Overview

Scott Matthews examines the documentary work John Cohen (August 2, 1932–September 16, 2019) produced in eastern Kentucky from the late 1950s into the 1960s, particularly the image he created of singer-musician Roscoe Halcomb, who is prominently featured in Cohen's 1963 film The High Lonesome Sound (made in collaboration with Joel Agee). Cohen, a musician, photographer, and member of the group The New Lost City Ramblers, met Halcomb in Eastern Kentucky in 1959, when the area was in the grip of an economic depression. Through sound recordings, photography and film, Cohen spread Halcomb's music and image throughout the folk revival scene of the early 1960s, making him an iconic embodiment of artistic authenticity based in the grinding poverty of Appalachia (and turning his recognized name to Roscoe Holcomb along the way). The article shows how Cohen's representation of the depressed conditions that shaped Halcomb's existence contributed to the power of Halcomb's mythic image during this time. Matthews also explores the differences between the two men's views on the relationship of art, work, poverty, and survival. Based upon several extended interviews with John Cohen as well as other historical materials, the article examines Cohen's friendship with Halcomb and his relationship to Halcomb's personal life and musical career, with special attention to the production and reception of The High Lonesome Sound.

"John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky" is part of the 2008 Southern Spaces series "Space, Place, and Appalachia," a collection of publications exploring Appalachian geographies through multimedia presentations.

Preface

On a muggy Sunday afternoon in June of 1959, John Cohen wandered the winding mountain roads of eastern Kentucky searching for old-time musicians. Neon, Bulan, Vicco, Viper, Daisy, Defiance — tiny coal and timber towns with sonorous names popped up around each bend before giving way to the Cumberland Mountains. Cohen had come to Kentucky from New York City to find songs about "hard times" that would fill out the repertoire of his old-time music group, the New Lost City Ramblers. "In order to experience an economic depression firsthand, I visited eastern Kentucky and made photos and field recordings for six weeks in 1959," he recalled.1Ronald Cohen, ed. "Wasn't That a Time!": Firsthand Accounts of the Folk Music Revival(Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995): 38. "The United States was quite prosperous at that point, but east Kentucky wasn't and I had heard about that. . . . And I said, 'Maybe I can find some music about the depression, experience the depression, and understand it more and maybe photograph it, maybe record music.'"2John Cohen, interview by the author, Putnam Valley, New York, September 1-2, 2006. Hereafter cited as Cohen Interview.

|  |

| Map used by Cohen to navigate Kentucky, 1959. | John Cohen, Two girls walking, Vicco, KY, 1959. |

Later in the day, Cohen began to wonder whether his trip was in vain. He had exhausted every name on his search list of banjo players and he had no desire to return to the hot boarding house room along the railroad tracks of Hazard. Earlier, he had visited an eighty-five-year-old fiddler, Wade Woods, but Woods could barely play anymore. On a whim, Cohen took the first dirt road that led off the main highway to see what or who might turn up. Turning off the hardtop, he crossed over a little bridge and stream and entered a lumber-mill village called Daisy. He approached a couple of small houses and, at the first one, asked some children standing out front, "Any banjo players around here?"

"Over there in that house," they replied.

Cohen pulled up and recognized a young man named Odabe Halcomb he had recorded the night before at a nearby roadhouse.

"What are you doing here?" Halcomb asked, surprised to see this outsider on his doorstep.

"Well, I'm looking for music," Cohen said.

Halcomb turned to his adopted aunt, and Cohen asked her to play a banjo tune. Mary Jane Halcomb played a couple of songs including, "Charles Guiteau," about assassin of President James A. Garfield. Suddenly she announced, "Here comes Rossie!"

|

| John Cohen, Roscoe Holcomb, Daisy, KY, 1959. |

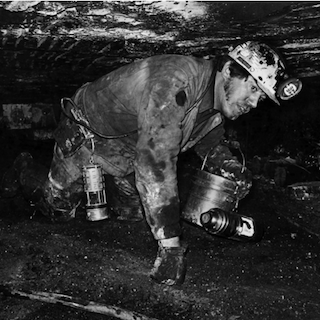

A wiry and weathered man, aged forty-seven, Roscoe Halcomb walked toward the house.3Halcomb's name appears as "Roscoe Holcomb" on the Folkways records he recorded for John Cohen. I learned of another spelling of his name while visiting Halcomb's friends and relatives in his native Perry County, Kentucky during the summer of 2006. His nephew took me to his gravesite where I saw his name spelled "Rosco Halcomb" on his tombstone. In his letters to John Cohen, Halcomb would also spell his name "Roscoe" or "Rascal." The variety of spellings is due in part to Halcomb's handwriting. The spelling of his correct last nam — Halcomb —is not in question. The Halcomb name is prevalent in that part of Kentucky. In the 1920 census, when he would have been seven years old, he is listed as Rossie Halcomb. Cohen kept his last name as Holcomb for presentation purposes, believing that Roscoe Holcomb looked and sounded better than Roscoe Halcomb. Throughout this essay, I will refer to Halcomb in the way that he most often addressed his letters to Cohen: Roscoe Halcomb. A manual laborer and former miner, Halcomb lived at the very end of the hollow in Daisy. After some cursory introductions, Halcomb played a song for Cohen called "Across the Rocky Mountain." "My hair stood up on end," Cohen later remembered. "I couldn't tell whether I was hearing something ancient, like a Gregorian Chant, or something very contemporary and avant-garde." The combination of pulse-like rhythm, coupled with the high, tight singing, and the insistent droning notes of the guitar had its effect. "It was the most moving, touching, dynamic, powerful song I'd ever experienced . . . not the song itself but they way he sang it was just astounding. And I said, 'Can I come back and hear you some more?'"4Tom Davenport and Barry Dornfeld, Remembering the High Lonesome (2003), film from Folkstreams, http://www.folkstreams.net/film,42; "Transcript to Remembering the High Lonesome," Folkstreams, http://www.folkstreams.net/context,92, 2-3.

Roscoe Halcomb allowed Cohen to visit him at home on a number of occasions to record, photograph, and film him. Cohen produced a remarkable documentary, The High Lonesome Sound, not only of Halcomb and his music, but also of the social, economic, and cultural life of Daisy and Perry County. Cohen's work undermined stereotypes by portraying Appalachian people differently than the typical "hillbilly" caricatures that circulated on television, in movies, cartoons, and popular magazines during the 1950s and 1960s. Cohen countered these images through documentary realism, depicting the diversity and vitality of eastern Kentucky's cultural life while revealing the poverty that an exploitative mining economy created.

Clip from Roscoe Halcomb, "Across the Rocky Mountains," Disc One, Mountain Music of Kentucky CD, Smithsonian Folkways CD 40077.

A sympathetic interpreter, Cohen still controlled the means of representation. He acknowledged that subjective desires and motives dominated the documentarian's objective conceits. Documentary workers revealed and described, but also framed and selected. "Although I had come to Kentucky to document what I heard," Cohen later reflected, "inevitably the undertaking required me to become an editor. I was put in the position of determining . . . how [Roscoe] was presented, and photographed. Like it or not, my task was to shape Roscoe's image. I was uneasy with this situation, but then again, there were few alternatives." Cohen was neither a social scientist diagnosing the causes of poverty, nor a journalist writing or filming an exposé for a national outlet. He arrived before Michael Harrington's The Other America (1962) focused the nation's attention on Appalachia as one pocket of poverty in a nation of affluence and before Harry Caudill published the groundbreaking and controversial book Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1963). Cohen also visited the region eight years before a man named Hobart Ison shot and killed a Canadian filmmaker named Hugh O'Connor as he filmed a coal miner sitting on the porch of the home he rented from Ison in Jeremiah, Kentucky, just down the road from Daisy. Ultimately, Cohen came to observe an economic depression and the music and culture of the Mountain South that possessed his heart and mind.5Michael Harrington, The Other America: Poverty in the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1962); Harry M. Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area (Boston: Little, Brown, 1963); John Cohen liner notes in Roscoe Holcomb: An Untamed Sense of Control (Smithsonian Folkways CD 41044, 2003): 8-9.

Introduction

John Cohen's documentary work strived to produce a humane picture of Appalachia, but it also created a new romantic mythology that depicted Roscoe Halcomb as a visionary folk musician who, according to Cohen (writing in the mid-1960s), represented "a vanishing breed of people who have held onto their traditions despite mass culture."6When I use the word "romantic" or "romanticism" in this essay, I am taking my definition from Michael Lowy and Robert Sayre who argue in Romanticism Against the Tide of Modernity, that "Romanticism represents a critique of modernity, that is, of modern capitalist civilization, in the name of values and ideals drawn from the past (the precapitalist, premodern past)." Romanticism in their view represents a "modern critique of modernity." The implication is that "even as Romantics rebel against modernity, they cannot fail to be profoundly shaped by their time. . . . Far from conveying an outsider's view, far from being a critique rooted in some elsewhere, the Romantic view constitutes modernity's self-criticism." Further, romanticism means "to flee bourgeois society," to leave cities or modern conveniences or jobs behind for the seeming purity of rural areas, trading the modern for the "exotic," "abandoning the centers of capitalist development for some 'elsewhere' that keeps a more primitive past alive in the present." Romanticism also represents an effort to patch together the "modern fragmentation" of folk cultures. The documentary form, whether in writing, photography, film, or sound recording provides a way to preserve aspects and images of folk culture before they disappear. Consequently, documentary expression in the South has, at times, resembled an ethnographic salvage project that tries to give coherence and meaning to a way of life constantly on the brink of extinction. See Michael Lowy and Robert Sayre, translated by Catherine Porter, Romanticism Against the Tide of Modernity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), 17-24. Cohen said his band-mate in the New Lost City Ramblers, Mike Seeger, referred to Halcomb's "outlook" as "Medieval." Mythologizing an Appalachian musician's supposed premodern purity was nothing new.7The creation of Roscoe Halcomb's image provides a perfect example of what historian Benjamin Filene refers to as the "cult of authenticity" surrounding roots musicians during the twentieth century; see Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000). As the title suggests, Filene's book is about how a diverse cross-section of folklorists, musicians, record executives, and other Americans remembered the country's musical past, how they transmitted these memories, and the role they played in American cultural life. Though he does not address Cohen or Halcomb, his chapter on the relationship between Leadbelly and John and Alan Lomax provides an interesting comparison with valuable insights. The Lomaxes, according to Filene, promoted Leadbelly as a symbol of "actual folk," and created a "cult of authenticity" and a "web of criteria for determining what a 'true' folk singer looked and sounded like and a set of assumptions about the importance of being a 'true' folk singer." (49). Though not directly influenced by the Lomaxes, Cohen's own promotion of Halcomb fits into the broader cultural trend identified by Filene. As "isolated cultures became harder to define and locate in industrialized America, the notions of musical purity and primitivism took on enhanced value . . ." (3). One thing that distinguishes Cohen from the Lomaxes is Cohen's independence from any institutional affiliation like the Library of Congress. He always worked as an independent artist or musician and conducted documentary work on his own terms, even though he promoted Halcomb by getting him record deals with Folkways Records, which then circulated his image and music to consumers. Generations of folklorists, song collectors, and writers had portrayed Appalachia as a rural and isolated idyll that preserved and protected the last vestiges of pure Anglo-Saxon culture from corrosive forces of industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. Cohen's descriptions of Halcomb at times evoked similar myths about the Appalachian folk created by writers like Will Wallace Harney and William Goodell Frost in the late nineteenth century, song collectors like Cecil Sharp in the 1910s, and by members of the Popular Front in the 1930s like Charles and Pete Seeger or Woody Guthrie who championed and mythologized another Kentucky balladeer and mining strike organizer named Aunt Molly Jackson. Most importantly, though, Cohen combined elements of these old myths with new insights provided by modern art and thought, specifically abstract expressionism and existential philosophy. Throughout the 1960s, Halcomb became the face of authentic, noncommercial, white folk music — someone who channeled Appalachian tradition and an avant-garde energy into his art. He became a muse for Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, and other young middle- and upper-class Americans who looked South for their musical roots and artistic inspiration.8According to W.K. McNeil, Will Wallace Harney's 1873 article, "A Strange Land and a Peculiar People," is significant "not so much for the material he reports but in his characterization of Appalachia as a place in, but not of, America." William Goodell Frost's 1899 article for the Atlantic Monthly titled "Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains," reinforced the idea of Appalachian distinctiveness and homogeneity for a new generation. Frost believed Appalachia had finally awoken from a "Rip Van Winkle sleep" and needed the guidance of northern missionaries to bring progress to the region while sustaining unique cultural customs. Both articles are collected in W.K. McNeil, Appalachian Images in Folk and Popular Culture (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1995). For more on the construction of the image of the Appalachian folk during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries see Henry Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the America Consciousness, 1870–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978); David Whisnant, All That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983); Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990); Jane S. Becker, Selling Tradition: Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930-1940(University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

|

| New Lost City Ramblers, Out Standing In Their Field, Vol. II 1963-1973 |

Halcomb emerged as a solitary and creative genius, a characterization that echoed the modernist cultural context Cohen imbibed while living in New York among the Beats and abstract expressionist artists. Halcomb's art seemed to display for Cohen the same force, dynamism, and vitality of artists like Jackson Pollock or Robert Rauschenberg. The emotional intensity of Halcomb's music also resonated deeply with Cohen and his peers, creating a legendary reputation for Halcomb. His hard life in the Kentucky mountains heightened his authenticity as folk musician; the sorrow and anguish that hovered over every song seemed to emanate from actual experiences rather than abstract lyrics or mournful melodies. Roscoe Halcomb, the man and his music, soon came to symbolize for Cohen and his peers in the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s, the uncompromising polar opposite of popular culture circulating on the airwaves and in the magazines of urban and suburban America. If every aspect of 1950s American culture seemed a cheap imitation, then Halcomb and eastern Kentucky seemed like an authentic people and place apart.9For more on the "folk" and authenticity see Regina Bendix, In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997); Gene Bluestein, Poplore: Folk and Pop in American Culture(Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994); Filene, Romancing the Folk; Becker, Shared Traditions. They may have had access to modern conveniences such as radio, television, and record players, but, for many folk revivalists, their seeming isolation and poverty mitigated these corrupting influences and preserved vestiges of raw folk expression.10The myth of Appalachia as an isolated region in America has deep roots that reach back into the nineteenth century. Henry Shapiro and Allen Batteau among others have demonstrated how fiction writers beginning in the 1870s created the enduring myth of isolation and "otherness." As Shapiro notes, isolation was never just a "descriptive characteristic" but also a way to refer to "a state of mind, an undesirable provincialism resulting from a lack of contact between mountaineers and outsiders" (77). Other Appalachian historians have in recent years produced probing histories that undermine ideas of the region's social and economic isolation from the rest of America. Ronald L. Lewis has reviewed recent scholarship on Appalachian history and discovered "little empirical evidence for the proposition that Appalachian culture was the product of continuing frontier isolation." See Ronald L. Lewis, "Beyond Isolation and Homogeneity: Diversity and the History of Appalachia," in Dwight B. Billings, et al, eds., Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 21-43; Dwight B. Billings, Mary Beth Pudup, and Altina L. Waller, "Taking Exception with Exceptionalism: The Emergence and Transformation of Historical Studies of Appalachia," in Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Mary Beth Pudup, Dwight B. Billings, and Altina Waller (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 3. For the cultural and literary origins of the myth of isolation see, Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind; Whisnant, All That Is Native and Fine; Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia; McNeill, ed., Appalachian Images in Folk and Popular Culture.

Halcomb's admirers romanticized his apparent isolation not only from urban America and popular culture, but also from his own community in Perry County, Kentucky. "He was so much of the mountains and their culture," wrote Mike Michaels, a participant in the folk revival from Chicago who knew and visited Halcomb in the 1960s, "but the artist within him that had created such unique music ultimately set him apart from his family and neighbors." Another folk revivalist, Jon Pankake, highlighted similar contradictions within Halcomb's music itself which he described as "at once so archaic and so abstractly avant-garde . . ." "the exhultation [sic] of despair . . ." "the most moving, profound, and disturbing of any country singer in America." His image as a torchbearer of Appalachian tradition relied in part upon emphasizing his roots in the poor and, apparently, isolated hollows of eastern Kentucky while his image as creative genius and avant-gardist required his depiction as separate from the people and places that comprised the region. What made him unique necessarily made him isolated. Through photographs, films, and appearances at folk music festivals, Halcomb became the image of the solitary existential hero who expressed life's dilemmas in anguished, uncompromising music.

This essay examines the thought and documentary work of folk revivalist John Cohen. It explores motivations and preconceptions that brought him to eastern Kentucky, the relationships he had there with musicians such as Roscoe Halcomb, and the influential documentary images and recordings he produced. First, I examine Mountain Music of Kentucky (1960), the first record to feature Cohen's recordings, his photography, and Halcomb's image. Cohen's 1959 photographs evoke the elegant realism of Farm Security Administration photographers of the 1930s and 1940s, combined with the psychological depth of Robert Frank's photographs from the 1950s, and Helen Levitt's poetic and candid images of everyday life in Spanish Harlem during the 1940s.

|

| Map of sites that Cohen documented, 1959-1963. (Base Map Data: US Census Bureau). |

Next, I explore Cohen's first attempt at documentary film. Realizing that he could convey a wider experience of life in eastern Kentucky with film than through photography and sound recordings alone, Cohen returned to Kentucky in 1962 to make a documentary about Halcomb's Perry County milieu called The High Lonesome Sound: Kentucky Mountain Music (1963). Although Cohen had never used a motion picture camera and had little knowledge of the history of documentary film, The High Lonesome Sound expressed his response to the music and culture of Appalachian Kentucky and captured the tension between the realist and romantic motives intrinsic to documentary work during this time: "I wanted to make a visual statement encompassing both documentary and subjective ideas, to find a way to integrate feeling with seeing. I was often torn between a need to document (describe) [Cohen's parenthesis] what was in front of me and the desire to follow intuitive visual impulses. This set up an internal dialog, a debate between conceptual and creative thinking. I walked the line between these ideas all my life."11John Cohen, There Is No Eye: John Cohen Photographs (New York: Powerhouse Books, 2001): 15.

I conclude with a look at Halcomb's relative fame, and after the film, his continued struggle to survive amid the poverty of eastern Kentucky and his failing health. Halcomb never sought wide recognition. More than anything, he simply wanted to make a living for himself and his family. Work, not music, primarily defined him. Halcomb enjoyed the opportunities to perform and to make friends outside of Appalachia, but the legend that grew around him, during and after his life, obscured the hardships and pain that he endured.

Cohen's Musical and Artistic Awakening

In 1948, at the age of sixteen, John Cohen first heard Woody Guthrie's Dust Bowl Ballads at summer camp at a site called Turkey Point, north of New York City. The music entranced him. Guthrie's ballads and other albums of old songs and fiddle tunes sparked not only Cohen's fascination with old-time music, but also his rebellion against mainstream culture.12Cohen interview; Cohen, There Is No Eye, 22. At the same camp, Cohen also got an introduction to Kentucky mountain music and learned how to both build and begin to play a banjo. Woody Wachtell, a camp counselor, had been to Kentucky with Margot Mayo, founder of the American Square Dance Group, whose uncle, Rufus Crisp, was a banjo player from Allen, Kentucky. Crisp had recorded for the Library of Congress during the 1940s and '50s. Wachtell and Mayo made recordings of Crisp who, in turn, taught Wachtell about the banjo. Wachtell, as Cohen remembered, "conveyed such joy with his music . . . it was astounding to me . . . it had the feeling that it was something that I could do." Cohen also listened to music collected by John and Alan Lomax in the southern mountains while attending camp. A record called Mountain Frolic gave Cohen his first glimpse into the world of old-time music and string bands. When Cohen returned to his suburban high school in the fall, familiar with sounds from Appalachia, and interested in playing the guitar and banjo, he began to feel alienated from his peers. "I was the only person — the only person — playing a guitar in high school," he recalled, "and the only one singing these kinds of songs . . . which didn't make me special . . . it made me seem weird, you know, strange."13Cohen interview.

Cohen's sense of alienation persisted when he attended Williams College in 1950. Fraternities dominated the school's social scene and he met no one who shared his fascination with folk music. He found solace playing the banjo in his room and listening repeatedly to the Library of Congress recordings in the school's library. At night, he tuned his radio to WWVA and listened to country music broadcasted many miles to the south. The sounds seemed alien, but deepened his fascination for Appalachian music. "The songs spoke of Honky Tonk life and cheating wives and husbands on the one hand, and of the longing for home, farm and tradition, on the other." Enraptured, Cohen spent his first summer after college hitchhiking south to experience the music firsthand. When one of his rides stopped for gas somewhere in Virginia late at night, Cohen noticed the bugs swarming around the station's lights as a radio outside blared Flatt and Scruggs. He had heard Flatt and Scruggs before, but never so close to the source. They hit him hard.14Cohen interview; John Cohen, "A Visitor's Recollections," in Allen Tullos, ed., Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South (Southern Exposure, Vol. 5, Nos. 2-3, 1977): 115; Cohen, There Is No Eye, 24.

Fed up with the preppy culture of Williams, Cohen transferred to the art school at Yale in 1951 and fell in with a group of students and professors who played a profound role in shaping his career. Cohen found Tom Paley, a mathematics graduate student, who shared his passion for southern folk music. Cohen, Paley, and other enthusiasts started hosting and promoting "hootenannies" in 1952 and 1953. Early on, the "hoots" attracted only a few art and graduate students, but word spread and the next thing Cohen knew "two or three hundred students were showing up to sing with us on Friday nights."15Susan Montgomery, "The Folk Furor," Mademoiselle (December 1960): 100.

|

|

Playing hoots and meeting other musicians occurred alongside Cohen's formal education. He studied painting with Josef Albers and photography with the Swiss artist Herbert Matter who introduced him to another Swiss photographer "in retreat from the Swiss bourgeois life," Robert Frank.16Cohen interview; Cohen, There Is No Eye, 82. After graduating from Yale, Cohen moved to New York City and, for a short time, lived next door to Frank on the lower East Side at 32 3rd Ave. In 1957, before his book The Americans was published, Frank showed Cohen a stack of photographs he shot during his travels across the country. The floor was strewn with prints. Frank's photographs captivated Cohen and showed him another way of seeing his surroundings. While the FSA photographers revealed the roots of poverty and social patterns, Frank focused more on the interiority of American life — the "hollowness and corrosion" that lurked beneath the sheen of mainstream middle-class society. Cohen believed Frank's photographs evoked a visceral and subjective response that focused on emotion and feeling. "They hit me," Cohen recalled. "It was no longer FSA, it was no longer news, and it wasn't art either, you know, it wasn't [Edward] Weston."17Cohen interview; Cohen, There Is No Eye, 82-83. For the distinction between Frank and FSA photographer Walker Evans, see William Stott, "Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and the Landscape of Disassociation," Arts Canada 31 (December 1974) and Leslie Baier, "Visions of Fascination and Despair: The Relationship Between Walker Evans and Robert Frank," Art Journal Vol. 41, No. 1 (Spring 1981): 55-63; Tod Papageorge, Walker Evans and Robert Frank: An Essay on Influence (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1981); John Bromfield, "The Americans' and the Americans," Afterimage Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (Summer 1980): 8-15.

Cohen's friendship allowed him to work on the set of Frank's 1959 experimental film about Beat culture, Pull My Daisy, which was based on a script by Jack Kerouac. Cohen served as the set photographer, taking stills of the filming. The cast Frank assembled comprised a 'who's who' list of New York's Beat scene during the 1950s: Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Larry Rivers, David Amram, and Peter Orlovsky. Though Cohen recalled that Frank had an idea of structure, ultimately, "improvisation seemed to dominate the production." Cohen marveled at the way Frank carefully composed images in the camera rather than dominate the production. "Frank's images," Cohen recalled, "caught the feel of loft living and the crazy openness of the Beat poets. In this setting the kitchen sink, the refrigerator, and even the cockroaches took on grimy meaning."18Cohen interview; Cohen, There Is No Eye, 106.

|

| Still from Robert Frank's Pull My Daisy (1959). |

Frank's composed images and evocation of the "feel" and material attributes of Beat life influenced Cohen's understanding of documentary as a means to portray both an objective reality and subjective feeling and emotional response. This tension between the need to document and describe and the desire to follow what Cohen called "intuitive visual impulses" defined his documentary vision. Ultimately, Cohen rejected any pretension to cool detachment but, rather, embraced Frank's example of documentary as art, a mode of expression in which subjectivity and interiority guided composition. Observing Frank's filming on the set of Pull My Daisy in 1959 would provide Cohen with a model when he began his own documentary filmmaking in Kentucky.

During the late 1950s, Cohen also worked in New York as a photojournalist. As he remembers, the life of a freelance photographer during this period was frustrating and uncertain. He and other photographers responded by creating an informal organization of independent photographers that held meetings at Cohen's loft. Members included Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, among others. Cohen's assignments were mostly dull and unsatisfying, although he did get an eight-page spread in Esquire for a photo essay on motorcyclists at a rally. Life also paid him for his photographs of the Beats taken on the set of Pull My Daisy. Cohen used the money he had made from Life to finance his first trip to Kentucky during the late spring and summer of 1959. Cohen hoped his trip would help establish an independent means of making a living, one that fulfilled creative desires rather than stifling them, as he described, "I had to make my own means of working independently."19Cohen, There Is No Eye, 82 and 118; Cohen interview; Blake Eskin, "His Worst Critic Proved Wrong," New York Times, November 18, 2001: 38.

John Cohen in the Folk Revival

|

| George Pickow, New Lost City Ramblers, circa 1960. |

Cohen's idea for a Kentucky trip also came from his involvement with an old-time music group he formed in 1958 in New York City with Tom Paley, his friend from Yale, and Mike Seeger, Pete Seeger's younger half-brother. The three called themselves the New Lost City Ramblers. Cohen's simultaneous participation in the burgeoning folk-revival scene and the Beat and abstract expressionist worlds made him a unique figure in the late 1950s underground. He bridged both worlds in a way almost no one else did. Like Beat poetry and abstract expressionism, folk music for Cohen represented an antidote to mainstream culture. Cohen wanted the group to transcend entertainment and give their audience a deeper appreciation for the roots, people, and culture of the music they played.20Jon Pankake, "The New Lost City Ramblers: The Early Years, 1958-1962," liner notes to The Early Years, 1958-1962, perf. The New Lost City Ramblers (Smithsonian Folkways CD SFW 40036, 1991).

The three musicians also bonded over a mutual obsession with Harry Smith's seminal Anthology of American Folk Music, which came out on Folkways Records in 1952. The collection's powerful combination of creative packaging, Smith's humorous annotations, and the haunting sounds of a distant folk geography seduced all three. Southern music provided a vicarious connection to a rural idyll very different from Long Island or Greenwich Village. When Cohen and his friends listened to the Anthology's songs they heard the "voices of people from the rural tradition" facing their own anxieties and singing about them in their own style. The revivalists projected thoughts, emotions, and concerns onto the psyches of rural folk singers who, they believed, shared their internal anxieties. They used the language of existentialist philosophy prevalent in the literature and art of the 1950s' American underground and intelligentsia to construct their image of the folk performers on the Anthology, such as the Carter Family or Dock Boggs, who, they believed, shared their sense of alienation from modern America. Roscoe Halcomb in particular became the embodiment of this existential hero.21Gura, "Southern Roots and Branches," 62-63; Goldsmith, Making People's Music, 259. For more on popular and critical reception of Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music during its release in 1952 and its reissue in 1997, see, Katherine Skinner, "'Must Be Born Again': Resurrecting the Anthology of American Folk Music," Popular Music, Vol. 25, No.1 (2006): 57-75.

|

| Peter Feldman, John Cohen |

When Cohen and the Ramblers reproduced the sounds and emotions of the old songs in their performances, they hoped to convey the same power and authenticity they discovered when listening to old 78s and LPs. "There are certain qualities which we demand from the music," Cohen wrote in Sing Out! magazine in 1961; "a sense of immediacy, of personal involvement, a sense of tradition as well as appreciation for that which carries things to a point where they can go no further — a feeling of 'way out,' a rejection of compromise for commercial or artistic reasons, an obsession with the song material . . ."22John Cohen, "The Revival," part of a symposium titled "Folk Music Today," Sing Out!, vol. 11, no. 1 (Feb – March 1961): 23. Cohen's desire for immediacy, experience, and transcendence — a "feeling of 'way out'"— guided not only his relationship to traditional or old-time music but also shaped his documentary work and the nature of his eventual portrayal of Roscoe Halcomb. Cohen drew from the same aesthetic and emotional well when playing old-time music or making photographs and films about musicians and their cultures.

Two years earlier in the pages of Sing Out! Cohen responded to charges leveled by Alan Lomax, the most important folk music collector of the era, who had accused "citybillies" and "folkniks" of not understanding the real emotion of rural singers in their efforts to play authentic folk music. Cohen countered that Lomax assumed an elitist position that characterized him as a "holy ghost" sent from on high to reveal the gospel of true folk music. Cohen portrayed Lomax as out-of-date and unaware of the new ideas that characterized the folk revival in the United States. While Lomax had been out of the country collecting folk music across Europe (and avoiding the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings), he missed folk music's shift in emphasis from what Cohen characterized as "social reform or world-wide reform" to a movement "focused more on a search for real and human values."23John Cohen, "In Defense of City Folksingers," Sing Out! vol. 9, no. 1 (Summer 1959): 32-33.

Just as there was a shift in documentary photography during the mid-twentieth century from producing photographs that exposed injustice and championed social reform to a perspective more explicitly focused on subjective experience, Cohen's acknowledgement of the folk revival's existential search signaled a similar transformation that he believed Lomax did not appreciate. The Old Left and Popular Front politics that Lomax adopted while growing up during the New Deal and beginning his important work as a collector and concert organizer during the 1930s had lost their relevance. Cohen looked back to the New Deal era for aesthetic, not political, inspiration. The New Deal and Depression, he believed, were a time when people did search for values, when people did have a cause to fight for, something which defined their place in society. In his own search for values, Cohen used the past to give meaning to an uncertain and seemingly nihilistic present. His quest also pushed him to do more than learn and practice the music of old-time musicians. He felt he needed to go where they lived, to photograph and film their lives, and to experience and embrace their culture.24For more on the different contexts, politics and aesthetics of twentieth century folk music revivals in America, see Robert Cantwell, "When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival," in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, Neil Rosenberg, ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); Ron Eyerman and Scott Baretta, "From the 30s to the 60s: The Folk Music Revival in the United States," Theory and Society Vol. 25, No. 4 (August 1996): 521-522. For more on twentieth century folk revivals in the United States see Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997); Ronald D. Cohen, Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and America Society, 1940-1970 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002); Ron Eyerman and Andrew Jamison, Music and Social Movements: Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Philip F. Gura, "Southern Roots and Branches: Forty Years of the New Lost City Ramblers," Southern Cultures vol. 6, no. 4 (Winter 2000); Ray Lankford, Folk Music U.S.A.: The Changing Voice of Protest (Schirmer Books, 2005); Robbie Lieberman, My Song Is My Weapon: People's Songs, American Communism, and the Politics of Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005); Neil Rosenberg, ed. Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); Dick Weissman, Which Side Are You On?: The Inside History of the Folk Revival in America (Continuum, 2005).

Recalling the New Left's rejection of top-down leadership and authority during the 1960s, Cohen argued that he and his peers in the folk revival were not "looking for someone to lead us" because they were "looking within themselves." There was no particular "truth," no law or formula that defined folk expression. "The emotional content/ of folk songs is a different thing to different people," Cohen argued, "and it is hard to say that there is a single, correct way to emotional content/." Echoing an old refrain in the romantic tradition, truth, according to Cohen, was "available to anyone who will seek it — and there will be eventually be as many ideas of truth as there are people pursuing it . . . There is no truth except that which we make for ourselves."25Cohen, "In Defense of City Folksingers," 32-33. On romanticism's rejection of universal truths and absolutes see Isaiah Berlin, The Roots of Romanticism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999): 138, 140, 146-147. "What Romanticism did," according to Berlin, "was to undermine the notion that in matters of value, politics, morals, aesthetics there are such things as objective criteria which operate between human beings. . . . The notion that there are many values, and that they are incompatible; the whole notion of plurality, of inexhaustibility, of the imperfection of all human answers and arrangements; the notion that no single answer which claims to be perfect and true, whether in art or in life, can in principle be perfect or true – all this we owe to the romantics" (140,146). Depression songs and eastern Kentucky, where an actual economic depression was ongoing, provided Cohen and others with a vital experience that counteracted the aesthetic and emotional landscape of 1950s suburbia. Writing in the liner notes to the Ramblers' Songs of the Depression, Cohen argued, "there is an element in young people today which feels a yearning for the thirties as a desire to have a clear and humane cause to fight for." Early Ramblers concerts even advertised themselves with the Blue Eagle of the NRA and the slogan, "I am lost. Take me back to 1932."26Jens Lund and R. Serge Denisoff, "The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions," Journal of American Folklore, vol. 84, no. 334 (Oct. – Dec., 1971): 400. Robert Cantwell, a historian of the folk revival, has placed its participants in historical context, showing how their yearnings and cultural expressions sprang from the particular "psychosocial and economic setting of postwar America." Folk revivalists, those born towards the end of the depression to around the late 1940s (Cohen is on the older end of this time frame), "grew up in a reality perplexingly divided by the intermingling of an emerging mass society and a decaying industrial culture." New technologies, new familial structures, new networks of communication, new neighborhoods, and new forms of entertainment erased the world in which their parents had grown up where, for many, a sense of community and belonging revolved around ethnic identity, work, or small town and rural life. The 1930s and the Depression seemed like another country, a more authentic place, a place where the struggle for survival sharpened experience. The behemoths of bureaucratization, conformity, and consumerism threatened to crush the search for an unmediated life. Robert Cantwell, "When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival," 45-47; see also Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996): 328-337.

|  |

| NRA (National Recovery Administration) Blue Eagle Poster. This New Deal program from the 1930s was popular with workers. | Fan card from the New Lost City Ramblers 1960 concert tour featuring their own NRA eagle. Courtesy of John Cohen. |

It was also during the 1930s that John Lomax and others recorded some of the haunting songs Cohen listened to while in college. The Great Depression was an incubator of authentic music according to folk music fans. The urge to depart the 1950s for the 1930s sprung from the revivalists' appreciation of the artistic and aesthetic images of the decade, as transmitted through FSA photographs, field recordings, and Harry Smith's Anthology, instead of nostalgia for the Old Left or New Deal liberalism. Cohen imbued the leftist idea of a political cause with both aesthetic and psychological concerns.

Writing for Mademoiselle magazine in 1960, Susan Montgomery wondered what lurked at heart of the folk revival: "Why American college students should want to express the ideas and emotions of the downtrodden and the heartbroken, of garage mechanics and mill workers and miners and backwards farmers. . . ." She noted that young middle-class folk revivalists were "desperately hungry for a small, safe taste of an unslick underground world." Folk music for them represented a "slight loosening of the inhibitions, a tentative step in the direction of the open road, the knapsack, the hostel." In a "brutal and threatening" world clouded by prospects of nuclear war and a culture littered with consumerism and slick popular music, folk music provided an experience that broke through the deadening influences of middle-class upbringings. Some of the most intense revivalists, those most committed to embracing and understanding the roots, styles, and aesthetics of American folk music, maintained a level of interest and commitment that extended beyond participating in group folk sings, festivals, or hootenannies. These young adults diligently learned their instruments and the significance of the songs they sang, becoming, as John Cohen acknowledged, the "best city folk musicians." These same people, Montgomery observed, often wished "they'd come from the Kentucky mountains or (depending on the music they play) that they had been born Negroes. . . . The sounds and emotions these students sing so furiously are eventually incorporated into their consciences. They are, in a sense, bedeviled people who, even though they are fine musicians, should be counted among the casualties of contemporary American life." The folk revival, according to Montgomery, functioned as a religious movement led by idealists and romantics like John Cohen — "seekers, value hunters and extremists who are willing to go all the way for something they believe in . . ."27Montgomery, "Folk Furor," 99 and 118. For more on this generation's search for authenticity and an experience to break through the confines of contemporary middle class culture see Doug Rossinow's study of the New Left and the Civil Rights Movement, The Politics of Authenticity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

In 1959, Cohen recalled being "disgusted with the city, grey dirt and second-hand folk music, curious about Kentucky mountains, Elizabethan-like ballads, dulcimers, fierce banjo-playing, hillbilly music, bloody Harlan, mining songs, depressions and striking miners." He said one purpose of his Kentucky trip was to establish respectful relationships between city and country musicians. "If the city wants and needs folk music in its soul," he wrote about his trip in 1960, "then its exchange with country musicians must be a two-way affair. If we feel a desire towards their outlook on music, we must be willing to understand their way of life and to respect them as people who have something to offer in their way."28John Cohen, "Field-Trip – Kentucky," Sing Out!, vol. 10, no. 2 (Summer 1960): 13.

Cohen was certainly not the only person to mythologize the Kentucky mountains as a bastion of authentic folk music, and he was not the only person making field recordings in the area in 1959. Despite jokes that young folk song collectors were overrunning the Appalachians with recording studios dragging behind them, there were actually only a few folk song collectors working during this time. Cohen, his bandmate Mike Seeger, and Ralph Rinzler, a former Swarthmore student and friend of the Seeger family came to the southern mountains. The only other visible collector in Kentucky that year was Cohen's nominal nemesis, Alan Lomax, who visited the southeastern part of the state in early September, well after Cohen had returned to New York City.29Cohen, "A Visitor's Recollections," 116. Cohen recalled speaking to Lomax in February during the "Folk Song '59" festival that Lomax organized at Carnegie Hall. Cohen mentioned to Lomax his intention to travel to Kentucky to record and photograph musicians. Lomax sensed a competitor and tried to dissuade the naïve Cohen with the cautionary tales of a seasoned folk song collector who had recorded musicians in the Kentucky mountains during the 1930s and early 1940s. "Oh, well you're going to places where they don't have electricity," he warned, telling of carrying heavy batteries up steep hills.30Cohen interview.

But Lomax was also hardly the first song collector in Kentucky. Long before he and Cohen arrived in 1959, folklorists and amateur collectors traveled there in the early twentieth century. Most notable was the Englishman Cecil Sharp, who had hoped to find the Elizabethan ballads preserved by years of isolation from modern industrial society.31See for example, Josephine McGill, Folk Songs of the Kentucky Mountains: Twenty Traditional Ballads and Other English Folk-Songs (New York: Boosey & Co., 1917); Loraine Wyman and Howard Brockway, Twenty Kentucky Mountain Songs (Boston: Oliver Ditson, Co., 1920); Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles, English Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians (London: Oxford University Press, 1932. For a historical overview of these early collectors see Whisnant, All That Is Native and Fine and Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and the Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978). The romanticism expressed by these early collectors differed from Cohen's. The ballad collectors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries kept ears attuned for Child ballads, supposed vestiges of old English lineage. Cohen went to Kentucky in part because of its mining culture, which he believed produced the closest thing he would ever get to a setting reminiscent of the 1930s. In 1959, "while the rest of America was busy and prosperous," Cohen wrote, "Kentucky was experiencing a depression caused by troubles in the coal mines." He hoped to find songs sung by miners that would tap into the pathos of a recent past when rural Americans struggled nobly in the face of deprivation and hardship and produced emotionally resonant music. Unlike earlier collectors, Cohen also saw fieldwork as a personal quest for meaning, not a folkloric, literary, or academic safari. "The opportunity to visit traditional artists in their homes was seen as a privilege," Cohen recalled, "an activity of reaching out, a dynamic process that might bring meaning and music to one's own life."32Cohen, There Is No Eye, 120; Cohen, ed., "Wasn't That a Time!", 26; Cohen, "Field Trip — Kentucky," 13.

During the late 1950s, the young folk singer Jean Ritchie from Viper in Perry County contributed to Cohen's and the folk revival's romantic imaginings of the mountains. Ritchie left Kentucky in the early 1950s to live in New York City and get involved with the burgeoning folk scene. Young revivalists like Cohen loved her early recordings for Folkways, which colored their perceptions of the mythical mountains. In February 1959, Robert Shelton, who covered the American folk music scene for the New York Times, declared Ritchie "one of the finest authentic traditional folk singers we have in the United States today. She is the heir of a tradition that goes back to the pioneers who settled the Kentucky Cumberlands. Her forebears lived in isolated areas where customs were tenacious and songs were passed on from one generation to the next." In 1955, Oxford University Press published Ritchie's memoirs and family history in Singing Family of the Cumberlands. In 1959, the Riverside label released an LP by the same title on which Ritchie used excerpts from the book to tell stories about growing up in Kentucky. "Her tales are unaffected, often poetic recollections of a community that was slow moving but often quickened by the vitality of human contact," Shelton wrote. "Here was the sort of family living, except for its material poverty, that the sloganeers of 'togetherness' and The Saturday Evening Post cover artists might dream about."33Robert Shelton, "From Old Kentucky," New York Times, February 1, 1959: X17.

|  |

| George Pickow, Jean Ritchie and Oscar Brand at WNYC in New York City, 1947. | George Pickow, Jean Ritchie and Roscoe Halcomb, early 1960s. |

Cohen's first encounter with Ritchie's songs came over the radio waves on a program hosted by Oscar Brand in the early 1950s. Cohen's father had purchased a wire recorder for him, and he would make recordings of Brand's show and send them to his brother who attended college at University of California, Berkeley. Ritchie provided Cohen with images of Kentucky that differed from those presented by Merle Travis, a popular country singer and songwriter also from Kentucky who sang about the exploitation of miners. Later, Cohen got to know Jean Ritchie when the New Lost City Ramblers shared bills at clubs in the Village, at Izzy Young's folklore center, Carnegie Hall, and other venues. Ritchie was a distant cousin of Roscoe Halcomb who lived just below Viper in Daisy. She remembered Halcomb as one of the "'good old boys'" whom she occasionally saw "making music at square dances and set-runnings around the community." Ritchie drew upon family and community connections to provide Cohen with a list of names and contacts in Perry County.34Cohen interview; Jean Ritchie, e-mail correspondence with the author, October 19, 2006. For an overview of Kentucky's folk and country music history see Charles K. Wolfe, Kentucky Country: Folk and Country Music of Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1982).

John Cohen in Kentucky, 1959

|

In addition to the connections provided by Ritchie, Cohen contacted the United Mine Workers and the Library of Congress before heading to Kentucky by bus. He had heard about John L. Lewis of the UMW, and of the strikes and battles in "bloody" Harlan, and he figured if he was searching, in part, for mining songs it might be a good idea to check in with the union. UMW officials in Washington gave him the name of the regional director in Pikeville, the first place Cohen stopped when he got to Kentucky. The town bore no resemblance to what he had imagined. It had the feel of an "urban cluster" — something Cohen thought he had left behind. "This isn't going to work," he told himself.

During the late 1950s, Pikeville had a population of about six thousand people and, according to anthropologist Allen Batteau who studied the region during the 1960s, was a "commercial outpost in the midst of a mountain wilderness. After a hundred miles of travel through baffling curves and folded hills, through villages like Dwale and Ivel and Betsy Lane, in Pikeville one could find the latest styles and fashions of the American economy." Pikeville's signs of middle-class consumerism and commercialism did not fit with Cohen's image of Kentucky as a land ripe with "Elizabethan-like ballads . . . fierce banjo-playing . . . mining songs . . . and depressions . . ." He left for another commercial center, Hazard, about thirty miles away, partly because it was close to the Ritchie family's village of Viper where he had contacts. Cohen passed the first days of his trip establishing supportive connections.35Cohen interview; Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990), 175-176. Batteau says a "trip to Pikeville, Kentucky, in 1959 was an expedition into the heart of darkest Appalachia." Leaving from Huntington, West Virginia, a traveler passed "ramshackle cabins, swinging footbridges extending to similar cabins on the other side, abandoned carcasses of Fords and Chevrolets, piles of garbage on the riverbank, and black-faced coal-diggers crawling out of dog-hole mines. . . ." (176) His source for this description is unclear.

In 1959 Cohen did not have a reference source like Harry Caudill's Night Comes to the Cumberlands, which came out in 1963. Instead, he relied on W.J. Cash's 1941 The Mind of the South, a book that was hardly relevant to life in Appalachia. Cash's reading of southern history had taught how plantation owners tried to establish a Herrenvolk democracy that reinforced racial divisions and mitigated class conflict between white planters and yeoman farmers. Cohen looked out at the economically depressed mountains searching for things that reinforced and added to his analysis. He recalled driving with old-time musician Willie Chapman over to Hyden in neighboring Leslie County. On the way they passed a burning coal truck by the side of the road, a possible casualty of an effort to organize workers who ran the ramps and tipples where truck miners brought their coal. When they passed by later that day and the truck was still on fire, Chapman suggested to Cohen that nobody wanted to intervene because they would probably get shot. "So then you realize," Cohen recollected, “that it was much more than meets the eye, or anything you looked at had a lot about it . . . ." Photographing provided Cohen with a way to make sense of what he saw, to give structure and meaning to a place that was confounding his preconceptions.36Cohen interview; Henry C. Mayer, "Coal Mining," in John E. Kleber, ed. The Kentucky Encyclopedia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 210.

|

| Downtown Hazard, Kentucky, late 1950s from www.hazardkentucky.com. |

Before he started photographing, Cohen spent a few days walking the streets of Hazard, observing and thinking about how he wanted to represent the region. He considered the "depressions" that drew him to Appalachia, "mining people vs. farming people, religious music vs. dance music." He knew he wanted to avoid the "obvious," what he had seen in photographs and what he knew people like the editors at Life expected to see: hillbillies amid squalor. He avoided stereotypical pictures, but chided himself later, knowing that by rejecting these "good" images, he also "kicked out the possibility of sale" for his photographs. Nevertheless, as Cohen wrote his friend Ross Grosman in a letter from Kentucky in 1959, "this leaves me with a strange sense of freedom in relation to what I finally do produce — for it can come from a more personal or profound part of myself." For Cohen, documentary expression and the "seeking out of ideas, feelings, situations etc. to photograph" depended on a "very subjective sequence of following whims and hunches — which are not logical immediately." If they seemed logical, Cohen purposefully avoided them. The friction between the "logical" and "literary," or the reality Cohen witnessed versus the one he imagined, provided the creative tension he felt was necessary to produce beautiful photographs.37John Cohen to Ross Grosman, June 1959. Letter in John Cohen's possession, photocopy made by author, January 2008.

|  |

| John Cohen, Two men on porch, Premium, KY, 1959. | John Cohen, Two women, Premium, KY, 1959. |

Cohen was keenly aware of the potential for trouble with local authorities and residents as he roamed with a camera and a recording machine. He sensed friendliness at times from the locals but wondered about how much of it was façade. "On one hand," he said, "when you get to a new place everything is exciting but at the same time everything is potentially dangerous." Cohen visited the sheriff's office in Hazard and told them, "If you see this weird guy walking around with a camera, it's me! If they pull me in, you know, it's me." He compared himself to Alan Lomax who traveled the country making recordings of strangers. While Lomax could use his association with the Library of Congress to lend credibility, Cohen had only a loose connection with the Ritchies and the UMW. "I expected and encountered an unmistakable sense of mistrust from many quarters."38Cohen interview; Cohen to Ross Grosman; Cohen, "Field Trip — Kentucky," 13; Cohen, liner notes to Mountain Music of Kentucky (Smithsonian Folkways CD 40077, 1996), 24.

Clip, "Banjo" Bill Cornett, "Buck Creek Girls," Disc One, Mountain Music of Kentucky CD, Smithsonian Folkways CD 40077.

He remembered reading an article in Life magazine about how federal revenuers disguised as folk song collectors scoured the Appalachians after Prohibition hoping to dupe unsuspecting bootleggers and moonshiners. One of the first musicians he recorded, Bill Cornett, told him that folk song collectors were suspect. Cornett possessed a unique banjo style replete with odd phrasings and tunings. He had established himself as a local hero by singing "The Old-Age Pension Blues" on the floor of the Kentucky legislature. Once, while playing at the National Folk Festival, Cornett was told to keep an eye out for suspicious folklorists who would steal his music and copyright it in their own names. When Cohen arrived at Cornett's house for the first time he brought along two familiar UMW officials. Cornett sang "vigorously" on his porch for Cohen who described him as a "terrific performer, his rich musical ideas pouring out from the first moment he started playing for us." Yet, Cohen "felt his apprehension" about playing for a suspicious "outsider." Cornett said he was wary of collectors and, consequently, declared ownership of each song after he finished singing. "He was a confident person," Cohen recalled, "yet seemed gruff and abrupt about the music he knew so well. He had little doubt about its importance and that he was preserving and passing on something precious and vital."39John Cohen, "The Lost Recordings of Banjo Bill Cornett," liner notes to The Lost Recordings of Banjo Bill Cornett (2005), Field Recorders' Collective, http://www.fieldrecorder.com/docs/notes/cornett_cohen.htm; Cohen, liner notes, Mountain Music of Kentucky, 26.

Cohen tried to understand where musicians' apprehensions came from and why they existed. Something larger than folk music, rooted in the long history of exploitation of the region, fueled the doubts and fears. "Suspicion starts with a feeling of being different from the mainstream culture," Cohen later asserted, "and comes down to a power struggle over who controls the means of representation." But what first attracted Cohen to Kentucky was its seeming difference. Instead of exploiting stereotypes, Cohen used this sense of difference to heighten his aesthetic experience of the musicians, their music, and their region. Kentucky mountain people, he wrote, "have been made to feel as if their own way is inadequate in the face of the sophisticated luxuries which bombard them from the national advertisements — and they know the stereotype which the national press has given of them, as ignorant, primitive and barefoot, and they resent it."40Cohen, "Field Trip — Kentucky," 13.

Cohen's awareness mixed with his own preconceptions to produce an image of eastern Kentucky that was humane, yet still mythic. Towards the end of his 1959 trip, he wrote again to his friend Ross Grosman about the impressions and ideas that shaped this documentary vision, revealing the tension between his desire to depict reality and a tendency toward romanticism. "It has been a hard time here in Kentucky and I just don't know how much I have accomplished." He particularly wondered about how the ideas and impressions "communicated on film." On the one hand, he felt a "certain spirit of this region is akin to Shakespeare's England, with motivations coming from a sense of gallantry + duty primarily. People here are rugged individuals." On the other, he witnessed a less idealized reality: "But still, there is something which isn't yet clear — which I can't get with. Although there is real + warm love within families — there is something extremely opposite that — which manifests itself in feuds, shootings, cuttings, etc."41John Cohen to Ross Grosman, second letter, June 1959. Letter in John Cohen's posession, copy provided for author. Domestic violence and murder occurred everywhere, but in Appalachia such acts became stereotypical "feuds" or signs of a deviant and primitive culture in the minds of the many Americans who knew little about the region. Cohen never associated eastern Kentucky with deviance or attributed violence to social pathologies. Instead, the cognitive dissonance caused by seeing 'Merry England'-in-Kentucky alongside explicit talk of familial violence only deepened the region's allure and mystery for Cohen, just as Roscoe Halcomb's apparent combination of the traditional and the avant-garde heightened the power and artistry of his music.

|

| John Cohen, Odabe Halcomb, with banjo, and Mary Jane Halcomb, Daisy, KY, 1959. |

These regional contradictions played out in person one day when Cohen drove with two brothers, both banjo players (aged sixty-eight and seventy-one), some seventy miles "out over wild mountain country," he wrote at the time, "to a section of these mountains . . . which is generally feared by people in Hazard – (who also have a fearful enough reputation themselves.)." Their destination was the home of an old fiddler whom Cohen wanted to photograph and record. "The music we made (I taped) was just exactly the greatest type which I've only heard before in the Library of Congress." And, yet, while he was among the fiddler's children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, he also overheard talk "about local murders, brothers killing brothers, wives killed by husbands, violent automobile accidents, snipings at coal operators, dirty dealing in coal contracting, moonshining, illegal hunting, etc." He also sensed the home held an "arsenal of guns" — and "all the while we were making all that nice old music."

|  |

| John Cohen, Boy with tin can banjo, Perry County, KY, 1959. | John Cohen, Boy with tin can banjo, Perry County, KY, 1959. |

The dissonance produced by the pleasant "old-time music" and the talk of murder, by the scene of a mother nursing her baby daughter and the whispers of fratricide, intoxicated and bewildered Cohen. Here he was in what looked like a particularly remote locale in Appalachia, recording seemingly ancient fiddle music while a television flickered in the corner of the house. "This was no log cabin," Cohen assured his northern friend. But when Cohen wanted to capture these visual impressions of Appalachia, his request to make photographs, unlike his request to record music, "was vehemently denied." Someone there had "something particular to fear" and the passionate refusal to allow photography filled Cohen with fear. Nothing else happened that day, he wrote, "but this is the atmosphere in which things operate once you leave your warm bed." The air of violence and suspicion wafted among more seemingly quaint and traditional scenes and sounds. The mixture created a place that seemed like no other in America, and that was susceptible to romanticizing.42Cohen to Grosman, second letter; Cohen interview.

Portraying Roscoe Holcomb

Cohen's documentation of the life and music of Roscoe Halcomb provides a compelling example of his fascination for Appalachia's seemingly conflicted culture. Here he found a place and people he saw as unique and mysterious because of the coexistence of traditional rural values alongside modern poverty produced by the mining industry. Cohen's work demonstrates how sound recording, photography, and film could present a dignified, respectful, and admiring portrait of a poor, middle-aged man from Appalachia in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Yet, because of the humanity and artistry of his work, Cohen also created a romantic narrative that portrayed the poverty Halcomb faced not as a product of an exploitative economy but as an aesthetic quality authenticating his music and validating its emotional force. Through Cohen's lens and microphone, poverty becomes not a burden but a precondition for beauty, a signifier of pure, powerful folk expression, of authenticity. Halcomb consented to documentation and exposure not because he wanted recognition for his music but because he believed Cohen truly appreciated it and that the younger musician might help him get a job.

|

| Still of Roscoe Holcomb playing guitar on his front porch from The High Lonesome Sound. |

When Cohen met Halcomb for the first time in June of 1959, he saw "a little, wiry person, stooped from hard physical work, coughing from asthma, black lung, and too much smoking." He was also quiet, gentle, unassuming and melancholic. After hearing him play "Across the Rocky Mountain," Cohen said Halcomb "seemed gigantic and full of inner strength." Cohen acknowledged his "Appalachian posture," his "hard life," and his "broken health," but these features, along with his conflicted relationship with old and new ways in the mountains "all gave an edge to his music." Something "heroic and transcendent" emanated from his voice. His singing "had a power that went straight to the listener's core." Cohen recalled, "His spiritual concern was beautiful and always present, revealed with a sharp, cutting expression of pain." The poverty Halcomb faced each day shaped the man and his music, but he never dwelled on it. Cohen, however, emphasized the poverty in Halcomb's life, not as a personal burden that took a toll on his physical and mental well-being, though Cohen certainly recognized this, but as an abstract force that gave the older musician's music its power, its "edge."43Cohen, liner notes to Mountain Music of Kentucky CD, 29; John Cohen, liner notes to Roscoe Holcomb: The High Lonesome Sound (Smithsonian Folkways CD 40079, 1998), 2.

|

| John Cohen, Men praying at Old Regular Baptist Church, Jeff, KY, 1959. |

In 1959, poverty was only one of Halcomb's many worries. Cohen sensed tension in his home. "His old ways were in conflict with the rest of the household. He was tolerated, but there was little feeling for his music, which was met with indifference or scorn." Earlier in his life he played with a small country band, but in 1959 if Halcomb played music, he played it alone, or occasionally with the older members of his family such as Mary Jane Halcomb and his adopted nephew Odabe Halcomb or with his old friend, Lee-boy Sexton. The children in his home (his wife Ethel's from a previous marriage to a miner who died in an accident) preferred to listen to rock n' roll music on the radio rather than the old ballads and blues Halcomb played on guitar or banjo. "It's not music," he said of rock n' roll in 1962, "it don't suit me . . . well the young generation can't hardly tell the difference no how cause they never heared nothing else much but that — but since this old music started back they're beginning to learn different."44Cohen, liner notes to Roscoe Holcomb: The High Lonesome Sound CD, 3-4 and 10; "Interview with Roscoe by John Cohen," taped in 1962 in Daisy, Kentucky. Transcript appears with the Folkways LP, Roscoe Holcomb: The High Lonesome Sound (Folkways Records, Album No. FA 2368, 1965).

The tensions and conflicts that defined Halcomb also had roots in social and economic changes affecting eastern Kentucky during the mid-twentieth century. "Roscoe was right in the center of conflicting Appalachian values," Cohen observed. Born in 1912, the agrarian world of Halcomb's youth gave way to one dominated by the mining and timber industries. "I was raised up when there were very few coal mines," Halcomb told Cohen, and "we made our living mostly in farming." He was also raised in the Old Regular Baptist church singing slow, somber, lined-out hymns. But as the Pentecostal-Holiness sect spread throughout the Appalachian region in the early twentieth century, he turned away from the Baptists who believed musical instruments were sinful and, instead, started playing guitar and banjo at a local Holiness church. Nevertheless, Halcomb still sang the Old Regular Baptist hymns at concert performances and alone at home "rekindling feelings, reliving lost pleasures, and immersing self and sentiments in days gone by," Cohen noted.45Cohen, liner notes to Roscoe Holcomb: The High Lonesome Sound CD, 3, 4, 6; "Interview with Roscoe Holcomb," 1.

Clip from Old Regular Baptist Church, "When We Shall Meet," Disc One, Mountain Music of Kentucky CD, Smithsonian Folkways CD 40077.

When Cohen first met Halcomb, he admitted he "had no idea what he was about." "I only knew that he usually worked at construction jobs and that the way he sang his songs had a great effect on me. Now, after almost forty years, I have come to realize I was hearing a man confronting the dilemma of his own existence." Cohen's trip to Kentucky also allowed him to confront his own existential struggles. Going to Appalachia resembled a pilgrimage, a search for meaning, values, and traditions missing from his own life in New York City. The region's apparent isolation and poverty, Cohen believed, nurtured music that combined tradition with powerful expressions of sorrow. It also sustained what he saw as folk customs that seemed like true expressions of a rural and traditional way of life he never knew in New York. In the summer, tomatoes and corn came fresh from the garden, in the fall at the first frost, Cohen noticed, "across the porches of East Kentucky, beautiful, bright-patterned, handmade patchwork quilts would appear, hanging out to be aired after summer in musty storage chests." He characterized what he saw as more than quaint tradition. The scene equaled "a visual experience" at the "Museum of Modern Art . . . the country version of contemporary aesthetics." Like Halcomb's music, eastern Kentucky's material culture seemed to blend the traditional and avant-garde. Cohen said in the late 1990s that these rural traditions and cultural expressions "never felt like 'folk art' or 'Americana,'" but at the time they signified to him a regional vitality and authenticity, attracting the "value hunter" Susan Montgomery identified in her 1960 article. "That part of Kentucky may be out of phase with the rest of the country," Cohen wrote in 1960, "but it can work well for itself right there. Those people have ways of doing things and attitudes which we in the city feel missing in ourselves — which is probably one of the big reasons we get so much from their songs."46Cohen, liner notes to Roscoe Holcomb: The High Lonesome Sound CD, 1; Cohen, "Field Trip — Kentucky," 13, 16.

Mountain Music of Kentucky

|

| Still from The Beverly Hillbillies. |

When Folkways released Mountain Music of Kentucky in 1960 (with an accompanying booklet of Cohen's notes and photographs), new stereotypes of the "hillbilly" were spreading through American culture. In the late 1950s and 1960s, an unprecedented migration of poor Appalachian people from the mountains to the mid-Atlantic and Midwest coincided with a federal War on Poverty that used the region as a symbol of America's failings. Fears of a hillbilly invasion combined with the discovery of Appalachia as an aberrant "pocket of poverty" to produce a mix of anxiety and wonder towards southern highlanders. In a February 1958 article for Harper's, "The Hillbillies Invade Chicago,"

Albert Votaw argued that "the city's toughest integration problem has nothing to do with Negroes" but, rather, "it involves a small army of white Protestant, Early American migrants from the South — who are usually proud, poor, primitive, and fast with a knife." At about the same time, television shows such as The Real McCoys, The Andy Griffith Show, and The Beverly Hillbillies played a significant role in shaping public perceptions and stereotypes about southern mountain people. Historically, middle-class economic interests had used the hillbilly image to "denigrate working-class southern whites (whether from the mountains or not) and to define the benefits of advanced civilization through negative counterexample . . .," argues historian Anthony Harkin. Since Cohen and his peers questioned and challenged the supposed benefits of modern civilization, Appalachia, to them, did not seem deviant or a land of hillbillies but instead a bastion of authenticity, a retreat from the commercialism of contemporary mass culture. And yet, while folk song collectors like Cohen longed to leave the city for the mountains, many in the mountains yearned for middle-class comfort and a steady city job.47Anthony Harkin, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 4 and 171-176. See also, J.W. Williamson, Hillbillyland: What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Kathleen M. Blee and Dwight B. Billings, "Where 'Bloodshed Is a Pastime': Mountain Feuds and Appalachian Stereotyping" and Sandra L. Ballard, "Where Did Hillbillies Come From? Tracing Sources of Comic Hillbilly Fool Literature," in Back Talk from Appalachia, 119-137 and 138-149; Horace Newcomb, "Appalachia on Television: Region as Symbol in American Popular Culture," Appalachian Journal 7 (Autumn-Winter 1979-80): 155-164.

Public responses to the 1960 Mountain Music of Kentucky release quickly revealed to Cohen the power that documentary and other media images carried. Folklorist D.K. Wilgus recognized the effort as one of the first to respectfully represent Kentucky folk music and life. "John Cohen's collection of Mountain Music of Kentucky is another raid on our resources by a 'furriner,'" Wilgus wrote, "but put away your long rifles, boys. We couldn't have asked for a more sympathetic interpreter than Cohen." An Appalachian journal, Mountain Life and Work, expressed similar sentiments by quickly assuring readers that Cohen's record was not another stereotyping of the region’s people and culture. "Anyone who is touchy about the subject of mountain people and music, as talked about or misconstrued by outsiders, will thank Mr. Cohen for a sympathetic, 'whole,' treatment of the music and people he met at Hazard and nearby," the reviewer wrote.48D.K.Wilgus, "On the Record," Kentucky Folklore Record, Vol. 6, No. 3 (July – September 1960): 96; Mountain Life and Work: Magazine of the Southern Mountains, Vol. 36, No. 3 (Fall 1960): 51.

Clip from Willie Chapman, "Little Birdie," Disc One, Mountain Music of Kentucky CD, Smithsonian Folkways CD 40077.