of metropolitan Atlanta.

Passing time waiting for work. Canton, Georgia. Photo by Terry Easton, August 2003.

If Francisco Castillo is unable to find his uncle in Chamblee, he may end up working as a day laborer like thousands of others in the metro region. He would rather not do this. In Houston, he went to the street for work and a man in a pickup truck asked if he could do carpentry. He and a group of other waiting men were hauled away to work with the promise of ten dollars an hour. At the end of the day, the boss ("el patrón," "el jefe") turned to Francisco, rolled up a wad of money, gave it to him, and sped away. Francisco counted thirty-three dollars, about one-third of his expected pay. Angered, he vowed he would never work as a day laborer again.

Francisco Castillo is one of thousands of immigrants who have traveled through or settled in contemporary Latino gateway cities such as Atlanta since the beginning of the twenty-first century. Atlanta is not a final destination for many, but rather a place to occupy for a year or two, make enough money to send a portion to their families back home, pay rent, buy food, and establish some semblance of normalcy and stability while living a temporary life in a region where Spanish-speaking migrants and immigrants are variously welcomed, tolerated, and scorned. In recent years, Latin American immigrants comprised the largest population of new arrivals to Atlanta: "the population grew from 26,000 in 1980 to 108,000 in 1990 to 250,000 in the year 2000."3Mary Odem, "Latin American Immigrants, Religion, and the Politics of Urban Space in Atlanta," in Mexican Immigration to the U.S. Southeast: Impact and Challenges, ed. Mary Odem and Elaine Lacy (Atlanta: Instituto de Mexico, 2005), 141.

Immigrant population growth was not the only demographic shift in Atlanta: From 1980 to 2000, in-migrants from the U.S. and refugees from around the world also settled here. During this period, Atlanta's population grew from two million to more than four million.4Andy Ambrose, "Atlanta," The New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/atlanta (8 December 2005). By 2004 Atlanta was the ninth-largest metropolitan area in the United States. The demographic shifts that accompanied this population boom meant that Atlanta could no longer be divided along the traditional racial and ethnic lines of black and white.

International Atlanta: Contingent Work in a Global Economy

The rise of temporary work in the 1970s, coupled with Ronald Reagan's fiscal and social policies of the 1980s, created particularly hard times for low-wage workers in the closing decades of the twentieth century.5Sam Rosenberg and June Lapidus, "Contingent and Non-Standard Work in the United States: Towards a More Poorly Compensated, Insecure Workforce," in Global Trends in Flexible Labour, ed. Alan Felstead and Nick Jewson (Basingstoke, England: Macmillan Business, 1999), 78-79. Increasing globalization and economic uncertainty in the 1990s and beyond promised that the wages, rights, and protections of low-wage workers would become even more tenuous.6Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989), 128-130. During this period, the Atlanta metropolitan region was transformed into a convention, tourist, and employment destination. The construction and renovation of office towers, shopping malls, universities, sports arenas, airports, hotels, homes, and venues for the 1996 Olympic Games significantly altered the size, shape, and scope of Atlanta's place in the national and international economies.

Saskia Sassen's research on cities in the late twentieth century demonstrates that in many large metropolitan cities with highly developed global processes (including rapid and mobile transnational financial transactions, access to multiple markets and administrative and production sites, and a large transitory immigrant population) the gap between the rich and the poor widened through the simultaneous development of a large low-wage informal or service economy and a high-income commercial or business economy. In these "transnational spaces within national territories," new socio-spatial economic configurations (including gentrification, suburbanization, and labor segmentation) increased inequality, especially in cities already devastated by manufacturing decline.7Saskia Sassen, Cities in a World Economy (Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 1994), xiii. Historically a transportation hub, Atlanta was never a major manufacturing center, but in this deeply divided, class-based social and cultural context, the growth of advanced producer services benefited only certain segments of the labor force, while increasing numbers joined the contingent workforce. Handsomely compensated financiers, technocrats, entrepreneurs, and other mid-to-upper-level professionals benefited from this contingent labor force in (at least) two ways: 1) By utilizing the as-needed labor force in the operation of their own business, and; 2) By utilizing the as-needed (low wage) labor force in their personal lives in the "production of lifestyle" through purchasing "services" such as child care, housecleaning, landscaping, home renovation, personal grooming, and dining out.

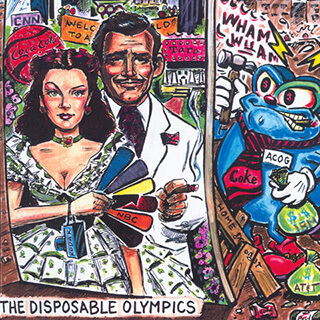

Sociologist Peirrette Hondagneu-Sotelo reminds us that globalization's high-end jobs breed low-paying jobs.8Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 6. Low-wage workers (day laborers among them) have a hand in the production of lifestyle. Such was the story in urban and suburban enclaves across Atlanta's vast landscape at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Economic, social, and political processes set the stage for the growth and development of a large, diverse, and geographically scattered day laboring population in Atlanta.Because of the sheer number of day labor positions and the diversity of methods for procuring employment, some contingent workers called Atlanta "day labor city." A primarily male population group, Atlanta's day laborers earned from minimum wage up to roughly ten dollars an hour depending on experience, skill, training, employer generosity, and luck. Hired and fired with relative ease in manual trades and industries that relied on flexible employment, these "disposable" workers often completed their work assignments under hazardous conditions without many of the workplace benefits accorded the "regular" employees alongside whom they sometimes worked.

Terry Easton, Front door at Labor Ready labor agency. Decatur, Georgia, October 2004.

The temporary staffing industry (a central form of day labor employment) has firm roots in the anti-union South, especially in "right-to-work" states such as Georgia. The Georgia Department of Labor indicated that temporary staffing employment tripled in the state between 1980 and 1985.9Randall Williams, Hard Labor: A Report on Day Labor Pools and Temporary Employment (Atlanta: The Southern Regional Council, 1988), 14. Accurate demographic and statistical information on Atlanta's day laborers is difficult to procure not only because many day laborers are undocumented and therefore go unreported, but also because it was not until February of 1995 that the United States Department of Labor began collecting detailed data on contingent employment. For a vignette taken from Hard Labor see Williams' "Living the Day Labor Life." In Atlanta, the number of temporary staffing agencies doubled between 1978 and 1988.10Ibid., 13. For Kay Sheats, president of Industrial Labor Service, it was the dearth of unions that drew her temporary staffing company to Atlanta in 1987: "We researched Atlanta. We knew the growth. I know the business here. Any time there's no unions, there's the need for temporary work."11Ibid., 24. Labor Ready Real Estate Director, Vice President, and Purchasing Treasurer Bruce Marley discussed the growth of their temporary staffing offices in Atlanta: "We really like metro Atlanta. It's a good market for us."12Starner, "Help Wanted: Labor Ready Finds Workers Where They Live," Site Selection Magazine – Online (July 2001), https://siteselection.com/issues/2001/jul/p420/.

Within the broad spectrum of contingent work, day laboring was characterized by low wages, dangerous or unpleasant working conditions, and lack of job-related benefits. Day laborers were generally the poorest and most vulnerable of all contingent workers. Homeless men, former prisoners, unemployed workers, laid-off workers, part-time workers, veterans, immigrants, undocumented workers, drug addicts, and other people on the social and cultural margins sought work as day laborers. Even though these workers were peripheral in their social status, their labor was not peripheral to Atlanta's growth and development. Day laborers seldom knew in advance how each workday would begin and end, and the dual contingencies of labor and survival unfolded while they attempted to find work at the margins of Atlanta's economy.

Most day laborers yearned for a full-time position with a regular schedule and benefits; a smaller number preferred the flexible employment arrangements associated with day labor. It was common for Latino day laborers to characterize their employment goals as such: "It's better to look for a stable job. Somebody does not come from Mexico to work for one or two days a week. They come to work for more than that. And this is really unstable and you can work for one day and not work for four and work for two days and not work for more." Working steadily for a company, he says, is better: "It's a secure job and if you get hurt they will help you out."13Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 22 April 2004.

Trying to find good wages, safe and clean working conditions, and possibly a full-time position with a regular schedule and employment benefits, day laborers conducted their daily search for work by determining which employment strategy would most likely fulfill their particular employment goals. Atlanta's day laborers used for-profit temporary staffing agencies ("labor pools"), street corners ("catch-out corners"), and non-profit hiring halls to secure work. Experience taught the men that the likelihood of meeting all of their employment goals was unrealistic. Most knew that even if they wanted full-time, regular employment, finding it was possible but difficult. They also knew that they might find themselves working in an unpleasant or dangerous environment. Still they turned out each day (or whenever they could or wanted to turn out) and waited for the opportunity to work. By 2006 roughly thirty for-profit temporary manual labor staffing agencies, forty street corner-waiting areas, and two non-profit hiring halls existed in Atlanta.

Depending upon factors such as skill, training, experience, age, race, ethnicity, English language proficiency, and the particular day labor employment strategy deployed, Atlanta's day laborers were likely to be engaged to work at a construction site, conference center, sports arena, hotel, or private residence. At these work sites, day laborers performed some of the most dangerous and physically-demanding work in Atlanta: they operated machines, demolished buildings, dug ditches, tended lawns, moved stock in and out of warehouses, set up and took down special event seating, loaded and unloaded trucks, worked on assembly lines, and helped build homes, apartments, offices, and shopping centers. Some of these men lived in homes; others lived on the streets or in homeless shelters. Some found refuge in low-rent daily, weekly, or monthly rental units; and still others shared cramped quarters in apartments and sent money to their families in Mexico, Central America, and South America.

De-Centering the City: Uneven Development and the Making of Regional Day Labor Geographies

Until the early 1990s, most labor pools and catch-out corners were in Atlanta's urban core, especially near Techwood Street, the "center of the universe for homeless and unemployed people who were looking for work."14Williams, Hard Labor, 12. As the construction of homes, offices, and shopping centers increased in the suburbs, several labor pools moved from downtown Atlanta to suburban locations. Local upstart labor pools (or branches of regional or national chains) moved there as well. These labor pools were closer to the rising number of Latino day laborers who were settling in suburban regions in large numbers in the 1990s. Several urban labor pools also remained in Atlanta's central business district where homeless shelters and "cat holes" (makeshift sleeping arrangements in parks, under highways, and in patches of forest) continued to provide workers for the day labor marketplace (See Preston Quesenberry, "The Disposable Olympics Meets the City of Hype").

Labor Pools, Atlanta, 1988. Photographer: Tom Rankin

Generally, African American and white day laborers lived in Atlanta's urban core in the 1980s and early 1990s. The collapse of the Texas construction industry, economic and political turmoil in Latin America, and the employment boom that accompanied preparation for the 1996 Olympic Games set in motion an immigration influx that resulted in Latinos settling throughout metropolitan Atlanta in the late 1980s and beyond, particularly in the booming northern suburbs. Affordable housing, readily available employment opportunities, pioneering settlers with strong family and friend networks, Latino-centered businesses and social service agencies, churches, and a bus line that connected Atlanta to Mexico and the U.S. Southwest drew Latinos to suburban counties such as Gwinnett, Cobb, Cherokee, and DeKalb, despite initial settlement in the urban core. By 2000, in two cities along the Buford Highway corridor, Latino population rates were roughly one-half of the total population: Chamblee, 5,384 of 9,552 and Doraville, 4,284 of 9,862.15U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census. The Brookings Institution reported, "As with population generally in the Atlanta metro area . . . immigrants are choosing the suburbs over the city by wide margins. For every new foreign-born resident the city of Atlanta added in the 1990s, its suburbs added [twenty one]."16Brookings Institution, "Atlanta in Focus: A Profile from Census 2000." http://www.brook.edu/es/urban/livingcities/atlanta.htm (November 2003).

As Atlanta's booming economy fueled residential and commercial expansion into the far reaches of the wider metropolitan region, day laborers traveled long distances in search of work. This was especially taxing for workers who lived in the urban core, many of whom traversed county and city borders by bus, train, car, van, or foot to reach worksites or day labor pickup areas. Given the cost of purchase, upkeep, and insurance, few day laborers owned automobiles. The increasing distance between homes (sheltered or unsheltered) and worksites significantly lengthened day laborers' working days, especially in areas where public transportation was limited or unavailable. It was not unusual, for example, for workdays to be ten to fourteen hours long when considering not only the actual labor time but also waiting time and travel time to and from labor pools, street corner waiting areas, hiring halls, and worksites. One African American day laborer characterized his usual workday as a long one: "I get up every morning at four thirty and I don't normally get back until about like seven or maybe eight. Sometimes I have gotten back at ten."17Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004.

Approximately three to five thousand African American, Latino, and white day laborers have been searching for work or working in Atlanta's manual trades and industries on a daily basis since the early 1980s. African American men filled roughly eighty percent and white men roughly twenty percent of day labor positions in the early to mid-1980s. Following the arrival of Latinos beginning in the late 1980s, by 2000 Latinos outnumbered African Americans at catch-out corners, but African American men continued to fill the largest percentage of workers who waited for work at labor pools.

Laboring at the Margins

Each of the three primary methods of securing day labor employment in Atlanta — labor pools, catch-out corners, and non-profit hiring halls — has distinct features that pose advantages and disadvantages for workers.

Labor Pools

For-profit temporary staffing agencies (commonly called "labor pools") were an intermediate entity in the relationship between "clients" and workers. Labor pools profited from the difference between what clients paid them and what they in turn paid day laborers. Contractors or businesses that needed temporary workers, for example, paid labor pools, on average, roughly two to four times the federal or state minimum wage. For their part, labor pools paid workers minimum wage or just above. Labor pools did not offer collective bargaining agreements, and benefits and amenities were few. Located throughout Atlanta, labor pools ranged from independent buildings with traditional storefronts to warehouses with crude furnishings. Labor pools were generally in neighborhoods and business districts with a high prevalence of poverty. As a business strategy, locating in poor neighborhoods was a smart decision: labor pools had easy access to a constant flow of desperate men who had limited means of securing employment in the primary labor market.

Labor pools required men to sign up for work each day as early as five o'clock in the morning. A dispatcher, usually separated from workers by a partition with an opening or a window, controlled the assignment of work. If assigned a job for the day, workers were employees of the labor pool, not the client company, and were paid by the labor pool at the end of each day. These men were hired to do, among other tasks, cleaning, loading, and setting up and breaking down at construction sites, hotels, and restaurants. They generally worked for client companies and subcontractors; seldom did they work for private homeowners. Men used this type of day labor employment for several reasons: they avoided the pushing and shoving associated with street corner pickup sites; they were covered by workers' compensation insurance if they were injured at a job site; their pay could increase if they used power tools or performed skilled work; their employment was "on the books" and fully legal in terms of tax and social security deductions; and barring unusual circumstances, they did not get "stiffed" for their daily labor.

Day laborer Danny Solomon recalls what it was like getting work at Atlanta's labor pools:

There might be a large project going up and a construction company they may call a labor pool and say, 'I need thirty men.' And they'll come up with a price and, you know, the labor pool will say, okay, you need thirty men, and we'll charge you fourteen dollars an hour for each man, okay. And that's normally what it is — twelve, thirteen, fourteen dollars an hour per man, but the man himself only gets whatever the minimum wage is.

If you didn't have a full-time job, that was your only means of supporting yourself or getting any kind of money. You know, I worked on jobs all day long on construction sites, and digging ditches, and stuff like that, and just being dirty and smelly, and garbage and stuff like that, and work eight hours and come back and get paid twenty-five to thirty dollars. But the labor pool might have made one hundred and some dollars off me that day.

Day laborers is just exactly what it is, day labor, labor, meaning slave work man, hauling trash, sweeping, mopping, construction clean up, the hard work, I mean the hard work that has to be done, lifting heavy boxes, which there's no skill involved in that. I've been on construction clean up jobs where I've just pushed a broom all day. All day long eight hours just pushin' a broom. Physically exhausting, emotionally exhausting.

Most of it is construction [work]. But there's a lot of warehouse, also. Unload a truck, load a truck, organize shelves and things like that, anything that's manual labor, sweep, mop, clean the bathrooms, anything that's unskilled and just requires a body. Not too much on the [manufacturing] line, and if it was, you wasn't doin' nothin' but just movin' somethin' from point A to point B, or catching at the end and putting it in boxes. A lot of labor pools send people to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, when the big bundles of papers come down and stack them in the truck, which doesn't require a rocket scientist to do that. Anything that is manual labor that requires strength.18Danny Solomon, interview by author, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 19 April 2005, and 22 April 2005.

Grim working conditions have generally characterized Atlanta's labor pools. In Hard Labor: A Report on Day Labor Pools and Temporary Employment, Randall Williams demonstrated that take-out fees for safety equipment, lunch, and transportation fees often brought day laborers' wages below the federal minimum. Labor pool workers generally earned minimum wage or just above, so additional take-out fees meant that they rarely went home with enough money to support themselves with ample food, clothes, and shelter. "All these charges," Williams wrote in 1988, "are deducted from a check or cash payment that is continually shrinking . . . After deductions, typical take-home pay for an eight-hour job—and many labor pool jobs are less than eight hours—is [twenty to twenty-five dollars]."19Williams, Hard Labor, 18. After eight hours of work and three to four hours of travel time across a large metropolitan region, labor pool workers' days frequently averaged ten to fourteen hours. For many of these men the American Dream of a steady job, employment satisfaction, a home and a car was endlessly deferred. Labor pools provided an opportunity to make money, but also the likelihood of working extremely hard for abysmally low pay. Emmanuel Killen, an African American man who worked at numerous Atlanta labor pools since the early 1980s spoke with vitriol about them: "They are part of the discrimination against lower income or no income or homeless people. I feel like they are nothing but a trap."20Emmanuel Killen, unrecorded interview by author, Atlanta, GA, 10 October 2003.

By the mid-1990s, as evidenced in Atlanta's Hardest Working People: A Report on Day Labor Pools in Metro Atlanta, working conditions for labor pool workers had improved little, if at all, since the publication of Hard Labor in 1988.21Atlanta Labor Pool Worker's Union, Atlanta's Hardest Working People: A Report on Day Labor Pools in Metro Atlanta, (Atlanta: Atlanta Labor Pool Workers' Union, n.d., 1997). This report reveals not only how labor pool workers experienced blacklisting, arbitrary hiring, and discrimination, but also how practices such as illegal charges for transportation and safety equipment continued to bring day laborers' paychecks below federal minimum wage standards. Nearly a decade later, in Workplace Safety in Atlanta’s Construction Industry: Institutional Failure in Temporary Staffing Arrangements, Chirag Mehta found that labor pool workers in Atlanta's construction industry labored in substandard safety conditions and reported a high prevalence of inadequate job training and insufficient safety equipment.22Chirag Mehta et al., Workplace Safety in Atlanta's Construction Industry: Institutional Failure in Temporary Staffing Arrangements (Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Urban Economic Development, June 2003), iii. Workers stated that the most common hazards were laboring at unsafe heights without proper equipment and breathing high levels of dust at jobsites. Twelve percent of the workers in this study reported that temporary agencies never provided safety equipment. Nearly a quarter of the workers surveyed had experienced a serious injury within the previous year and yet most did not receive treatment or workers' compensation for their injuries.23Ibid., iii, iv.

Catch-Out Corners

Day laborers who waited at street corners for jobs were hired to do construction or landscaping work for a contractor or subcontractor, or they might have worked for a private individual doing home repair, lawn care, or loading and unloading furniture. These day labor waiting areas were unregulated or "informal" labor pickup sites. Homeowners used street corner day laborers to perform tasks that they themselves were unable to do because of physical limitations or time constraints. Contractors and subcontractors frequently used street corner day laborers to hold down employment costs to enhance profits. Day laborers ("jornaleros") went to catch-out corners ("esquinas") to get a job for a day or longer. "Connected" sites were located near home improvement stores; "unconnected" sites were in locations without a designated home improvement store nearby but with high traffic flow, good visibility, and a safe means of exiting and entering the roadway. The location of street corner pickup sites was subject to change depending upon a number of factors including city regulations, police harassment, Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) raids, and vehicular traffic.24Created in March 2003 under the Department of Homeland Security, the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement office (ICE) is currently in charge of immigration enforcement duties once managed by the INS.

Day labor pickup sites were located throughout Atlanta, generally near areas where workers lived. Even though many pickup sites were racially segregated, a good number of them were racially mixed, especially in the late 1990s and beyond. Pickup sites in the Buford Highway corridor and the northern suburbs, for example, were comprised primarily of Latinos. Pickup sites in the urban core were comprised primarily of African Americans. This was not always the case: prior to the arrival of Latinos, African American and white men filled the majority of street corner spots, even in suburban cities such as Marietta where the sites eventually became nearly all Latino. Dynamics varied at each street site. At a site in west Atlanta near a truck depot, African American men solicited truckers with offers to help them unload cargo; near a Home Depot in posh Buckhead, Latino, African American, and white day laborers competed with each other for work while private security guards pushed all of them to the perimeter of the parking lot, away from customers; at an intown site in the southeastern quadrant of Atlanta, a federal prison served as an ominous backdrop to the men who waited for labor.

In 2004, an African American man who lived in a homeless shelter in Atlanta's urban core traveled an hour and a half by bus to suburban Marietta to wait for work at catch-out corners. He revealed why he sought work at street corners instead of labor pools: "I come all the way from Fulton County for day labor because down there in Fulton County right now I find it to be very complicated for a man to truly survive down there off what they pay you. Like they only give us like five dollars and fifty cents through the labor pool, and I don't think it's fair. I think people here on these corners, sometimes they have a better chance to deal directly with the contractor or the owner, you know, to do work, especially for a lot of owners that don't want to do [it] themselves, you know, and sometimes when we do that kind of work, they pay us a little bit better than they would if we did it through a labor service. That's why I travel here. I do that just to avoid the labor pool. Even if I come up here and I work four hours, and if I can make eight to ten dollars an hour I do better than I did for a full day service at a labor pool."25Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004.

Advantages of using catch-out corners included workers' ability to negotiate their hourly wage directly with a potential employer; wages generally three to five dollars more per hour than what workers received at labor pools; no deductions from wages for transportation costs or safety equipment fees; a more active approach to securing work compared to waiting at a labor pool; workers could conceivably work more than one job per day; workers who wished to remain anonymous or "invisible" due to their undocumented status were better able to do so. Disadvantages at street corner pickup sites included having to push and shove when competing for work; sometimes not getting paid for work performed; possibly not having workers' compensation insurance if an injury occurred; and making oneself an easy target for police and INS harassment.

At catch-out corners, some nearby business owners and residents viewed day laborers with suspicion, scorn, and fear. As a result, some city councils and county commissions passed ordinances designed to forbid day laborers from congregating in designated areas. A different tack was taken in other locations. In Duluth, the police issued identification cards for day laborers who lived within the city limits, and imposed a fine on “outsiders” who traveled there to wait for work. In Decatur, the city constructed a covered bench that provided a modicum of comfort for day laborers.

Non-Profit Hiring Halls

Non-profit hiring halls and labor pools functioned similarly in that they both provided a place for day laborers to wait for work in a building that shielded them from intemperate climate. Unlike labor pools, non-profit hiring halls did not make money in their intermediary role of connecting workers to employers. Since 2000, four non-profit hiring halls opened in Atlanta, but by 2004 financial difficulties had forced two of them to close. At the two halls that remained open in Canton and Duluth, funding was secured through public and private donations and grants. Atlanta's hiring halls were founded by religious or secular-activist organizations. At the three hiring halls with religious affiliation, all day laborers were welcome regardless of religious beliefs and practices. Latinos comprised the overwhelming majority of day laborers who waited for work at Atlanta's non-profit hiring halls. Generally, homeowners and contractors in the landscaping and construction industries comprised the client base at non-profit hiring halls.

The primary goal of non-profit hiring halls was to offer day laborers a "safe" place to wait for work: a place that shielded them from extreme temperatures, and a place where they were less likely to experience non-payment or underpayment of wages. Workers were assigned jobs each day according to a lottery, and were not allowed to crowd around vehicles when potential employers arrived. A minimum wage rate of roughly twice the federal minimum was established. More than just a place to wait for work, non-profit hiring halls frequently offered coffee, English classes, health workshops, full-time job announcements, immigration and human rights information and workshops, table games, and access to computers. Hiring hall volunteers and employees worked on behalf of day laborers to ensure that workers were paid the full sum of their promised wages. The primary tactic used to prevent such abuse was requiring employers to leave their name and contact information at the hiring hall before securing a worker. A secondary tactic was to mediate on workers' behalf should their employer not pay them. If a worker was not paid wages or was paid below the agreed upon wage, hiring halls contacted employers to recoup the losses. Without a legal staff on site and operating with a small budget, hiring halls were limited in their ability to prevent wage loss, but were still successful in helping some workers collect what they were owed for their labor.

Atlanta's Latino day laborers were especially vulnerable to non-payment or underpayment of wages. A day laborer from Guatemala who had been stiffed explains, "It's always a risk to wait for work, because a lot of times bosses will come and then not pay you . . . Patrόnes sometimes just don't pay."

Terry Easton, Flyer at the non-profit hiring hall, Duluth, Georgia, 2002.

Despite the risk, he turned out for day labor: "People aren't here because they want to be, but because they have to be out of necessity. You just wait for work, and sometimes people rob you."26Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. José Fuentes contemplates one of the bad experiences he had while working as a day laborer: "I don't know why it happens . . . why people disappear and then don't pay you for your work. A guy told me he would pay me 'tomorrow,' but he never paid me. He said he needed to get paid by another guy first. He said he'd pick me up the next morning, but he didn't." José tried to collect the money owed him. He called the person's cell phone and was promised payment, but he never received it. Staff at the hiring hall in Duluth's Calvary Christian Fellowship assisted José, but they were unable to recover his money. "Other guys had been ripped off by him too," he said.27José Fuentes [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 29 July 2003.

Carlos Marín experienced non-payment of wages when he sought work at a street corner. In 2002, he and his brother worked for someone for a week, but they were not paid for their labor. Carlos saw the person at the corner again when he was picking up other workers. The brothers asked the man for their money, but he would not pay them. Following this incident, they turned to Calvary Christian Fellowship for help and then began waiting for work at the hiring hall.28Carlos Marín [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 29 July 2003. In general, hiring halls do whatever they can to secure unpaid wages, but they are not always able to do so.

Workers' regard for hiring halls was evidenced by their willingness to return to them everyday. As their comments demonstrate, the hiring hall was a safe place to wait for work. Tomás Alcántara used a hiring hall instead of the street for many reasons: "The street is very unorganized. I don't like that everybody shoves and pushes and somebody can hurt you. The person that picks you up can actually run you over and it is your fault because you ran in front of him. I like the list here. I like the order. Everybody communicates with everybody very strongly."29Tomás Alcántara [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. Tomás's comments illuminate the atmosphere of respect cultivated at the hiring hall. Javier Lόpez used the hiring hall instead of a street corner to find work because, as he says, "Over here it is easier. Over there everybody runs and I'm not aggressive enough. I don't like that." He also waited for work at the hiring hall because he enjoyed talking to the other men and eating the fifty-cent breakfast soups: "I come here because of these things [and] I like the organization here."30Javier López [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 8 August 2003. Manuel Guzmán concurred, "It is dangerous [at a street corner]. I feel more safe here. People respect you. I like the list. I feel comfortable here."31Manuel Guzmán [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 6 August 2003. Mario Canel feared not being paid when getting work at a street corner: "I do not like the corner; maybe the boss won't pay you."32Mario Canel [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. Guillermo Hernández never waited on a street corner: "[It is] organized here and out of harm's way. They run and shove and push and the people run them over. I've seen it happen. Here it is organized and you can have coffee and soup." Guillermo added that he liked waiting for work at the hiring hall in Canton because the men "fool around and have fun" when they waited for work.33Guillermo Hernández [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. Pickup soccer games, for example, were an established part of the waiting process.

Workers on the Edge

Jeffrey Humphreys of the University of Georgia's Selig Center for Economic Growth reports that day laborers 'are the first to be hired in good times . . . and the first to go down when things slow down."34Rick Badie, "Economic Downturn: Day Laborers Often Wait in Vain," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 29 April 2001, J1.

Kerry Soper, Labor Pooling, Southern Changes Vol. 18, No. 2, Summer 1996, pg. 12. This cartoon critiques the issue of temporary workers brought in to construct and staff the Olympic Village and sporting centers then laid off after the Games' close. From S Zebulon Baker's Whatwuzit?: The 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics Reconsidered.

Without health insurance, financial reserves, employment benefits, and facing a difficult ladder out of the daily-pay marketplace, day laborers' individual and collective workaday lives were sometimes marked by trauma and despair, particularly for African American men. Discrimination and stereotyping had a caustic effect on the men that comprised Atlanta's day labor marketplace. "Dangerous" inner-city African American men with perceived limitations in their "soft skills" (ability to get along with co-workers and customers) and "hard skills" (ability to perform the task at hand) were denied employment in the primary labor market.35Here I draw from two sources that discuss the ways in which perceptions and stereotypes about "inner city" residents, particularly African American men, closed employment avenues. Both studies rely in part on data gathered in Atlanta. See Philip Moss and Chris Tilly, Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001) and Alice O'Connor, Chris Tilly, and Lawrence D. Bobo, Urban Inequality: Evidence from Four Cities (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001). "Illegal" Latinos lacked the identification documents necessary for a driver's license. "Lazy" African American men were overlooked in the day labor marketplace when employers instead chose "hard-working" Latinos.36For a discussion of the ways in which African American construction contractors in Atlanta selected Latino workers over African American workers, see Cameron Lippard, "'Taking Care of Business': The Hiring Practices of African American Entrepreneurs in the Construction Industry" (master's thesis, Georgia State University, 2003). "Compliant" Latinos were denied wages when employers flouted their responsibility to pay them. "Desperate" day laborers of all races, ethnicities, and nationalities encountered verbal abuse (and sometimes physical assault) at street corners and labor pools.

At worksites, day laborers were sometimes asked to perform duties without proper safety equipment and training. Exposure to hazardous chemicals and dangerous machinery, lifting heavy loads, and working several stories from the ground were day laborers' constant companion. For many day laborers, every day is a first day at a job site. Danger is close at hand for both day laborers and regular, full-time workers in these scenarios. Construction, a common day labor job, has been consistently ranked as one of the most dangerous occupations. In the late 1990s the industry divisions related to day labor with the greatest proportion of fatalities were construction (first place) with eighteen percent and manufacturing at fifteen percent (third place). The occupation of day laborers had the fourth greatest proportion of fatalities. In 1999 the fatality rate for roofers was six times the average for all jobs, and for construction laborers, generally the least skilled building workers, it was eight times as high. In Georgia between 1983 to 1995, construction led all industries for the total number of deaths (481) and rate (18.1 per 100,000 workers). Latinos die from workplace injuries at a far higher rate than other workers; in recent years, Latino death rates were twenty percent higher than whites.37Statistical and numerical data in this paragraph can be found in these sources: Suzanne M. Marsh and Larry A. Layne, Fatal Injuries to Civilian Workers in the United States, 1980-1995 (Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Health, 2001); Judith T. Anderson, Katherine L. Hunting, and Laura S. Welch, "Injury and Employment Patterns Among Hispanic Construction Workers," Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 42, no. 2, February 2000: 176-186; Stephen Greenhouse, "Hispanic Workers Die at Higher Rate: More Likely Than Others to Do the Dangerous, Low-End Jobs," New York Times, 16 September 2001.

Hugo Sánchez of Zacatecas, Mexico, worked as a day laborer demolishing stores in Atlanta. Not only was it hard work, but it was also very dangerous. "I was in a crane that took me up very high," he says, admitting that he feared injury or death.38Hugo Sánchez [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 31 July 2003. Thirty-six-year-old Samuel Delgado of Mexico City believes that "most of the jobs [in the United States] are dangerous, especially roofing."39Samuel Delgado [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, Atlanta, GA, 1 August 2003. Additional words by Samuel Delgado in this chapter are from this 1 August 2003 interview. A day laborer recalls an accident at an Atlanta jobsite: "It's hard work. We carry cement and we do things up high and one guy fell one time, and he had lots of injuries, and they didn't pay him, and they didn't do anything to help him."40Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. Delfino Lara adds, "there have been jobs that are dangerous but I just do it anyway . . . painting jobs [at] really high levels where they want us to paint the tallest something around. We just have to do it. Yes, there are risks."41Delfino Lara [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 1 August 2003.

In On the Corner: Day Labor in the United States, a national study released in January 2006, researchers revealed that one-fifth of Latino day laborers had suffered a work-related injury and more than half of those injured did not receive medical care.42Abel Valenzuela Jr. et al., On the Corner: Day Labor in the United States, Working Paper of the Center for the Study of Urban Poverty at the University of California at Los Angeles, January 2006. https://cued.uic.edu/wp-content/uploads/onthecorner_daylaborinUS_39p_2006.pdf (25 February 2006), ii. More than two thirds of injured day laborers surveyed in On the Corner had lost time from work. Seventy-three percent of the day laborers surveyed said they were assigned hazardous tasks like digging ditches, working with chemicals, and working on roofs or scaffolding. The study also revealed that employers often place day laborers in dangerous jobs that "regular" workers are reluctant to do. Fifty-four percent of day laborers who had been injured reported they did not receive medical care because they could not afford it or the employer refused to cover them under the company's workers' compensation insurance.43Ibid., 12, 13. "Day laborers continue to endure unsafe working conditions, mainly because they fear that if they speak up, complain, or otherwise challenge these conditions, they will be fired or not paid for their work," the authors revealed.44Ibid., 12. Jorge Simmonds-Diaz's 1993 research on day laborers waiting for work along Atlanta's Buford Highway corridor indicated that only thirty percent of day laborers used personal protective equipment or received training for safety hazard protection.45Jorge E. Simmonds-Diaz, "Environmental and Occupational Health Survey of a Hispanic Work Group in Atlanta" (master's thesis, Emory University, 1993), 17.

Laboring for Justice in Atlanta's Landscapes of Power

Boosters promoted Atlanta as the "Jewel of the South," "City of the Twenty-First Century," and "Black Mecca." Sociologist Robert Bullard explains that these titles have been misleading. "Atlanta," Bullard wrote in 1989, "is not a Mecca for thousands of low-income persons who call the city home."46Robert D. Bullard and E. Kiki Thomas, "Atlanta: Mecca of the Southeast," in In Search of the New South: The Black Urban Experience in the 1970s and 1980s, ed. Robert D. Bullard (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989), 83. Despite the increasing quantity and circulation of money in Atlanta, low-wage workers struggled to survive in a rapidly changing economic, social, and political milieu. Atlanta's low wage workers did not reap the economic and political rewards accorded more skilled workers during Atlanta's transformation to a global city in the closing decades of the twentieth century. Many day laborers, particularly African American men, worked at or just above minimum wage and lived in penurious conditions. In the early 1980s, day laborers had little political power. By 2005, even though day laborers had found the attention of attorneys, legislators, activists, and workplace justice advocates, effective solutions for their most pressing concerns (low wages, hazardous working conditions, and employer abuse) remained elusive. Viewed through a day laboring lens, Atlanta's growth and development at the cusp of the twenty-first century was impressive but profoundly uneven.47This statement is based on analysis of metropolitan development in Larry Keating's Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001) and Charles Rutheiser's Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (London: Verso, 1996).

Labor pool reform meeting flyer. Atlanta, Georgia. Flyer from Ed Loring's files, Open Door Community, Atlanta, Georgia.

Social movement theorists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward contend that to be poor means to command none of the resources ordinarily considered requisites for social change: money, organizational skill and professional expertise, and personal relations with officials.48Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, The Breaking of the American Social Compact (New York: New Press, 1997), 278. They also argue that the instability of poor people's lives generally prevents sustained efforts for social change. Despite day laborers' general lack of stability and resources, some of their grievances have been addressed through the passage of labor pool legislation, the formation of a union, legal assistance for wage and hour violations, and the development of informational outreach and worker-safety programs.

For this effort to arise, activists had to perceive that the conditions day laborers experienced were wrong and in need of redress. In response to day laborers' harsh working conditions and vulnerability to exploitation and abuse, concerned people from faith-based, non-profit, educational, and governmental organizations rallied in support of various initiatives for economic and workplace justice. In Atlanta's urban core, African American and white day laborers collaborated with attorneys and social justice groups to improve labor pool working conditions. Across Atlanta's regional sprawl, organizations implemented programs to curtail workplace danger and abuse that day laborers experienced throughout Atlanta's vast suburban landscapes.

Day laborers' working lives were formed through employment relations rooted in marginalization, and were often defined by the production of a comfortable lifestyle for middle- and upper-class Americans.

Terry Easton, Flyer for Atlanta Labor Pool Workers' Union, Atlanta, Georgia, May 2002.

Until affluent Americans fully comprehend the ways in which their lives are connected to those of day laborers, contingent workers at the margins will continue to experience abuse and hazardous conditions. To bring significant, lasting change to day laborers' lives, the landscapes of capitalism must be altered through individual and collective work that takes seriously the idea that people who labor deserve fair treatment and a living wage. "Beyond all the legalisms," former Department of Labor investigator Saul Sugerman says, "we all have to be willing to see other people as part of the human race. If we see people as less worthy than ourselves, we're never going to get anywhere."49Daniel Rothenberg, With These Hands: The Hidden World of Migrant Farmworkers Today (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 217. Work, even in its most tedious and grueling forms, should not degrade the human spirit.

Work should be, in Studs Terkel's words, a search "for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying."50Studs Terkel, Working: People Talking about What They Do All Day and How They Feel about What They Do(New York: Random House, 1974), xiii. A fifty-year-old African American day laborer echoes Terkel's sentiments: "I feel like if America would start paying these guys better money, better salaries, and let 'em live more decent than what they're livin', then they will see a better America."51Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. A Latino day laborer observes, "even though we're immigrants we're still human beings."52Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 22 April 2004.

Additional Audio Clips from Interviews

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank those who labored persistently and tirelessly to make this essay rich in content while being pleasant on the eyes and ears. The perceptive and incisive comments of anonymous readers provided excellent suggestions for improving the essay. The Southern Spaces staff, including Sarah Toton, Franky Abbott, Matt Miller, and Mary Battle, brought considerable skill, conscientiousness, and enthusiasm to the multimedia components of this project. Michael Page of Emory University's Woodruff Library harnessed his superb geospatial skills to create extraordinary maps. Tom Rankin graciously offered his arresting photographs of Atlanta labor agencies. Finally, thanks to Allen Tullos for guiding the research from which this essay is based: his encouragement and advice ensured that the voices of day laborers and those who labored on their behalf would be heard.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bacon, David. Communities Without Borders: Images and Voices from the World of Migration. Ithaca: ILR Press, 2006.

Barker, Kathleen and Kathleen Christensen. Contingent Work: American Employment Relations in Transition. Ithaca: ILR Press, 1998.

Breslin, Jimmy. The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutiérrez. New York: Crown Publishers, 2002.

Easton, Terry. "Temporary Work, Contingent Lives: Race, Immigration, and Transformations of Atlanta's Daily Work, Daily Pay." PhD diss., Emory University, 2006.

Feuerstein, Adam. "It's a Different World Once Inside a Labor Pool." Atlanta Business Chronicle, 26 February 1990.

———. "Labor Pools: Bane or Necessity?" Atlanta Business Chronicle, 26 February 1990.

Fine, Janice. Worker Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream. Ithaca: ILR Press, 2006.

Fink, Leon. The Maya of Morganton: Work and Community in the Nuevo New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Gordon, Jennifer. Suburban Sweatshops: The Fight for Immigrant Rights. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Murphy, Arthur D. et al. Latino Workers in the Contemporary South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Parker, Robert E. Flesh Peddlers and Warm Bodies: The Temporary Help Industry and its Workers. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1994.

Peacock, James L. et al. The American South in a Global World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Van Arsdale, David G. "Waiting for Work: A Study of Temporary Help Workers." PhD diss., Syracuse University, 2003.

Waldinger, Roger and Michael I. Lichter. How the Other Half Works: Immigration and the Social Organization of Labor. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003.

Walter, Nicholas et al. "Social Context of Work Injuries of Undocumented Day Laborers in San Francisco." Journal of General Internal Medicine 17, no. 6, (2002): 221–226.

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5w93x0cx

Wilson, William Julius. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

Wheeler, Houston. Organizing in the Other Atlanta: How the McDaniel-Glenn Leadership Organized to Embarrass and Lead Atlanta's Pharaohs to Produce Affordable Housing in Their Community. Atlanta: Southern Ministry Network, 1992.

Web

Cook, Christopher D. "Streetcorner, Incorporated." Mother Jones, March/April 2002.

http://www.motherjones.com/news/feature/2002/03/street_inc.html.

Cook, Christopher D. "Temps Demand a New Deal." The Nation, 27 March 2000.

https://www.thenation.com/article/temps-demand-new-deal/.

Cuadros, Paul. "Hispanic Poultry Workers Live in New Southern Slums." Alicia Patterson Foundation Report. 2001.

http://aliciapatterson.org/stories/hispanic-poultry-workers-live-new-southern-slums.

Fine, Janice. "Workers Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream." Briefing Paper #159, Economic Policy Institute. 14 December 2005.

http://www.epi.org/publication/bp159/.

Greenhouse, Stephen. "Broad Survey of Day Laborers Finds High Level of Injuries and Pay Violations." The New York Times, 22 January 2006.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/22/us/broad-survey-of-day-laborers-finds-high-level-of-injuries-and-pay.html.

Kerr, Daniel and Chris Dole, "Challenging Exploitation and Abuse: A Study of the Day Labor Industry in Cleveland." Report prepared for Cleveland City Council. 4 September 2001.

http://www.popcenter.org/problems/day_labor_sites/PDFs/Kerr&Dole_2001.pdf.

Los Trabajadores/The Workers, directed by Heather Courtney (New Day Films. 2003).

http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/theworkers/film.html.

Ludden, Jennifer. "Cities Confront Clusters of Day Laborers." NPR, Morning Edition, 2 April 2007.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=9277359.

———."Day-Labor Centers Spark Immigration Debate" NPR, Morning Edition, 19 August 2005.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4806486.

"Mexican Immigrant Workers and the US Economy: An Increasingly Vital Role.” American Immigration Law Foundation, Immigration Policy Focus, 1:2 (September 2002).

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/Mex%20Imm%20Workers%20%26%20US%20Economy.pdf.

"More on the Arrested Day Laborers," Athens World (blog), 6 December 2005.

http://www.athensworld.com/2005/12/more-on-arrested-day-laborers.html.

Moser, Bob. "Easy Prey: Domingo Lopez Vargas was an early casualty in the brutal Battle of 'Georgiafornia'." Creative Loafing, 23 February 2005.

http://atlanta.creativeloafing.com/gyrobase/Content?oid=oid%3A18438.

Nik, Theodore and Marc Doussard. “The Hidden Public Cost of Low-Wage Work in Illinois.” Center for Urban Economic Development (U of Ill. at Chicago) with the Center for Labor Education and Research (UC Berkeley). 5 September 2006.

https://cued.uic.edu/wp-content/uploads/HiddenPublicCostMain.pdf.

Revkin, Mara. "Day Laborers Rally in Virginia." The American Prospect, 7 August 2007.

http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=day_laborers_rally_in_virginia.

Sandoval, Carlos. Farmingville, directed by Catherine Tambini and Carlos Sandoval. (Camino Bluff Productions, 2004).

http://www.pbs.org/pov/farmingville/.

Valenzuela, Abel. “Center for the Study of Urban Poverty” UCLA Social Sciences Grant Support.

https://ssgs.ucla.edu/centers/center-for-the-study-of-urban-poverty-csup/.

Valenzuela, Abel, et al. “National Day Labor Study: On the Corner: Day Labor in the United States.” Center for Urban Economic Development (U of Ill. at Chicago). January 2006.

https://cued.uic.edu/wp-content/uploads/onthecorner_daylaborinUS_39p_2006.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Francisco Castillo [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 10 September, 2003. Francisco Castillo's words are a composite narrative based on this interview and an unrecorded interview with the author on 10 September 2003. Additional Castillo quotes in this essay are composites from these interviews. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Cherokee County Chamber of Commerce, "Discover Cherokee!" https://cherokeechamber.com. |

| 3. | Mary Odem, "Latin American Immigrants, Religion, and the Politics of Urban Space in Atlanta," in Mexican Immigration to the U.S. Southeast: Impact and Challenges, ed. Mary Odem and Elaine Lacy (Atlanta: Instituto de Mexico, 2005), 141. |

| 4. | Andy Ambrose, "Atlanta," The New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/atlanta (8 December 2005). |

| 5. | Sam Rosenberg and June Lapidus, "Contingent and Non-Standard Work in the United States: Towards a More Poorly Compensated, Insecure Workforce," in Global Trends in Flexible Labour, ed. Alan Felstead and Nick Jewson (Basingstoke, England: Macmillan Business, 1999), 78-79. |

| 6. | Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989), 128-130. |

| 7. | Saskia Sassen, Cities in a World Economy (Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 1994), xiii. |

| 8. | Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 6. |

| 9. | Randall Williams, Hard Labor: A Report on Day Labor Pools and Temporary Employment (Atlanta: The Southern Regional Council, 1988), 14. Accurate demographic and statistical information on Atlanta's day laborers is difficult to procure not only because many day laborers are undocumented and therefore go unreported, but also because it was not until February of 1995 that the United States Department of Labor began collecting detailed data on contingent employment. For a vignette taken from Hard Labor see Williams' "Living the Day Labor Life." |

| 10. | Ibid., 13. |

| 11. | Ibid., 24. |

| 12. | Starner, "Help Wanted: Labor Ready Finds Workers Where They Live," Site Selection Magazine – Online (July 2001), https://siteselection.com/issues/2001/jul/p420/. |

| 13. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 22 April 2004. |

| 14. | Williams, Hard Labor, 12. |

| 15. | U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census. |

| 16. | Brookings Institution, "Atlanta in Focus: A Profile from Census 2000." http://www.brook.edu/es/urban/livingcities/atlanta.htm (November 2003). |

| 17. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. |

| 18. | Danny Solomon, interview by author, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 19 April 2005, and 22 April 2005. |

| 19. | Williams, Hard Labor, 18. |

| 20. | Emmanuel Killen, unrecorded interview by author, Atlanta, GA, 10 October 2003. |

| 21. | Atlanta Labor Pool Worker's Union, Atlanta's Hardest Working People: A Report on Day Labor Pools in Metro Atlanta, (Atlanta: Atlanta Labor Pool Workers' Union, n.d., 1997). |

| 22. | Chirag Mehta et al., Workplace Safety in Atlanta's Construction Industry: Institutional Failure in Temporary Staffing Arrangements (Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Urban Economic Development, June 2003), iii. |

| 23. | Ibid., iii, iv. |

| 24. | Created in March 2003 under the Department of Homeland Security, the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement office (ICE) is currently in charge of immigration enforcement duties once managed by the INS. |

| 25. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. |

| 26. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. |

| 27. | José Fuentes [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 29 July 2003. |

| 28. | Carlos Marín [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 29 July 2003. |

| 29. | Tomás Alcántara [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. |

| 30. | Javier López [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 8 August 2003. |

| 31. | Manuel Guzmán [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 6 August 2003. |

| 32. | Mario Canel [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. |

| 33. | Guillermo Hernández [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Eva Villafañe, tape recording, Canton, GA, 12 August 2003. |

| 34. | Rick Badie, "Economic Downturn: Day Laborers Often Wait in Vain," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 29 April 2001, J1. |

| 35. | Here I draw from two sources that discuss the ways in which perceptions and stereotypes about "inner city" residents, particularly African American men, closed employment avenues. Both studies rely in part on data gathered in Atlanta. See Philip Moss and Chris Tilly, Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001) and Alice O'Connor, Chris Tilly, and Lawrence D. Bobo, Urban Inequality: Evidence from Four Cities (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001). |

| 36. | For a discussion of the ways in which African American construction contractors in Atlanta selected Latino workers over African American workers, see Cameron Lippard, "'Taking Care of Business': The Hiring Practices of African American Entrepreneurs in the Construction Industry" (master's thesis, Georgia State University, 2003). |

| 37. | Statistical and numerical data in this paragraph can be found in these sources: Suzanne M. Marsh and Larry A. Layne, Fatal Injuries to Civilian Workers in the United States, 1980-1995 (Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Health, 2001); Judith T. Anderson, Katherine L. Hunting, and Laura S. Welch, "Injury and Employment Patterns Among Hispanic Construction Workers," Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 42, no. 2, February 2000: 176-186; Stephen Greenhouse, "Hispanic Workers Die at Higher Rate: More Likely Than Others to Do the Dangerous, Low-End Jobs," New York Times, 16 September 2001. |

| 38. | Hugo Sánchez [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Duluth, GA, 31 July 2003. |

| 39. | Samuel Delgado [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, Atlanta, GA, 1 August 2003. Additional words by Samuel Delgado in this chapter are from this 1 August 2003 interview. |

| 40. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. |

| 41. | Delfino Lara [pseud.], interview by author, interpreted by Sarah Johnson, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 1 August 2003. |

| 42. | Abel Valenzuela Jr. et al., On the Corner: Day Labor in the United States, Working Paper of the Center for the Study of Urban Poverty at the University of California at Los Angeles, January 2006. https://cued.uic.edu/wp-content/uploads/onthecorner_daylaborinUS_39p_2006.pdf (25 February 2006), ii. |

| 43. | Ibid., 12, 13. |

| 44. | Ibid., 12. |

| 45. | Jorge E. Simmonds-Diaz, "Environmental and Occupational Health Survey of a Hispanic Work Group in Atlanta" (master's thesis, Emory University, 1993), 17. |

| 46. | Robert D. Bullard and E. Kiki Thomas, "Atlanta: Mecca of the Southeast," in In Search of the New South: The Black Urban Experience in the 1970s and 1980s, ed. Robert D. Bullard (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989), 83. |

| 47. | This statement is based on analysis of metropolitan development in Larry Keating's Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001) and Charles Rutheiser's Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (London: Verso, 1996). |

| 48. | Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, The Breaking of the American Social Compact (New York: New Press, 1997), 278. |

| 49. | Daniel Rothenberg, With These Hands: The Hidden World of Migrant Farmworkers Today (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 217. |

| 50. | Studs Terkel, Working: People Talking about What They Do All Day and How They Feel about What They Do(New York: Random House, 1974), xiii. |

| 51. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Marietta, GA, 21 April 2004. |

| 52. | Day Laborer [anonymous], interview by author, tape recording, Atlanta, GA, 22 April 2004. |