Overview

Speaking at Emory University on April 16, 2007, Prof. Sanchez surveys recent Latino immigration into the US South. He urges the study of contemporary immigrant rights in light of African American historical experience. Sanchez takes note of ongoing research about Latinos' participation in the rebuilding of New Orleans and outlines a multi-year project based at the University of Southern California that will explore African American and Latino relations in several areas of the US, including the South.

Latinos, the American South, and the Future of US Race Relations:

Part 2: Sanchez explores the impact of Mexican immigration on construction work in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina

Part 3: Sanchez explores how the US South became the primary point of destination for Latin American immigrants in the 1990s

Part 4: Sanchez explores how a century-old history of transnational Latino labor networks asserted itself anew following Katrina

Part 5: Sanchez looks to meat and poultry processing industries to note the high rate of Latino migration beyond urban spaces

Part 6: Sanchez describes a project at USC that will explore changing race relations in the US South and Southwest

About George Sanchez

George Sanchez is Professor of History and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945 (Oxford University Press, 1993), co-editor of Los Angeles and the Future of Urban Cultures (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), and recently published "'What’s Good for Boyle Heights is Good for the Jews': Creating Multiracialism on the Eastside During the 1950s," American Quarterly 56, no. 3 (September 2004). He is Past President of the American Studies Association (2001-2002), and is one of the co-editors of the book series, American Crossroads: New Works in Ethnic Studies, from the University of California Press. He currently serves as Director of the Center for Diversity and Democracy at USC. He works on both historical and contemporary topics of race, gender, ethnicity, labor, and immigration, and is currently writing a historical study of the ethnic interaction of Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans, African Americans, and Jews in the Boyle Heights area of East Los Angeles, California in the twentieth century. He is also co-editing, with Amy Koritz of Tulane University, Civic Engagement in the Wake of Katrina, to be published by University of Michigan Press in 2008.

Professor Sanchez's lecture at Emory University was sponsored by the Latin American and Caribberan Studies Program, the Institute for Comparative and International Studies, the Hightower Family Fund, and the Office of the Provost.

Text Version

First, I want to thank Professor Mary Odem, Provost Earl Lewis, and the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program for this invitation to speak to you here at Emory University. I hope that this visit starts a larger dialogue between our two campuses regarding the future of Latino-African American relationships in the US South. At this past January's conference of the American Historical Association in Atlanta, I had the pleasure of reconnecting with Mary Odem on a panel on Latinos in the US South, and my former Michigan colleague Earl Lewis joined in our conversation to examine the changing demographics of Atlanta and the South more generally. At USC, our new department of American Studies and Ethnicity, and specifically our new research institute, the Center for Diversity and Democracy, has decided to take up the issue of African American-Latino conflict and cooperation as our first collective multiyear research project. We have decided to spend at least one year looking specifically at the US South, and put this region's history, politics, culture, and contemporary situation in dialogue with that from around the country. In addition, I have recently been working on an edited book on community engagement in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, so my own scholarly work is beginning to move out of Los Angeles to this region beginning in Louisiana. I look forward to your comments and questions regarding this work and this presentation—because I am just beginning to branch out from a California focus!

A year ago, on Wednesday March 29th, 2006, two thousand Latinos marched to the state capitol in Nashville, Tennessee to protest the role of Senator Bill Frist, the then-US Senate majority leader, in trying to criminalize the undocumented in the United States in pending legislation before Congress, as well as protesting the abolition of a driving certificate program for undocumented workers sponsored by that state. For most of these Southern protestors, this was the first time they had organized or participated in a protest march. Other more modest protests occurred throughout the South, with 5,000 marching in Charlotte, North Carolina and 150 marching in Birmingham, Alabama. The larger community in Atlanta initially decided not to march last year but instead to call for a boycott from work and shopping to show their economic impact, but were unable to stop the Georgia legislature from passing a bill to curtail government benefits to illegal immigrants. Organizers in Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina held rallies in April 2006 to back this growing immigrant rights movement. In South Carolina, this effort was led by a two-year-old immigrant rights group named the Coalition for New South Carolinians. While the size of these protests was dwarfed by the half million that marched in Los Angeles on March 25th or the 200,000 that marched in Chicago, the very public act of protest itself was critical in these new southern communities without a long history and with many in undocumented status.1Richard Fausset, "Nervously, Latinos Protest in the South," Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2006, A16.

Indeed, as the movement to protect immigrant rights began to grow throughout the South, more activists who had long worked in African American civil rights campaigns began to participate and lead efforts. One such person was Jim Embry from the Sustainable Communities Network in Lexington, Kentucky, who has been an activist in that community for over 40 years, beginning as a CORE civil rights activist in 1960. On April 10, 2006, he spoke in front of the Lexington County courthouse before a crowd of 7,000 people, and the connections he saw to past struggles:

This Immigrants' Rights Rally here in Lexington is also in a historic place because directly behind this stage is the old courthouse... the building with the clock, where only 150 years ago this area around the courthouse was an auction block where African people, said by whites to be less than human and denied rights, were bought and sold into slavery. During the years of slavery African people would try to escape slavery by crossing the Ohio River to the North. The Ohio River was the border between the free states of the north and slavery states of the south. Even after crossing the Ohio River many of these African people could not produce their freedom papers—or let's say that they were undocumented—and thus, they were rounded up as illegals in the North, were chained and brought back to this very spot in Lexington—whipped and beaten—and often were then sold back into slavery and deported to the deeper South where the conditions of slavery were much more harsh and cruel.

He went on to connect this history to that he saw in the contemporary period:

Those conditions during enslavement of African people—people risking their lives by escaping slavery in the South on the underground railroad and crossing the Ohio River—are quite similar to Mexican people and others today risking their lives by crossing the Rio Grande and the desert on a similar underground railroad seeking a better life for their families. Still today without your "freedom papers" or being undocumented, immigrants can be rounded up and sent back across a similar border and river separating North from South. The denial of freedom, respect and full citizenship rights to African people years ago was immoral and unjust and today the denial of respect and citizenship rights to immigrants from Mexico and around the world is also immoral and unjust. Because of our unique and continuous struggle for freedom, rights and equality, African-Americans should be very supportive and in the forefront of the struggles by other people in this country and around the world who are denied full equality, respect and rights as citizens of this earth.2Jim Embry, "Rivers That We Cross . . . Our New Wave of Immigrants from the South," Latino Studies 4 (2006): 448–449.

While Embry looked for ways of connecting the two histories and time periods, others, of course, looked for differences between the two experiences and histories.

Meanwhile in New Orleans, workers from Mexico were more likely to be busy working difficult jobs rather than organizing protests last year. The impact of Mexican immigration has been most keenly felt after Hurricane Katrina in the demolition and reconstruction efforts underway since the disaster struck in August 2005. According to the 2004 update to the US Census, the city of New Orleans had only 1,900 Mexicans, with an overall Hispanic population of just three percent, mostly made up of Hondurans with many having middle class status. John Logan, a Brown University demographer, estimated in April 2006 that "there must be 10,000 to 20,000 immigrant workers in the region by now, and the number is going to grow."3Sam Quinones, "Migrants Find a Gold Rush in New Orleans," Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2006, A10. Latino workers have gutted, roofed and painted houses, installed drywalls, and hauled away garbage, debris, and downed trees. They have spent their days putting blue tarps on roofs and installed trailers to house returning evacuees. Their pay for much of this work has been coming from FEMA subcontractors, and most of these say that they could use thousands more to move along the efforts at rebuilding. In a city desperate to move forward and prepare quickly for the coming hurricane season, the availability of workers willing to put up with strained working and living conditions have allowed for much reconstruction to actually take place.

With 140,000 homes destroyed or damaged by Hurricane Katrina, 60 percent of its residents relocated to other cities and towns, and the remaining residents determined to rebuild, Latinos, specifically Mexican workers, both legal and illegal, and both already residing in other part of the US and residing in Mexico, began coming in droves to New Orleans by mid-September 2005 and have continued ever since. Given the lack of adequate housing in the city, some of these workers reported sleeping in a park for over a month and showering with hoses each day. Others have slept in hotel rooms or friend's apartments, often six or seven in a sleeping quarter planned for one or two. A few churches in the region have reported opening their doors to these newcomers, sleeping in curtained-off alcoves. Some of these churches and other organizations have begun to sponsor Mexican films on Friday nights, medical clinics on the weekends, even setting up soccer nets nearby. Tulane University in New Orleans began publishing their bulletin of available jobs for the first time in both English and Spanish.

Yet, many of these workers, along with other Latinos that had already made their home New Orleans before Katrina, have reported increased tension and anti-immigrant sentiment growing. Azucena Diaz, disc jockey for Radio Tropical Caliente, one of the two Spanish language stations in town, and a Mexican-born US citizen who moved here from Pomona, California five years ago, reports that she has seen Latinos, including her own husband, insulted on the streets of New Orleans recently. Police in Metairie, Louisiana have reportedly run off immigrants looking for day labor, while Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers (ICE has replaced INS under the Department of Homeland Security) have arrested hundreds of men gathered at popular gathering spots for day laborers. Some African Americans see recent Latino immigrants as usurpers of jobs now that wages have risen, while black workers have been displaced. And in a widely reported incident at an October 2005 forum with business leaders, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin asked those gathered, "How do I make sure New Orleans is not overrun with Mexican workers?" With anti-immigrant sentiment rising across the nation, and the US Congress and radio talk show hosts continually debating what is perceived as an illegal alien crisis, the past two years has proven to be ripe for interracial tensions amidst pressure to protect national borders while rebuilding critical internal infrastructure.

What has happened in New Orleans is, in many ways, no different than what has happened across the nation, particularly in the last twenty years across the American South. The big difference has been the rapidity of change brought about by the suddenness of the Katrina disaster and the huge void left in the labor market due to the loss of sixty percent of the pre-Katrina residents of New Orleans. That demographic shift is also what makes the "browning" of New Orleans so visible, after decades of rather unnoticed migrant streams and largely invisible immigrant communities. What is key, I believe, in the current moment is to realize that despite the rapidity of change and transformation, the larger pattern of Mexican in-migration has occurred throughout the American South, and has finally arrived in New Orleans post-Katrina.

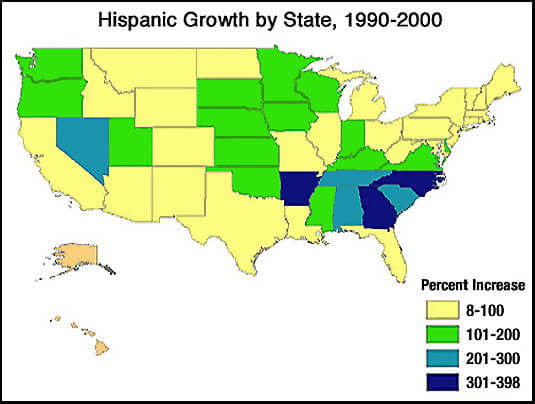

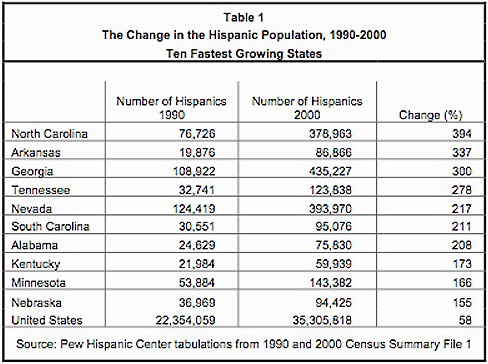

The 2000 census reported that seventy-five percent of the Mexican-descent people of the United States lived in the five states of the American Southwest, Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. But the most rapid recent growth of the Mexican population, however, has taken place outside this traditional area of Mexican settlement. The Mexican population grew most rapidly in the American South during the 1990s, where the number of Mexicans tripled, the Northeast, where it almost tripled, the Mountain West, where it more than doubled, and the Midwest, where it nearly doubled. A greater percentage of Mexicans in the nation now live in the southern states of the United States (excluding Texas), slightly more than seven percent, than in the Western region of Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming, where no more than 6 percent live. The Mexican population of North Carolina grew by close to 400% during the 1990s, while the increase of Latinos in Georgia was so rapid that their share of the state's total population went from one percent to five percent in one decade. Of course, the largest national-level news from the updates of the census in the past few years has been that the total Latino population, over sixty percent of which is Mexican-origin, now totals more than the African American population in the United States.

Part of the reason for this shift in the Latino population is the dramatic shift in points of destination among newcomers from Mexico throughout the 1990s and in the first years of this decade. Ironically, one reason for this shift was greater enforcement of immigration laws on the Mexican/California border and in interior sections of California. The percentage of new legal and illegal Mexicans arriving in California dropped ten percentage points during the 1990s, from an all-time high of fifty-seven percent in the year 1990. Many of those newcomers ventured instead to points in the American South. Moreover, California's deep recession in the early 1990s and its anti-immigrant legislation and ballot initiatives also played a role in redirecting the migrant stream towards the American South. Another way of looking at this shift is that California schools are now dominated by the children of the earlier immigrant stream from the 1980s, including both US citizens by birth and those who arrived as children in the United States. Evidence of this phenomena are the huge numbers of young people who boycotted middle school and high school classes last year to speak out for the dangers to their immigrant parents. In the South, however, the migrant stream is newer, therefore young working adults dominate most communities, with children, if present at all, usually of much younger ages. This relative mobility without fully planted families made Mexican immigrants in the South more likely to move quickly when economic opportunities in New Orleans beckoned.

Indeed, the US South has now benefited for decades through patterns of labor recruitment from Latin America that have created networks of the ablest workers of this hemisphere willing to move far to take advantage of economic opportunity wherever it exists. What was displayed in the wake of Katrina is the strength and adaptability of these labor networks, stretching across regions of the United States, and deep into Mexican and Central American villages and towns to the south. Just a few pre-Katrina Latino neighborhoods in Louisiana and neighboring states, made up of pioneer migrants who had ventured to the area to take advantage of work in construction, forestry, and oil production, started this shift in the wake of the destruction by the hurricane.

Mexico only first appeared among the top-five sending nations to Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama in the census year 2000. While eight percent of the foreign born population of Louisiana came from Mexico in the year 2000, almost twenty-eight percent of the foreign born in those two neighboring states came from Mexico in that same year. So rather than think that this migration from Mexico to New Orleans is only a result of the post-Katrina period, migration of Mexicans had already important roots in the region. In the early 1990s, Mexican migrants came to Louisiana to work in shipbuilding and fabrication yards in southern coastal parts of the state, and in neighboring states were working in casino construction and in forestry. In several nearby parishes in Louisiana, migrants from Mexico had established important roles in the oil production industries. Already pre-Katrina, two local radio stations in New Orleans broadcast in Spanish only, and almost all Catholic churches conducted at least some of their services in Spanish. Several cultural associations had already formed to promote the celebration of Cinco de Mayo and other events in the decade before Katrina.

The presence of these communities, however, in the long run created the beginnings of networks that would draw other Latinos from the rest of the South, the nation, and eventually from Mexico itself to aid in reconstruction of the region after the initial shock of Katrina dissipated. The hotels were among the first to hire, just days after Katrina hit, as they prepared for housing aid workers coming in. Most of their regular employees had fled the disaster zone, and many temporary workers could be found gutting rooms at the local Marriott and Holiday Inn hotels. Some of these workers would then move on to employment helping small businesses or homeowners do preliminary work to repair their places of residence or livelihood, especially for those not willing to wait for FEMA's now notorious slow process of assistance. Some found work "house leveling"— lifting houses sunk in marshy post-Katrina soil using hydraulic jacks and propping them on stilts, bricks, or concrete supports. These methods of building support and repair, while seemingly primitive and experimental in the United States, are familiar and used widely in areas of Mexico and Latin American with similar climates and prone to be in the path of summer hurricanes. In other words, they brought often unacknowledged skills and experience in construction to the tasks needed in New Orleans.

As work opportunities became more routinized, demand expanded, and wages rose to $15 to $17 dollars an hour, labor agencies and contractors began to fully exploit the networks in these immigrant communities to draw more newcomers to New Orleans to do this labor. In many cases, labor networks that had previously been utilized to draw hotel workers or oil workers to Louisiana were now utilized for recruitment of demolition and construction crews. New day labor pickup sites developed in a city that had virtually no experience with this form of labor recruitment sites before. These sorts of informal hiring sites, of course, exist all over southern California, and now are national phenomena which often raise the anger of local residents while others take advantage of workers willing to put in a hard day's work for decent pay from contractors and individual homeowners alike. Many of the workers who came to New Orleans in October and November 2005 came from other sites in the metropolitan South like Nashville, Atlanta, and Charlotte to take advantage of the higher wages and more critical demand for laborers in New Orleans. Individual building contractors in New Orleans, who lost most of their workers in the wake of the hurricane, hired workers quickly, and called on these first workers to contact other family members or acquaintances to come from other places to join them. Some, like Perry Custer, who owns a small construction firm in New Orleans trying to rebuild six apartment buildings and office complexes, sent foremen to recruit extra labor as far away as Atlanta and Houston. Former Latino workers that had been firmly rooted and well-known in New Orleans construction circles have left their regular jobs to become labor brokers, supplying newcomers to contractors while providing housing and meals to workers for a cut of their wages.

This expansion of transnational labor networks throughout a region is nothing new for Mexican workers, of course. Indeed, many of these networks spread deep into the villages of central Mexico and throughout Central America, and have been critical in drawing workers and families north across the border since the early twentieth century. I documented much of that networking in my first book concerning Mexican immigration to Los Angeles in the first four decades of the twentieth century. During the Bracero Program from 1942 to 1964, these networks were institutionalized by government contracts sponsored by the United States which regularly drew workers from the interior of Mexico to the north, particularly to California, the Pacific Northwest, and the Midwest. When the Bracero Program was discontinued in 1964, many of these networks continued to produce transnational movement, now drawing those with and without documents to the north as Mexico was put under a national quota for the very first time in 1965. More recently, other networks of employment, such as those drawing indigeneous workers from Puebla to work the restaurants, cleaning crews and construction jobs in New York City, developed up and down the East Coast. Usually unacknowledged by political discussions that focus on individuals crossing the border to seek economic opportunity, intricate and highly developed networks exist from all the major population centers throughout Mexico and specific locations in the United States.

One of the most striking aspects of recent migration to the US South has been the extraordinary high rate of Latino migration to areas outside of metropolitan districts. While you have clearly seen the increase in Mexicans living in Atlanta, as I have observed in the city of New Orleans, over the past fifteen years the greatest increases have taken place in rural areas of the South, reinvigorating deteriorating populations and being drawn there by extensive structural economic change. In the 1990s, Latino nonmetropolitan growth was over seventy percent, which exceeded their metropolitan growth rate of 60 percent during the decade, and accounted for over twenty-five percent of the total growth of rural areas in the United States during the 1990s. But this migration was also highly concentrated, as over a third of the 3.2 million rural Latinos lived in just 109 of all 2,300 nonmetropolitan counties.

According to William Kandel and Emilio Parrado, the development of the poultry industry across the region was a key economic factor in the enormous impact Latino migration had on rural Southern communities. In an important article, they chronicle the growing tension in two such communities, Accomack County, Virginia and Duplin County, North Carolina.4William Kandel and Emilio A. Parrado, "Hispanics in the American South and the Transformation of the Poultry Industry," in Daniel D. Arreola, ed. Hispanic Places, Latino Spaces: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 255–276. With heavy recruitment by Tyson, Perdue, and other meat processing plants, both these counties rapidly moved from a biracial white-black population to an increasingly multiethnic population with a significant Latino population. Mexicans represented over 65 percent of this Latino population in both counties, with Guatemalans and Hondurans making up most of the rest. The part of the Latino population that the census did not capture was the substantial seasonal agricultural migrant workers who passed through both counties. Kandel and Parrado conclude that the rapid influx of Latino workers did not necessarily reflect displacement of native white or black workers, since unemployment actually was halved in both counties during their period of study, and were much lower than the nationwide nonmetropolitan average.

They also found, however, that the patterns of new migration strained local social services, especially educational services and housing, since these newcomers overwhelming rented and had young children that did not speak English attending primary grades. Similar to what I saw unfolding in New Orleans, gender ratios for Latinos were significantly different than for the general population. In Duplin County, for example, the gender ratio for whites was ninety-five men per one-hundred women, eighty-four for blacks, but 156 for Latinos. This stark difference, especially between Latinos and African Americans, affects the very nature of their interaction in all sorts of ways in both rural and urban spaces.

For many in these southern communities accustomed to longstanding neighborhoods with rich histories and deep organizational ties to this space, it may appear as if these Mexican and other Latino newcomers are unlikely to remain for long and should not be considered real "residents" of the city until it is clear that they are here for more than a temporary sojourn. The long term viability of these neighborhoods is necessarily tentative, but there are signs that I would use, based on longstanding patterns in Latino migration throughout the twentieth century, that we might use to assess whether we are witnessing long term settlement patterns that will reshape the basic contours of southern society.

A more equal sex-ratio within the migrant community is a strong sign of permanent settlement among newcomers, as men bring wives and families north from Mexico or from elsewhere in the United States, or Latino men begin to intermarry with local women. Eventually more single women migrate to the region to be involved in various economic opportunities, and family life begins to be centered in more permanent settlements throughout the region. Starting a family in any location, be it 1920s Los Angeles or twenty-first century New Orleans, is a clear indication that those individuals intend to reside permanently in that location. Moreover, rooting a family strengthens the power of the local community as a whole, with more organizations dedicated to community improvement, raising children, advancing education, and becoming integrated into the local cultural scene. It creates new opportunities for entrepreneurial activity, as small shopkeepers begin to meet the needs of a growing community and a range of family desires. While the initial male migration may immediately lead to a plethora of new restaurants to serve clientele, more established settlement usually involves grocery stores, entertainment venues for the whole family, and eventually enrollment in all levels of the local public schools.

It also appears that we have been witnessing a long-term structural transformation of local economies in both rural and urban regions of the South, and this indicates that this migration is clearly a permanent feature of the labor market scene and will usually translate into permanent settlement. In New Orleans, the huge size of the task of reconstruction was a strong indicator of the likelihood of long term settlement. Most contractors seem to have work that they predict will last at least two to five years from this date, and many desired rebuilding projects are still in the planning stages. In other words, the demands for these workers is likely to last for quite some time to come, as it becomes clear that reconstruction will take an enormously lengthy period of time. As has happened elsewhere, then, what is likely to occur is that the longer individual workers find themselves in New Orleans the more likely they are to decide to remain here. These workers, in turn, will broaden the labor networks that bring more of their countrymen here, as long as rebuilding jobs continue to exist. Moreover, as other New Orleanians return to the city, growing demands for cleaning crews, fastfood employees, etc., will begin to be prioritized, as slowly a wider economic marketplace reemerges.

It will be critical, in this environment, to insure that labor cooperation, rather than competition, dominates the landscape, since this transition is likely to fray nerves based on expectations of progress, identity, nationality, race, and heritage. And enforcement of anti-discrimination laws is critical in the new environment, be it residential discrimination that might be aimed at immigrants by nativist landlords or employment discrimination against native African Americans by racist employers who prefer immigrant labor. Historically, of course, there are many successful examples of transition to draw from, such as the peaceful return of Japanese American internees to Little Tokyo in Los Angeles after their former businesses and residences had been occupied by migrating African Americans from the South to meet the labor needs of World War II. What has been key in the past is the establishment of grassroots organizations dedicated to proactively working towards racial cooperation and reconciliation, willing to expose examples of persistent discrimination and prosecute offenders across all racial lines.

Compared to other regions in the country, the US South seems to be one of the strongest places for these sorts of grassroots organizations, largely due to the continued legacy of civil rights organizations from the movement for African American liberation. Compared to Los Angeles or New York, two cities that I know well, the civil rights legacy continues to be strong and is more adaptable to the needs and interests of recent immigrant communities. I have been particularly impressed with the role of the Southern Poverty Law Center, based in Montgomery, Alabama, in their advocacy for immigrant rights and their willingness to translate their considerable expertise to improve the fate of these Latino newcomers. Other national organizations, like the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), has opened up branches in the South and often coordinate with traditional African American civil rights organizations to come together in coalition-building. In many ways, these coalitions pick up where the Poor People's Movement, started by Martin Luther King Jr. just before his death, left off; organizing across racial groups to combat poverty and discrimination.

The demographic and social transformations we are witnessing have the potential for shifting major discussion of US society and culture. In my recent talks at conferences on the US West, for example, I am consistently talking about the bifurcation of that region into two Wests, one made up of the traditional areas of Mexican settlement now reinvigorated by recent migration—including California, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and increasingly Nevada—and the interior, mountain West, along with the Pacific Northwest, where Anglo Americans are migrating to in order to avoid huge urban growth and often Latino migration. The Southwest increasingly is more compatible to the US South than the rest of the West, with racial diversity, Sunbelt economics, and widespread migration, now couched largely in the language of globalization.

Despite all these obvious changes and the new levels of interaction existing in these regions, my department of American Studies and Ethnicity at USC has chosen to systematically explore the changing nature of African American-Latino interaction across various regions and interdisciplinary topics over the next five years. We were initially prompted to do this because of increasing tensions between the two groups in prisons and schools in southern California, as well as by a series of violent incidents in various neighborhoods in the region. In December 2006, in the neglected Harbor Gateway area of the city of Los Angeles, a fourteen-year-old African American girl was brutally murdered by what authorities called a racially motivated hate crime carried out by Latino teenagers who were members of a local Latino gang. In response, members of both racial groups marched singing "We Shall Overcome," while a Latina law professor writes an editorial blaming the violence on the historic racism against African peoples from the cultures of Latin America that in the US translates into "Latino ethnic cleansing of African Americans from multiracial neighborhoods." Coupled with the reality that these two groups now form over one-quarter of the entire US population, we believe it is time for concerted intellectual effort to move along dialogue about the interaction of these two groups which seems critical for the future of American society.

Through our new Center for Diversity and Democracy at USC, we have launched a "Black-Brown" Initiative that takes advantage of our own intellectual and racial diversity, our new faculty and graduate student interests, and our commitment to racial equity. From historians like myself, Maria Elena Martinez, Lon Kurashige, William Deverell, and Robin D.G. Kelley, to social scientists like Ruthie Gilmore, Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Leland Saito, Manuel Pastor, Laura Pulido and Herman Gray, to humanists like Fred Moten, Teresa McKenna, Tara McPherson, Judith Jackson Fossett, and Josh Kun, we are all interested in working collaboratively to advance a national conversation regarding African American and Latino conflict and cooperation. While we encourage other campuses must find their own particular strengths and challenges and move forward, unafraid to take on difficult issues facing our communities, I would like to find university partners to join us in this particular quest for new answers, new theories to understand and interpret these challenges.

Our plan right now is to begin with a year that focuses on Los Angeles, then follow that with a year concentrating on the US South. This is when I hope we might collaborate with a group of interdisciplinary scholars from Emory University that would be interested in exchanging ideas, collaborating on research, and promoting advanced education for PhD students and undergraduates to explore interethnic issues. At USC, we plan to continue our multiyear effort with a year focused on race in Latin America, then a year on the New York metropolitan area. Finally we will end with a year dedicated to theory and practice in interracial issues, focused on advanced scholarly approaches to the study of relations between African Americans and Latinos. Certain themes, such as music and culture, politics and community organization, will stretch across all five years of the project. We are finalizing plans for a book series that will produce an edited volume each year, and attempt to draw leading scholars focused on each geographic and topical area to contribute to advancing this discussion.

In this working and still developing plan, I am reminded of one of the first studies of a community of Latinos in the American South, Leon Fink's wonderful ethnography of "The Maya of Morganton" which traced the sense of solidarity that developed among a group of Guatamalan chicken plant workers who found themselves employed and residing at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina. Fink's study traces the evolution of this important community, particularly their eventual willingness to fight for better working conditions through union activity, even though most of them were in this country illegally. In his very last paragraph, he puts out a similar hope of reaching across national and racial lines by all in the community to achieve common goals:

There are many ways . . . whereby the nation's institutions might better accommodate their hardest-working "hands." Workers themselves, to be sure, are at the heart of this struggle, but to succeed they will need to join with members of an aroused, and established, citizenry. It is common to talk about immigrants and the American Dream as if the latter were something that US citizens already possess and others have to strive for. Yet, when it comes to the prospect for American democracy at the dawn of a new century, the welfare of new immigrant labor forces will likely tell us as much about our own dreams as about theirs.5Leon Fink, The Maya of Morganton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 199–200.

Nowhere is that analysis more accurate, I believe, than here in the future of the American South, that we all hold in our hands. Thank you, once again, for your invitation, and I welcome all questions and comments.

Recommended Resources

Text

Fink, Leon. The Maya of Morganton. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Goldfield, David. "Unmelting the Ethnic South: Changing Boundaries of Race and Ethnicity in the Modern South," in Craig S. Pascoe, Karen Trahan Leathem and Andy Ambrose, eds. The American South in the Twentieth Century, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005, 19–38.

Kandel, William and Emilio A. Parrado. "Hispanics in the American South and the Transformation of the Poultry Industry" in Daniel D. Arreola ed. Hispanic Places, Latino Spaces: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004, 255–276.

Kochhar, Rakesh, Roberto Suro and Sonya Tafoya. "The New Latino South: The Context and Consequences of Rapid Population Growth," Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center, 26 July 2005. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2005/06/14/unauthorized-migrants/.

Sanchez, George. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

———. "'Y tu que?': Latino History in the New Millenium" in Marcelo Suarez-Orozco and Mariela Paez, eds. Latinos!: Remaking America, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002, 45–58.

Web

Harriet Tubman Resource Centre on the African Diaspora

http://www.yorku.ca/nhp/intro.htm.

Hurricane Digital Memory Bank

Collecting and preserving the stories of Rita and Katrina.

http://hurricanearchive.org.

Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota

http://www.ihrc.umn.edu.

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF)

http://www.maldef.org.

Southern Poverty Law Center Immigrant Justice Project

http://www.splcenter.org/legal/ijp.jsp.

Maps and Tables

US Map: Hispanic Growth by State, 1990–2000.

Source: Pew Hispanic Center tabulations from 1990 and 2000 Censuses

From: Rakesh Kochhar, Roberto Suro and Sonya Tafoya.

"The New Latino South: The Context and Consequences of Rapid Population Growth,"

(Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center, 26 July 2005)

http://www.pewhispanic.org/2005/06/14/unauthorized-migrants/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Richard Fausset, "Nervously, Latinos Protest in the South," Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2006, A16. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Jim Embry, "Rivers That We Cross . . . Our New Wave of Immigrants from the South," Latino Studies 4 (2006): 448–449. |

| 3. | Sam Quinones, "Migrants Find a Gold Rush in New Orleans," Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2006, A10. |

| 4. | William Kandel and Emilio A. Parrado, "Hispanics in the American South and the Transformation of the Poultry Industry," in Daniel D. Arreola, ed. Hispanic Places, Latino Spaces: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 255–276. |

| 5. | Leon Fink, The Maya of Morganton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 199–200. |