Overview

Using murder mysteries to address what she saw as destructive, rather than progressive, forces coming from the city into the countryside of north Fulton County, Georgia, journalist and fiction writer Celestine Sibley (1914–1999) attempted to present the city of Atlanta and the region beyond it as antithetical. Sibley's once beloved city had come to represent the forces of greed and capitalism encroaching upon what she viewed as the rural simplicity and goodness of country living. However, these novels in effect reveal the two ideologically separate spatial entities as connected within the broader economic processes of late-twentieth-century urban sprawl and within broader historical patterns of race relations in the Atlanta metropolitan region.

Introduction

|

| Roswell development, 2008 |

In her 1995 murder mystery, A Plague of Kinfolks, journalist and fiction writer Celestine Sibley (1914–1999) made her feelings clear about Atlanta's sprawl into the area near Roswell, Georgia, about twenty-five miles north of the city. When the book's protagonist, Kate Mulcay, attends a dinner party in the new neighboring subdivision named "Shining Waters," a fellow guest asks her opinion about paving nearby Loblolly Road. Kate explodes, launching into a diatribe about what the subdivision has done to the historical and natural area around her cabin: "'You are all new here,' she said, her voice carrying to the living room, bringing back those who had wandered that far. 'You mean well. I'm sure you are good people, but I think you are blind and misguided. You have taken so much, so damned much!'" (PK, 115).

Outraged by such intrusions of the city into her country, Kate adds that she will see the pro-paving residents of Shining Waters in hell before she allows them to destroy a road that had rich local significance (PK, 117). A Plague of Kinfolks's plot centers around Kate Mulcay's attempts to identify the person and the motivations behind an assault and two murders that occur near her home. By book's end, we have learned that the villains are none other than subdivision resident and dinner party host Bob Dunn and his mistress Charlene (who kills Dunn's wife with "a plain old lye-stained stick that was once used to beat the dirt out of work clothes on wash day") (PK, 198).

Here, as in two of her other books, Ah, Sweet Mystery (1991) and Spider in the Sink (1997), Sibley puts forth tropes of the bad developer and the turncoat local—more specifically, the avaricious white male entrepreneur, capitalizing on the phenomenon of sprawl, who will take whatever action is necessary to get what he wants (land and money) and the greedy, disloyal, longtime resident who will also do what is needed to turn his/her family land into a large, quick profit. Kate Mulcay emerges as the shero-sleuth in Sibley's mysteries. By the end of each, she has prevented these conspirators from succeeding, keeping out much of what she and other loyal residents see as destructive change. But, to take it a step further, Kate succeeds in maintaining a sense of the "country" as separate from, and antithetical to, the "city." That success can also be attributed to the interests of Sibley herself. Despite showing time and time again—in her newspaper columns and works of non-fiction from the 1960s to 80s, and in her mystery fiction in the 1990s—the interplay of country and city, especially in terms of land development and sprawl, Sibley generally conceived of the two as separate geographical and metaphorical entities. The values and ways of life of each stood in contrast to one another, with the country particularly representing a more traditional pastoral.1Raymond Williams and Leo Marx discuss this type of pastoral in their respective works, The Country and The City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) and The Machine in the Garden (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964).

|  |

While I discuss Sibley's use of the pastoral, this essay focuses on her mysteries set north of Atlanta and the critique of the "perils" of urban sprawl emerging from her fiction. Sibley seems unique as a southern writer in her choice of murder mysteries as the vehicle through which she could address what she saw as destructive, rather than progressive, forces coming from the city into the countryside of north Fulton County. Although not considered a "canonical woman writer" and rarely mentioned within literary discussions, Celestine Sibley was one of the most read writers in the southeastern United States during the last half of the twentieth century. Her columns—some ten-thousand during her career—appeared almost daily in the widely circulating Atlanta Constitution (the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, as of 2001), and she published twenty books, most under the guidance of her New York editor Larry Ashmead.2Ashmead was an editor at Doubleday, then at Simon & Schuster, and finally, at Harper & Row; Sibley followed him to each publishing house. Sibley's published works include: the semi-autobiographical novelsJincey (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978) and Children, My Children (New York: Harper & Row, 1981);Young'uns: A Celebration (New York: Harper & Row, 1982); her memoir, Turned Funny; six mysteries, The Malignant Heart (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1958), Ah, Sweet Mystery: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), Straight as an Arrow: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), A Plague of Kinfolks: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), and Spider in the Sink: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1997); two works on Atlanta, Peachtree Street U.S.A. (1963), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1986, and Dear Store: An Affectionate Portrait of Rich's (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1990; two books on her cabin in North Georgia, including A Place Called Sweet Apple: Country Living and Southern Recipes (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, and The Sweet Apple Gardening Book (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972); collections of her columns, including Christmas in Georgia (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Especially at Christmas (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Mothers Are Always Special (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Day by Day with Celestine Sibley (New York: Doubleday, 1975), Small Blessings (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977), For All Seasons (Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Publishers, 1984); and Tokens of Myself (Atlanta, GA: Longstreet Press, 1990). She also wrote the foreword to Peter Beney's collection of photographs titled Atlanta: A Brave and Beautiful City (Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd., 1986) and the text for The Magical Realm of Sallie Middleton (Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House, 1980). Note: I use parenthetical citations for page numbers from these novels and the following abbreviations for each book: ASM for Ah, Sweet Mystery; PK for A Plague of Kinfolks; SS for Spider in the Sink; and DH for Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle. But while Sibley was an urban reporter and columnist, whose career at the Constitution spanned fifty-eight years, she also lived for more than three decades in rural north Fulton County, in a log cabin she called Sweet Apple. After rearing her children in midtown Atlanta, she moved to Sweet Apple at age forty-nine, commuting daily to her work in downtown Atlanta from 1963 to 1999.

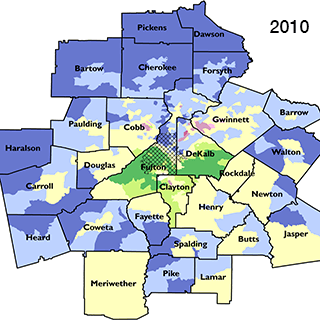

Celestine Sibley was by no means alone in her exodus from the city. From 1960 to 2000, the population of the metropolitan region grew from 1.5 to 4.5 million people, while the city's population declined from 487,000 to 416,000. The ring of suburbs just beyond the city increased in population during this time from 326,000 to just over one million people during that forty-year period, with the second ring of suburbs, including Sibley's area of north Fulton County, dramatically increasing from 334,000 to just over 2.2 million people.3"Atlanta Metropolitan Growth Since 1960," http://demographia.com/db-atl1960.htm (accessed January 10, 2009). Such changes coincided with changes in the racial make-up of Atlanta as well and the phenomenon of white flight during the 1960s. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the white population of Atlanta decreased by 170,000 people with the city's population becoming majority black by 1970. Responding in part to the desegregation of public schools and facilities, white Atlantans fled to the city's suburban rings that came to comprise the metropolitan area. In recent decades, those suburban rings have seen significant growth in their black populations, though Sibley's area of north Fulton County remained predominately white.4My thanks to an anonymous Southern Spaces editorial reviewer for pointing me to these demographic trends and their connection to Sibley's move from midtown Atlanta to north Fulton County. See generally Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007) and Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

The nineteen boxes of "fan mail" in the Emory University archives—containing thousands of letters sent to Celestine Sibley throughout her career—attest to her popularity, especially among white readers as I will discuss later, in and beyond Atlanta. Readers' letters provide a strong sense of a changing Atlanta and Deep South since World War II, and examining them in greater detail would make for an interesting analysis of this time period. Here, however, I concentrate primarily on Sibley's thick descriptions of the area around Sweet Apple and the ways she inadvertently complicates her own city-country binary through a focus on sprawl and development, a process that in and of itself involves an infusion of city into country and vice versa. Sibley approaches the pastoral ideal of "the country" that emphasizes the "peace, innocence, and simple virtue" of rural life, in contrast to the city "as a place of noise, worldliness and ambition." Sibley imagines the city as "an achieved centre: of learning, communication, light," though she resists fully imagining the country "as a place of backwardness, ignorance, limitation." She nevertheless shows the country as removed from the capitalist forces in the city.5Williams, 1. But as Raymond Williams and contemporary feminist geographer Doreen Massey have argued, the dichotomy of country and city (local and global, for Massey) is false, as the two are always interconnected and mutually constituted— something that Sibley's writing demonstrates even as she appears to want to keep the two apart.

|

| Celestine Sibley in the garden at Sweet Apple, 1970 |

Sibley's pastoral is rooted in an older conception of place than the "anti-essentialist construction" of place defined and claimed by cultural geographers.6Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 121. But Massey's take on how place has traditionally been defined helps us better understand what is at work in Sibley's literary construction of Sweet Apple. Sibley's writing on her cabin involves a fixing of place that represents an "attempt" to "stabilize the meaning of particular envelopes of space-time." Sibley holds what Massey describes as a "view of place as bounded, as in various ways a site of an authenticity, as singular, fixed and unproblematic in its identity."7Ibid., 5. Italics in original. That "sense of place" can be understood "as an evasion; as a retreat from the (actually unavoidable) dynamic and change of 'real life.'"8Ibid., 151.

Massey's argument helps make sense of Sibley's imagined "country" as providing stability to white readers during a period of changing race relations—including desegregation of schools and public facilities in the 1960s, the growing Civil Rights Movement (in large part spearheaded by Atlanta's Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.), and the shift of city leadership to an African American mayor in 1973—and during the city's dramatic spatial expansion upward and outward. Letters from Sibley's readers make clear that her writing was appealing because it spoke to shared conceptions of place. During a period in which the countryside was becoming suburbanized, I believe her work stabilized place for white readers during a tumultuous period in Atlanta's history and stabilized place for herself during a time of her own difficult personal struggles.

Sibley's stabilizing work is reminiscent of late-nineteenth-century regional fiction. As Stephanie Foote contends in her discussion of local color fiction from 1870 to 1900, "regional writing developed strategies to transform rather than passively resist the meaning of the social and economic developments of late-nineteenth-century urban life." In effect, this "short-lived form," she argues, helped urban dwellers deal with their feelings toward the increase in immigration and imperialism at that time.9Stephanie Foote, Regional Fictions: Culture and Identity in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 3-6, 13-14. One need only think of the late-nineteenth-century Atlanta Constitution writer Joel Chandler Harris, author of the Uncle Remus Tales and other works that in part painted a rosy picture of antebellum plantation days. Reminding readers of a seemingly "simpler" time when racial roles were clear and defined, Harris's works brought some nostalgic solace to white southerners anxious about the potential social changes that came with slaves' emancipation. In a somewhat similar fashion, Sibley's writing provided a suburban imaginary that comforted white readers as the Civil Rights Movement challenged white, southern social norms and as Atlanta underwent unprecedented growth. The places in the "country" north of Atlanta that Sibley imagines in her later fiction are populated exclusively by whites; African American characters rarely appear in these novels. When they do, their "place" appears to be within predominantly black neighborhoods near downtown Atlanta, even more specifically in areas that historically have housed the majority of African Americans, such as southwest Atlanta.10For a rich discussion of the development and growth of these neighborhoods on the western, southwestern, and southern edges of the city of Atlanta from World War II forward, see Andrew Wiese's talk, "African American Suburban Development in Atlanta," Southern Spaces, http://www.southernspaces.org/2006/african-american-suburban-development-atlanta (accessed January 10, 2009).

It's not too difficult to determine Sibley's predominant readership or likely fan base. In letters, readers rarely identify by race—more often by age, location, or occupation. Of the hundreds of letters that I sampled, two writers in the 1950s identified as "colored," while I found no letter writers who openly identified as white. But it is abundantly clear that when Sibley wrote of "Atlanta," she almost always meant white Atlanta.11One exception to this is Sibley's chapter on African Americans in a chapter from Peachtree Street U.S.A., entitled "The Darker Third." As Massey reminds us, the search for "a place-called-home" is typically "a predominately white/First World take on things."12Massey, 165-66. Massey argues that the effects of globalization in the later part of the twentieth century "have undermined an older sense of a 'place-called-home,' and left us placeless and disorientated" (163), which helps to explain people's searches for rooted-ness. Even if Sibley had a significant number of African American fans, her depiction of Atlanta and her search for what Massey calls "a place-called-home" during times of dramatic social change is that of a white southerner of her generation coping with racial change and, later, with the effects of a city's transformation into a metropolitan region. I do not doubt that her columns in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution attracted a diversity of readers: she was, after all, a fixture in that paper for half a century and appears to have been a counselor and benefactor for a number of Atlanta's downtrodden, black and white alike, even while dealing with her own personal and financial hardships. Even so, the places she constructs in her fiction, at least in her later work, are spaces of whiteness and white nostalgia.

| Celestine Sibley's Sweet Apple cabin, 2008 |

Sibley constructs the pastoral in her earlier non-fiction through descriptions of her cabin—which she once described as her "little slant-roofed house with the rickety screen door that needs to be replaced, the grass that's a week past cutting, the window boxes that need watering"—and the quaint, simple locals who used to get their mail at the crossroads or who rarely went to the city because, according to a woman Sibley knew, "'Hit's too fur to walk and cars jiggle you so bad.'"13Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple, 57-58; Sibley, Tokens of Myself, 15. (This column originally appeared on October 11, 1983.) But she later seems to acknowledge the interconnectedness between the country and the city, as suburban sprawl began to more pervasively disturb the idyll of her log-cabin lifestyle—specifically in the form of a new subdivision developed near her property. Her mystery novels also served to displace anger felt towards former "city" dwellers whose newly built homes encroached upon her protagonist's "country." In books such as A Plague of Kinfolks, urban sprawl enmeshes country and city within the same money-driven pattern. Still, Sibley seeks to maintain the separation, as the principal villains in her fiction turn out to be newly-arrived residents of the subdivision, greedy developers, or local accomplices who grew up in the previously "undeveloped" countryside. The latter turn out to be exceptional turncoats in an otherwise "loyal" and tight-knit rural community.

Merthiolate-Colored Flags

Sibley's locating Sweet Apple within the pastoral was as much a personal maneuver as a public one. Real and imagined country living brought Sibley comfort following a tumultuous marriage and the sudden death of her husband, which left her the single parent of three children. With Sweet Apple came an idealized rustic simplicity and natural harmony that had been missing from her life. In her autobiography, Sibley candidly and unashamedly discusses her rocky marriage and recounts how the excessive drinking of her husband, Jim Little, cost him job after job.14Sibley claims that his boss at the AP shattered his confidence in the early 1940s, and an offer was made to Celestine to switch jobs with her husband. She declined, and Little was fired. He took a job at theJacksonville Journal while Sibley stayed in Atlanta with the kids. When Sibley considered quitting theConstitution to join him in Florida, Ralph McGill offered to hire Jim. In August 1943, Sibley gave birth to their third child, Mary. Little was fired from the paper before Celestine's pregnancy was known, and he went to work at the Bell Aircraft bomber plant editing their publications. He continued to drink heavily, and he began to have an affair with a woman he met at the plant, calling it off only after Sibley confronted him. Sibley, Turned Funny, 119-23. During this period of roughly fifteen years, Sibley worked full-time at the Atlanta Constitution, part-time for the Northside News, wrote anything she could get paid for (including "torrid adventures for confessional magazines"), and rented out rooms to help pay the mortgage on the house she had purchased on Thirteenth Street.15Sibley, Turned Funny, 147-48. The play Turned Funny, adapted from Sibley's memoir, implies that Ralph McGill offered her a column as a way to prevent her from having to contribute to confessional magazines for extra money. Phillip DePoy wrote the play, which had its debut under the direction of Fred Chappell at the Theatre in the Square in Marietta, Georgia, August 6-September 24, 2006. The Constitution and Journal came under common ownership in 1950, and she was offered additional pay for writing pieces about Hollywood for the paper's Sunday magazine.16Turned Funny, 166-67. The Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution came under common ownership in June 1950, when James M. Cox purchased the Constitution. "The Constitution continued as a morning paper with a liberal editorial bent, while the afternoon Journal had a more conservative leaning," states the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The two papers combined newsroom staffs in 1982, but did not officially merge into theJournal-Constitution until 2001. The New Georgia Encyclopedia, s.v. "Atlanta Journal-Constitution," http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.com/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1807&sug=y (accessed September 29, 2006).

| Celestine Sibley and grandson in Sweet Apple kitchen, ca. 1970s |

Sibley reared their three children while Little's drinking and misbehaving intensified. (He died from a stroke in 1953 at age forty-five.)17Turned Funny, 177-78. Sibley was, in effect, always a single mother relying on her mother and housekeepers while she worked. She was not always aware of, or privy to, the social lives of her children, who came of age in the late 1950s and early 1960s. From Sibley's semi-autobiographical novel Children, My Children and her granddaughter Sibley Fleming's book, we know the most about the heartaches that Celestine Sibley experienced with her daughter Mary Everitt Little (Fleming), who became pregnant at age seventeen and eloped with the baby's father, Cricket Fleming. The baby, a son named Richard, died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome only a few months after his birth.18Mary seems to have been a somewhat unpredictable young woman. In 1965, for example, she ran away to Montgomery, Alabama, to join in the March to Selma. Upon learning of Mary's flight, Sibley called Martin Luther King and asked him the personal favor of having one of his lieutenants escort her back to Atlanta, which he did. Sibley wrote in 1968 that upon hearing of his assassination, she realized she had never thanked him. Celestine Sibley, "In the Rain by a Mississippi Truck Stop," Atlanta Constitution, April 9, 1968. Letters between Sibley and her New York editor, Larry Ashmead, also indicate that Mary had forged checks on her mother's account in the 1970s. The young couple had two more children, Bird and Sibley, and the family moved often due to Cricket's career as a jazz musician. According to Sibley Fleming, her parents never had money and would regularly leave her and her brother with Celestine for extended periods of time. Cricket seemed to resent Celestine's role in his children's lives, even though she regularly supplied the family with groceries and school clothes.19Celestine Sibley Fleming and Sibley Fleming. Celestine Sibley: A Granddaughter's Reminiscence(Athens, Georgia: Hill Street Press, 2000), 28-29. As Celestine Sibley recounts, Cricket kidnapped the two children in 1976. Celestine helped Mary hire detectives and a lawyer to track them down, even going on a stake-out in New Orleans.20Sibley, Turned Funny, 258. The children had gone to live with Cricket's parents in Indiana and neither Mary nor Celestine saw them again until the mid-1980s.21Celestine was convinced that the children had been brainwashed, and she believed that Mary was an innocent victim of Cricket's irrational behavior. Sibley Fleming provides a somewhat different account of that period of her childhood. Fleming claims that her mother drank excessively (which Celestine also alludes to in the fictional character of Leslie in Children, My Children) and that she threatened suicide in front of Fleming and her brother. She was at times abusive, especially when she thought that Cricket was having an affair. After moving to New Harmony, Indiana, to live with their paternal grandparents, they told their father that they wanted to talk to Celestine. He would allow it, but he said that they had to tell Sibley what Mary was like as a mother. When they did, claims Fleming, Celestine refused to believe them. But Sibley had always been the one who came to their rescue. For example, when Fleming's Uncle Jimmy, Celestine's first born, allegedly molested her one night when Celestine was out of town, Celestine immediately sent money to pay for a bus ticket to get Jimmy out of their house. Despite the protection Celestine Sibley had always given her grandchildren, she failed to believe their assessment of their mother—her daughter—as unfit, which in turn pushed those children further away. Fleming, Celestine, 55-65. Two letters to Celestine Sibley from her editor, Larry Ashmead, suggest that she had told him about her concern over Jimmy. Ashmead wrote in July 1975 that Jimmy is "so nice and so bright and my heart hurts for his lack of motivation and utilization"; a month later, he cryptically wrote to Sibley that "it is best for Jimmy" but that he understood "it" had caused her to feel low. Larry Ashmead to Celestine Sibley, July 16, 1975 and August 8, 1975, Box 2, Folder 8, Celestine Sibley Papers, MARBL, Woodruff Library, Emory University. Sibley Fleming—after a move to Ireland, a marriage, and the birth of a son in 1985—returned to Atlanta with her family and became her grandmother's assistant.22Sibley, Turned Funny, 270. In her novel, Children, My Children, a book Sibley allegedly wrote to pay for the detectives and lawyers hired to locate her grandchildren, Celestine tells a similar tale, portraying in rich detail the emotional turmoil experienced by the grandmother-protagonist Sally. She also depicts Sally's daughter Leslie as a genuinely caring and devoted mother, though not someone who is always forthright about her troubled relationship with the children's father.

Sweet Apple offered Sibley a space of retreat during tumultuous times in her personal life; its construction in print offered urban, mostly white, readers temporary reprieve from Atlanta's stresses and conflicts. Amid familial chaos and Atlanta's sprawl, Sibley continuously clung to pastoral ideals of her disappearing countryside. Twenty years after moving to Sweet Apple, urban sprawl stretched into Sibley's backyard.23Jack Strong, Sibley's longtime partner who eventually became her second husband, introduced her to Sweet Apple. In search of some land in the country in 1961, he had found a man named Doc Smellie who "dabbled a bit in real estate" to show him some areas in northern Fulton County one Saturday afternoon. Doc took them by a dilapidated log cabin, dating to the early 1840s, that had once served as a schoolhouse for local residents. Instantly enamored, Sibley bought the cabin and the acre of land on which it stood for $1,000, and Jack purchased the twenty acres nearby. She sold her house on Thirteenth Street, rented an apartment while the renovation of Sweet Apple was completed, and finally moved to the cabin in 1963. Sibley, Turned Funny, 204. Sibley chronicles the renovation process in the beginning of A Place Called Sweet Apple (1967). She began using her column to comment on the invasion of her Sweet Apple space and the desecration of natural surroundings, soothed only by her work at the Constitution and domestic life in the cabin. As the bulldozers encroached in the 1980s—signaling suburban subdivisions, strip malls, and businesses to Roswell—her resistance to Atlanta's growth intensified as her appreciation of urban development ambition waned.24Elsewhere I discuss at greater length Sibley's genuine love of and appreciation for the city of Atlanta, arguing in fact that she crafts Atlanta as "urban pastoral" in her writing. See Margaret T. McGehee, "On Margaret Mitchell's Grave: Women Writing Modern Atlanta" (PhD diss., Emory University, 2007). Others seemed to share her opinions. Carole Ashkinaze wrote that Sibley's Sweet Apple columns had a "vast following" that made "'Generation X' editors from other parts of the country. . . scratch their heads."25Carole Ashkinaze, "Celestine Sibley: Gone But Not Forgotten," The Southerner, http://www.southerner.net/v1n4_99/passing4a.html (accessed January 12, 2004). In an era of increased urbanization and globalization, those editors were no doubt surprised by the continued appeal of one columnist's nostalgic musings to such a large number of urban readers.

|

| Celestine Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple |

In A Place Called Sweet Apple (1967), Sibley wrote that when she first saw the cabin, she was "a content/ city dweller," proud that in her more than fifteen years of living in midtown Atlanta, she had reared her children "without putting in long hours chauffeuring them to school, the Brownies, the library, dancing class or the piano teacher. They could walk or ride the bus everywhere they had to go."26Celestine Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple, 17. A 1967 article written by Sibley's friend Wylly Folk St. John (who came to work at the Atlanta Journal the same year that Sibley arrived at the Constitution) details Sweet Apple, describing the "10,000 hours of personal labors-of-love" that Sibley and others put into the cabin's renovation. Wylly Folk St. John, "Celestine Sibley's Sweet Apple Cabin," The Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine, November 5, 1967, 8+. In the city, her kids had all the benefits of living in what Raymond Williams describes as "an achieved centre"—education, social and cultural opportunities, mass transportation. The implication is that such things were not present in the area around Sweet Apple, but it did not take Sibley long to become a content/ country dweller. For Sibley, Sweet Apple was "not really a settlement but a state of mind."27Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple, 51.

It "may be a place shaped by memory and fleshed out by nostalgia," Sibley wrote, "but some of us believe in it."28Ibid., 59. For urban readers, Sibley crafted a spot where time appeared to stand still, where antiquated agrarian traditions like barn raisings and corn shuckings continued to thrive.29Ibid., 58. Sibley regularly contrasted urban and rural life in ways that reified the connection of the rural to nature. In describing the difference between kitchen windows, Sibley wrote: "A city kitchen window sill can retain its austere order year 'round. Suburban kitchen window sills change little, particularly if they're the new style facing the street with a wide swatch of picture-window glass above them . . . In the country the kitchen window sill is a catchall, a laboratory, a treasure cache."30Sibley, Ibid, 84.

|

| Clearing logs in development near Sweet Apple, 2008 |

In response to a reader who had asked if "in this convenience and comfort-laden twentieth century . . . there is any difference in life thirty miles from a big city," Sibley recounted how she had awakened one night to find a snake peering in her window and how a bird had built a nest within her bathroom vent pipe.31Ibid., 63-64. "How long," she asked in a 1986 column "can catnip hold out against bulldozers?"32Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 22, 1999 (originally appeared on June 6, 1986). While Sibley portrays the people of the Sweet Apple area as isolated from the city, many were, like herself, connected to Atlanta, through jobs, consumerism, media, and the expanding highway system. In its networks of circulation, the AJC not only connected Atlanta to its suburbs and beyond, but joined the Atlanta region to national and global events. The bulldozers in her backyard signaled inevitable expansion, forcing Sibley to confront the Atlanta growth she once had praised.

"Clamor has come to the country," she wrote in 1980. "Cars and motorcycles and trucks of all sizes and purposes roar by on our dirt road. Power saws whine through the afternoons."33Sibley, Tokens of Myself, 129. This column originally appeared on April 8, 1980. Suburban subdivisions—"with a cutesy-country name and a fresh cut split rail fence, not because it's the only kind of fencing available as in the old days in the mountains but because it is now country chic"—had begun to invade the place she called home and to disrupt the calm of her Sweet Apple retreat.34Ibid. "When it rains and the bulldozers are quiet we savor the tranquility," Sibley claimed. "One more day we have of country stillness, one more night when the moon can shine unchallenged by street lights."35Ibid., 130. In the afterword to the 1985 revised edition of her 1967 book A Place Called Sweet Apple, Sibley bemoans:

A few years ago little Merthiolate-colored flags showed up on stakes in what we had come to regard as "our" woods, heralding the approach of suburbia. Now paved streets, with electric lights at the corners and city water plugs marching alongside, crisscross the old pastures and fields and pierce the wooded hills. Splendid stone chalets, Victorian mansions and English manor houses have risen on the slopes and in the hollows.

Where I once gathered wild persimmons and blackberries, newcomers have put in swimming pools and tennis courts. Where we once heard Denver Cox gee-hawing his mule as he plowed his cornfield, we now hear hammer blows, power saws and bulldozers clearing sites for still more building. Many of the cherished landmarks are gone. The secret woodland spots we regarded as our own private hideaways…are now open and owned, the property of newcomers who, in all probability, love them too, and may show it by having them landscaped.36Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple (1986), 235.

Using words like "marching" and "pierce," Sibley depicts these suburban developments as invading and ravaging the natural landscape of her area. The large houses—imitations of the estates of both the British and the Buckhead elite—and the landscaped yards suggest an imposition of order upon the natural, undeveloped land.

| Private residence in Roswell development, 2008 |

It would be easy to dismiss Sibley as one more link in a chain of pastoral writers longing for "the way things used to be"—before the train, or the bulldozer. But as I described earlier, what distinguishes her is the genre through which her critique comes—the murder mystery. Sibley infuses this popular and entertaining genre with the serious critique of development. Several of the murder mysteries written by "the Agatha Christie of Roswell" feature villains who are suburban real estate entrepreneurs or who reside in or near the fictional subdivision of Shining Waters.37Larry Ashmead told Sibley in a 1989 letter that he and literary agent Helen Pratt had "talked about how we're going to make you the Agatha Christie of Roswell." Larry Ashmead to Celestine Sibley, 1989, Box 25 (unprocessed), unnumbered folder of correspondence from Larry Ashmead, Celestine Sibley Papers, MARBL, Woodruff Library, Emory University. In many ways, a murder mystery serves as an ideal vehicle for such critique, given the basic binaries of good vs. evil and hero vs. villain at the core of the subgenre. Such binaries, in Sibley's case, nicely dovetail with the country vs. city dichotomy underlying her prose.

The Country of Mystery

Sibley published her first murder mystery, The Malignant Heart, in 1958, but did not return to the genre until thirty-three years later. In this novel, she introduces readers to Katherine (Kate) Kincaid, a young reporter for the Atlanta Searchlight and an amateur sleuth who lives with her father, a retired policeman. Kate appears to be one of the few female news reporters on staff; most of the other women staffers work in the "Casserole and Camisole Department," writing, as most newspaperwomen did at that time, about fashion, food, gardens, club activities, and high society.38For a discussion of "women's pages" as related to newspapers' evolving understanding of "lifestyles," see Patrick T. Wehner's "Living in Style: Marketing, Media, and the Discovery of Lifestyles" (PhD diss., Emory University, 2000).

Resembling Sibley, the fictional Kate "wrote a column a few days a week, covered an occasional story. . . and was available as a kind of office memory for youngsters who knew nothing about Atlanta's or the newspaper's past."39Sibley, Ah, Sweet Mystery, 25. When we meet her again in Ah, Sweet Mystery (1991), the widowed Kate Mulcay lives in north Fulton County in a cabin that she and her late husband Benjy restored. In her late forties to early fifties, Kate still reports for the Searchlight but also writes a regular column.40Although Kate's age is never clear, she notes in Spider in the Sink that the new minister in the area, age forty-five, is "only a few years her junior," 11. In Dire Happenings, we learn that she and her husband had lived in the log cabin twenty years prior to his death. It's never clear how long he has been gone. If the time of the book's setting corresponds to the time of its publication and if Kate had been in her mid- to late-twenties in The Malignant Heart, published in 1958, Kate would be in her mid- to late-sixties by 1997, the publication date forSpider in the Sink.

Though "an old society editor" had told Kate "that nobody, but nobody, lived beyond the perimeter of Atlanta," the encircling Interstate 285, and though "[s]ociety's folklore decreed that you live within the circular boundaries of the big eight-lane highways which encompassed the city," Kate chose to break from "society" for a life in the woods (SS, 60) and committed to making the daily commute "in bumper-to-bumper traffic that was beginning to spill over onto the old country road" (ASM, 2). In Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle (1993), we learn that Kate covered the Georgia General Assembly as a reporter until her editor reassigns her to write a regular column, replacing her with "a lanky kid newly graduated from the University of Georgia's journalism school" (DH, 2). In Spider in the Sink (1997), we get more details on the forty years that have passed since the events of The Malignant Heart. Benjy and Kate had lived with her father in the early years of the marriage in a "clapboard cottage" in downtown Atlanta. In what would probably have been the early to mid-1960s, the city started to purchase areas of their neighborhood to turn into a parking lot for the new baseball stadium. After Kate's father died from a stroke, and "by the time the bulldozers were on their street," Kate and Benjy "were ready to move anyhow" (SS, 40). Kate's cabin—with "its raddled roof, its vacant lopsided window openings"—had won her affection the first time she and Benjy had seen it and had brought much happiness to them, "although both were city-reared" (ASM, 14).

| Sibley's Commute: From Sweet Apple to Atlanta. A short film by Mary Battle, 2008. |

Almost all of Sibley's later mysteries speak to land development in northern Georgia. In those mysteries, the villains turn out to be greedy capitalists. Take Ah, Sweet Mystery, in which someone has murdered local resident Garney Wilcox, "a mean avaricious jerk who was ruining the countryside with his real estate 'developments'—what a misleading word!—and breaking his mother's heart" (ASM, 3). In A Plague of Kinfolks (1995), the culprit responsible for beating eccentric local Mr. Renty, the murderer of Bets Dunn (wife of subdivision resident Bob Dunn), and the driver in a hit-and-run that kills a local teenager turns out to be Mr. Renty's niece and Bob Dunn's mistress, Charlene. Mr. Renty, we learn, owns "hundreds of acres" in north Fulton and Cherokee counties, land greatly coveted by subdivision developers. Driven to cash in on her uncle's potential profits to please Bob Dunn, Charlene tries to kill her uncle. Although unsuccessful, she does succeed in murdering two others.

These characters are also villainized through how they stand in contrast to the romanticized poor who have inhabited this country place for a century or longer. While Kate embraces home life in the north Fulton "wilderness," it is Miss Willie, Garney Wilcox's eighty-five-year-old stepmother, who embodies country living and stands as representative of the "folk" one finds in stereotypical local color. She is "everybody's best neighbor," we learn in A Plaque of Kinfolks, who "retained the flavor of the mountains in her speech, the love of mountain beauties in her heart" (ASM, 4). She epitomizes antiquated rural living, using an almanac to guide her planting and an iron pot and lye soap to wash her clothes. Miss Willie once sold butter, pound cakes, and vegetables in the nearby town of Roswell. At one moment in Spider in the Sink, she sits "by her fireplace, piecing together one of her interminable quilts by the light of the kerosene lamp" (SS, 54). Her old-timer ways, coupled with her dialect, make her into the lovable and endearing representative of the country. In her "earth-and-smoke smelling clothes" (ASM, 7), Miss Willie is the country and the ways of life that comprise it; any destruction of the area around her 140-year-old homeplace is a violation of Miss Willie herself.

The Shining Waters subdivision that separates Kate's cabin from Miss Willie's home stands in significant contrast to their rustic homes:

Streets and sidewalks and curbs replaced the road they had used. Now lights glowed back of French doors and stained-glass windows and the reproduction bubbly glass of twelve-over-twelve panes of saltboxes and southern colonials. One incongruously vibrant blue swimming pool had been lit up….But beyond them all the dark hulk of Cy Wilcox's hill rose, unpaved, unlandscaped, unlighted and unoccupied (ASM, 13).

What had once been pine woods with one old wagon road leading to the river when she and Benjy had first moved into the cabin were now paved streets lined with handsome half-million-dollar houses representing every kind of architecture Kate had ever seen, with the exception of log cabins and sharecroppers' shacks. There were French chalets, half-timbered stucco and brick, clapboard, and some new building material that Kate couldn't peg, but considered nonetheless splendid. She had never dreamed her own forest would be felled to make way for swimming pools and tennis courts and cunning little gazebos. (PK, 31-32)

"Country" and "city" sit side-by-side on the same geography. While Sibley may show them as connected within that landscape and within a broader economic network, the new house, with its "incongruously vibrant" pool, doesn't belong. Here, new money—made by former city residents who, in keeping with the notion of "city" as connected to education and enlightenment, include a judge, lawyer, and doctor (PK, 111)—has ushered in the illusions of luxury and the trappings of leisure. This subdivision "began just beyond a thin stand of pines and scraggly shrubs separating the backyards of the big new houses from the gravel road and mercifully screening from their view Kate's shabby old cabin" (ASM, 19). Having taken Shining Waters' name from nearby "Shine Creek" (once used in the illegal moonshine business), the developers "had robbed [the creek] of its history and corrupted it into prettiness" (ASM, 19).

The "chalets" of Shining Waters stand in significant contrast to the cabins and small homes built from local wood by their owners and inhabited by unschooled country folk like Miss Willie or Mr. Renty. At a dinner party held at the Dunns' Shining Waters residence, Kate makes clear her refusal to see her beloved country road paved. While Kate's obnoxious houseguest and cousin-by-marriage, Edge Green, assures fellow attendees that Kate is "for progress," she thinks to herself: "Progress is one of those Mother Hubbard words, covering everything and touching nothing. Progress is the most abused word in the English language. A word used by people who want to destroy" (PK, 113, italics in original). Kate is not so naïve as to think that change is avoidable, but she desperately longs to hold on to markers of the past.

Kate's cabin becomes a literal and figurative repository for the past. The material goods within that space, many of which she had purchased at yard sales or the Salvation Army, serve to evoke the past for her and for Sibley's readers—the "old pie safe," for example, or the "dime-store Fiesta ware" that had belonged to her mother (PK, 17). Furthermore, Kate has resisted making modern improvements to her living space. She has not installed much nighttime lighting around the cabin, keeping the area around the house "purposely dim because she did not want to capitulate to the pressure for streetlights and floodlights that the subdivision fostered." "A little light was a good thing," writes Sibley, "but too much light destroyed the illusion that she was in the country and dimmed the brilliance of the moon and stars." (PK, 23).

Still, Kate discovers that she likes some residents of Shining Waters, who, with the exception of the drug dealers she helps to put away, are "not only affluent, but friendly, law-abiding, well-mannered people" (PK, 32). They by no means compare, for Kate, to "characters" from the area's past like Mr. Banana Pierce, who had sold produce and planted numerous fruit trees in the area (PK, 32-33), but she does become increasingly tolerant of their presence over the course of Sibley's Kate Mulcay series. She admits a fondness for Bets Dunn, probably because of Bets' "interest in country history and her pleasure in the country" (PK, 89).

Like Sibley herself, Kate Mulcay also regularly expresses a selective appreciation for the city of Atlanta. On her way to the office one day, Kate "looked at [Buckhead] with pride." "Handsome hotels—the big Ritz-Carlton, malls with all the stylish and expensive stores, restaurants where she never ate anymore but which she was glad to see there. A cosmpolitan city, her Atlanta," writes Sibley (PK, 73). Kate is a fan of Atlanta's public transportation, MARTA, "exulting in the cleanliness of buses and trains, the lack of torn upholstery and graffiti that marred the systems she had seen in other cities" (PK, 74). Appreciating to some extent what Atlanta has become, she bemoans what it used to be and is no longer. We learn that Kate "loved Decatur Street" in downtown Atlanta, but what she loves is the area that once was filled with merchants like Mr. Walter Bailey from whom she "[s]ought wooden butter molds and cedar water bucket" (PK, 100-101). "It had been a shabby old street," writes Sibley, "of pawnshops, secondhand furniture stores, and catfish and pork chop restaurants. Used dresses and suits on hangers, hanging from doorways . . . A peanut roaster whistled in front of a hardware store" (PK, 100).41My thanks to an anonymous reviewer of this article who pointed out that in Sibley's discussion of the former commercial district, she "missed the opportunity to detail the ethnic diversity" that had characterized "old Decatur Street," including the presence of Jewish merchants who sold goods to black customers. This was Decatur Street before the arrival of Georgia State University, which she does recognize as an important addition to the city. "Only a moss-backed diehard would rather have the old Decatur Street than the new one with its library and science building and its beautifully landscaped entranceways," Sibley writes, "But it just wasn't interesting" (PK, 101).

This nostalgic yearning is characteristic of Sibley's writing. In crafting places seemingly removed from urban Atlanta, Sibley was able to create a "sense of place" that is connected to"memory, stasis and nostalgia," as Doreen Massey puts it (119). "'Place' was necessarily an essentialist concept which held within it the temptation of relapsing into past traditions, of sinking back into (what was interpreted as) the comfort of Being instead of forging ahead with the (assumed progressive) project of Becoming" (119). Tying Massey's ideas to what one finds in Sibley, we begin to understand her writing of place as a retreat from the changes occurring within her surrounding area and a return (or "relapse" or "sinking back into") what she deemed to be comfortable.

Paired with the nostalgic element in Sibley's writings were more subtle indications of grief and mourning—not quite melancholia, but still a profound sense of loss, a sense of something deeply precious having been taken away. The nostalgia that surfaces within Sibley's writing is to some extent racialized: a mourning characteristic of many postwar generation southern whites, men and women, who were not necessarily anti-civil rights or pro-segregation but who were locked in a certain "structure of feeling"—a certain emotional register—that produced ambivalence towards change. Sibley could, for instance, have generally liberal views but write place in a way that reinforced selective social—and particularly racial—divisions.

White Country, Black City

The imagined geography in Sibley's mysteries is primarily one of whiteness, and certain moments in these novels bring that whiteness into greater relief. In Ah, Sweet Mystery, set in the early 1990s, Kate accompanies the police on a drug raid in southwest Atlanta, specifically into the areas off of Interstate 20 around West End and the Atlanta University Center. This predominately African American area of Atlanta in Sibley's imagination is "dingy and dilapidated, growing more so as [Kate and the police] drew nearer to the expressway. Kate remembered when it was a respectable neighborhood, once grand, even, but gone now to seed." The area of southeast Atlanta, also primarily African American in terms of racial composition, is home to the federal penitentiary, "all around it poor, sad, neglected little houses with trash and garbage drifting over their yards" (ASM, 37).42According to Sibley's friend and fellow mystery writer, Kathy Trocheck, Celestine Sibley conducted research for this book by tagging along with Atlanta's Red Dog antidrug squad. Trocheck, untitled tribute to Celestine Sibley, in The Celestine Sibley Sampler, 37. These spaces bring about a "sense of melancholy for what [Kate] knew was there, or used to be, rather than what she saw" (ASM, 38). "Melancholy" here implies the sadness and grief resulting from an irrevocable loss—in this case, the loss of an ideal urban (and specifically inner-city) neighborhood.

| Techwood Homes, housing project in Atlanta, 1993. Site of Sibley's descriptions of urban decay in Ah, Sweet Mystery (1991). |

Troubled by what she finds in these areas (e.g., drug deals, trash lining the streets, children out alone after dark), Kate's thoughts drift to Atlanta's initial public housing projects built during the 1930s, Techwood Homes and University Homes, "virtual showplaces" that were the first of their kind in the nation. The present-day projects were "eyesores and hotbeds of drug traffic" that Kate feels should be dynamited, at the same time that she feels sympathy for the mothers and children who live within those areas (ASM, 49). In this moment, Sibley reveals the effects that earlier efforts of urban renewal have had on Atlanta's lower-income, African American populations who were pushed out of downtown from the 1960s forward in the name of progress.43For discussions of Atlanta's development and expansion in the last half of the twentieth century, see Clarence Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988 (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1989); Ronald H. Bayor, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); David Harmon, Beneath the Image of the Civil Rights Movement and Race Relations: Atlanta, Georgia, 1946-1981 (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996); Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta; Gary M. Pomerantz, Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn: The Saga of Two Families and the Making of Atlanta (New York: Scribner, 1996); Frederick Allen, Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City, 1940-1990 (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996); Harvey K. Newman, Southern Hospitality: Tourism and the Growth of Atlanta (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999); Larry Keating, Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001); and Kevin Kruse, White Flight (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). As Larry Keating describes in Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (2001), these groups have continued to be neglected, resulting in the formation of an underclass subject to substandard living conditions, higher rates of violence and crime, and continued residential segregation. Keating writes:

Atlanta's aggressively expanding economy is increasing, not closing gaps in income. Partly because a large portion of the city's African American population is living in poverty, the city has a disturbingly high crime rate. The city also has an inferior public-school system, which is both a consequence and a cause of pervasive black poverty. Misdirected economic development and substandard schools are primary reasons that so much of the city's black population is under-trained and underemployed, and black unemployment, in turn, contributes to the high crime rate. Until very recently, city leaders have done little to improve city's school system. They have put little effort and very little money into social-welfare and job-training programs. They have made only minimal efforts to revitalize low-income African American neighborhoods. And they have actually made living conditions worse for African Americans by destroying and failing to replace low-income housing in the downtown area…. Because black elected officials rarely advocate the interests of poor blacks, and because middle-class blacks have prospered in Atlanta's expanding economy, poor blacks are increasingly left out, increasingly isolated, and increasingly alienated.44Keating, Atlanta, 209-10.

Such spaces stand in contrast not only to the area around Kate's cabin but to other parts of white Atlanta as well. When Kate finds Jenny, her informant who lives in the housing project, beaten to death, the police take Jenny's clothes from Kate "without much interest." Earlier that day "a prominent northside woman had been throttled," and her case clearly took precedence in their minds. "Northside" here means the wealthy white area of town known as Buckhead. This woman "was the wife of an industrialist and had herself acquired a kind of reverential regard in town for her work with garden clubs and children's hospitals." In contrast, the narrator asks: "A little black woman whose claim to fame had been that she had been a wonder at doing fine laundry, what did her beating mean to them?" (ASM, 63).

Sibley's inclusion of Jenny's demise resonates with literary scholar Patricia Yaeger's commentary on "throwaway bodies." In studying southern women's writing, Yaeger observes, "we must pay attention to the difficult figure of the throwaway body—to women and men whose bodily harm does not matter enough to be registered or repressed—who are not symbolically central, who are looked over, looked through, who become a matter of public and private indifference—neither important enough to be disavowed nor part of white southern culture's dominant emotional economy."45Patricia Yaeger, Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing (University of Chicago Press, 2000), 68. Sibley brings into relief Jenny's plight and the indifference shown by Atlanta's leaders to Atlanta's lower-income, African American populations, and this signals her sympathetic understanding of racial dynamics and the neglect of black bodies in what former Mayor William Hartsfield once referred to as the "city too busy to hate." Jenny and her story nevertheless remain outside of Kate's—and other white Atlantan suburbanites'—geographies. In Sibley's work, urban becomes equated with black, while suburban/rural becomes synonymous with white. That racial-spatial dichotomy parallels the racial demographics of Atlanta today, a division resulting in great part from the impact of civil rights-era white flight in which white urbanites flocked to outlying towns and suburbs in fear of integration's impact on the city's public schools (and the impact on the social norms of previously segregated southern society).46See Kevin Kruse's White Flight for an extremely comprehensive account of white Atlantans' exodus from the city after World War II. The population of the city of Atlanta, as of 2000, was 61.4% Black or African American. US Census Bureau, Data set on race and ethnicity for Atlanta, Georgia, 2000 US Census, http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ QTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US1304000&-qr_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_QTP3&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U (accessed May 23, 2006).

In Sibley's imagined urban spaces, African Americans regularly appear as servants. Here again, white nostalgia infuses her conception of place, resulting in a reliance on stock characterization that suggests Sibley's allegiance to outmoded conceptions of southern blackness, including the mammy figure. When Kate goes to rescue a teenager from the Fulton County jail in Atlanta, she speaks to a black woman by the name of "Aunt Lucy." Aunt Lucy says to Kate, "'Mistis . . . Will you tell my peoples I'm here and ax 'em to come and get me?'" She then "recited a list of prominent Atlantans of another day, all of them dead now. 'Nussed their chillun,' she said softly. 'They come and get me'" (SS, 135). Her "peoples" here are white Atlantans, not her actual blood relatives (though given the history of interracial relationships in the South, who knows). Later, Aunt Lucy is referred to as "[a] black gentlewoman, the kind everybody in the South loved" (SS, 136). By relying on the mammy image and the figure of the "faithful slave" and by incorporating racialized dialect, Sibley pulls from an out-of-date, yet still all-too-familiar, cadre of black stereotypes and stock characters, including the gone-but-not-forgotten mammy.47For compelling and much more thorough discussions of this figure, see Micki McElya's Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007) and Kimberly Wallace-Sanders' Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008).

Black characters appear only in the heart of the city, not in the country where Kate resides.48An anonymous reviewer of this article confirmed what s/he termed "white myopia," stating that in her "imagined landscape," Sibley indeed failed to account for the African American farm workers and sharecroppers in rural north Fulton County at this time. But Kate's paternalistic attitude towards the black women she encounters is quite different from her attitude towards certain poor white characters. The villains in Sibley's mysteries, as mentioned earlier, are not always the newly arrived subdivison residents but also poor white locals who have become traitors because of their desire for money. In A Plague of Kinfolks, for example, Charlene—a former Dairy Queen employee described as "a chubby little woman with improbable blue-black hair teased into a tepee and wearing a purple bikini holding an overflow of white thighs together" (PK, 46)—attempts to kill her uncle because he owns land worth millions to developers. She does kill Bets Dunn to secure her place in Bob Dunn's life and in his Shining Waters mansion. The desire to move up the social ladder corrupts, and she is cast as an unattractive, no-good character.

Charlene in fact emerges as an example of what writer Dorothy Allison has described as the "bad poor."49See Dorothy Allison, Skin: Talking about Sex, Class, and Literature (Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1994). Allison writes that the good poor are imagined to be "hard-working, ragged but clean, and intrinsically honorable," personified in Sibley's fiction by the character of Miss Willie. The bad poor, a category to which Allison understood her family belonged, consisted of "men who drank and couldn't keep a job; women, invariably pregnant before marriage, who quickly became worn, fat, and old from working too many hours and bearing too many children; and children with runny noses, watery eyes, and the wrong attitudes."50Ibid, 18. We have echoes here of Yaeger's throwaway bodies; if "bad poor" and "white trash" are to be understood as virtually synonymous, then the bad poor are indeed throwaway bodies. Sibley easily dispenses with Charlene as she has failed to show the qualities that might redeem her as a valuable member of the community. Miss Willie, on the other hand, emerges repeatedly as an honorable, hard-working, and generous neighbor. From this contrast and other such moments in Sibley's mysteries, described above, the "country" emerges as a place shaped by particular racial and class parameters defining who does and does not belong.

Conclusion

| Celestine Sibley at Sweet Apple, ca. 1970s |

Celestine Sibley died in 1999 at her beach retreat on Dog Island, Florida, which she built with her second husband, Jack Strong. In the four years prior to her death, she had had several setbacks to her health, including breast cancer in 1995, for which she had a mastectomy and chemotherapy, and a heart attack in 1997. In 1998, she was told that the cancer had spread throughout her body and into her bones.51"Sibley Milestones," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 22, 1999. The day following her death, a cartoon by the AJC's political cartoonist Mike Luckovich appeared in the paper, showing a tall, somewhat disheveled woman in a baggy sweater and skirt standing at the pearly gates. Gatekeeper St. Peter says to his assistant, "Wait 'til Celestine sees the cabin we built for her. . . ."52Mike Luckovich, untitled cartoon, Atlanta Constitution, August 17, 1999. For her readers, Sweet Apple had been a rural place beyond the bustling city of Atlanta where they could travel in their imaginations; for Sibley, it had always been her place of refuge, her heaven, the home she clung to even as the bulldozers of urban sprawl groaned close to her backyard.

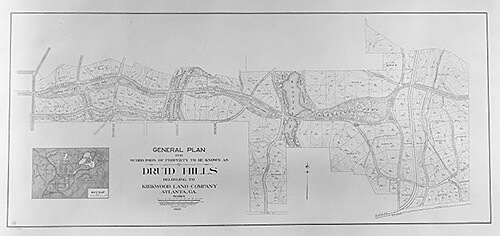

| Aerial map of area around Sweet Apple, 2002 (Sweet Apple cabin marked by red dot) |

On an aerial map of contemporary Sweet Apple, you can't miss the expansive roofs of the houses (and the azure spots of their backyard pools) located around her home. In the area surrounding her cabin sprawl numerous developments and high-end subdivisions not unlike Shining Waters, with names like Litchfield Hundred, Lakeside at Ansley, Overlook at Litchfield, and King Estates Manor. Litchfield Hundred's website describes it as "a private swim/tennis community" with "nearly 200 homes on acre-plus lots."53Litchfield Hundred, http://litchfieldhundred.com/outside_frame.asp (accessed February 20, 2007). According to a realtor's website, Litchfield Hundred's homes were built between 1986 and 2006, suggesting that this development may have served as inspiration for the imagined Shining Waters subdivision in Sibley's mystery novels.54Cathy Meder, "Roswell Homes and Subdivisions," http://www.cathymeder.com/Nav.aspx/Page=%2fPageManager%2fDefault.aspx%2fPageID%3d1557869 (accessed February 20, 2007). One entrance to this "community" is located adjacent to the road on which Sweet Apple sits, about a hundred yards from the cabin's mailbox. But the development spans the area around Sibley's former home, with a second entrance about a mile east on the principal thoroughfare of Cox Road. Half a mile down Lackey Road from Sweet Apple is the not-yet-completed, gated community of Overlook at Litchfield, a development whose sign advertises homes in the $900,000s; its website claims that many of these "large, executive residences" were built by builders "who made Lakeside at Ansley so popular."55http://www.chathamlegacy.com/newhome/overlook/index.asp (accessed June 10, 2008). King Estates Manor, as of June 10, 2008, offers homes on one-plus acres priced at $1,599,000 (5 bedrooms, 7 bathrooms) and $3.4 million (6 bedrooms, 10 bathrooms).56http://kingestatesmanor.net/10497/dsp_agent_page.php/53580/King_Estates_ Manor_Offerings/King_Estate_Manor_Offerings (accessed June 10, 2008). Lakeside at Ansley's online "tour" includes marketing photos of an ethnically diverse population enjoying life in their subdivision, suggesting that even if that diversity is not present, it can at least be imagined for that subdivision—and perhaps more broadly for the region.57http://www.lakesideatansley.com (accessed June 10, 2008). The racial demography for the city of Roswell, as of 2000, was 81.5% white, 10.6% Hispanic or Latino, 8.5% black, 3.7% Asian, 1.9% reporting 2 or more races, and .2% American Indian or Alaska Native. US Census Bureau, State and County Quick Facts for Roswell, Georgia, 2000 US Census, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/13/1367284.html (accessed August 4, 2008).

| Suburban Development: Roswell, Georgia 2008. A short film by Mary Battle, 2008. |

Bulldozers, piles of dirt, and massive houses have filled in this landscape, with Sibley's cabin and a few small neighboring houses the final holdouts to the surrounding, gigantic developments. Owned by Sibley's family, with her daughter Susan and son-in-law Edward Bazemore living there half the year, the sturdy cabin remains, for now, planted among the trees as "the developers still swarm around like vultures" (to quote Mrs. Bazemore), less than a mile away. One cannot help but wonder what will become of Sibley's home. Will it remain a part-time residence for her family in the decades to come? Will it evolve into an historic home and tourist site that reminds visitors of "the way things used to be," similar to Joel Chandler Harris's Wren's Nest in Atlanta's West End? Will Sweet Apple continue to be surrounded by residential and commercial developments? In the current economic downturn, as residential developments are put on hold across the United States, Sweet Apple seems safe from intrusion. But the bulldozer will no doubt rise again.

Acknowledgments

My deepest thanks to Dr. Allen Tullos for his sound advice and guidance on this article, to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments, and to Mary Battle for devoting countless hours to making this article more readable and much prettier and for enthusiastically traveling with me to Sweet Apple, camera in hand.

Recommended Resources

Print Materials

Allen, Frederick. Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City, 1940-1990. Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996.

Bayor, Ronald H. Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Bisher, Furman, Tom Bennet and Celestine Sibley. Atlanta's Half-Century: As Seen Through the Eyes of Columnists Furman Bisher and Celestine Sibley. Longstreet Press, 1997.

Duffy, Kevin. "Metro Atlanta's empty lots suffer neglect." Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 4 June 2008.

Fleming, Sibley. Celestine Sibley: A Granddaughter's Reminiscence. Athens, GA: Hill Street Press, 2000.

Harmon, David. Beneath the Image of the Civil Rights Movement and Race Relations: Atlanta, Georgia, 1946-1981. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996.

Keating, Larry. Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001.

Kruse, Kevin M. Kruse. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Lassiter, Matthew D. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Newman, Harvey K. Southern Hospitality: Tourism and the Growth of Atlanta. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Pomerantz, Gary M. Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn: The Saga of Two Families and the Making of Atlanta. New York: Scribner, 1996.

Sibley, Celestine. A Place Called Sweet Apple: Country Living and Southern Recipes. Atlanta: Peachtree Publishers, 1985.

———. A Plague of Kinfolks: A Kate Mulcay Mystery. Waterville, ME: Thorndike Press, 1995.

———. Ah, Sweet Mystery. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

———.Children, My Children. New York: Harper & Row, 1981.

———. Christmas in Georgia . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964.

———. Day by Day with Celestine Sibley. New York: Doubleday, 1975.

———. Dear Store: An Affectionate Portrait of Rich's. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967.

———. Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle: A Kate Mulcay Mystery. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

———. Especially at Christmas. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969.

———. For All Seasons. Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Publishers, 1984.

———. "Forward." Atlanta: A Brave and Beautiful City, by Peter Beney. Atlanta: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd., 1986.

———. Jincey New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978.

———. Mothers Are Always Special. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970.

———. Peachtree Street U.S.A. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963.

———. The Sweet Apple Gardening Book. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972.

———. Small Blessings . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977.

———. Spider in the Sink. New York: Harper Collins, 1997.

———. Straight as an Arrow: A Kate Mulcay Mystery. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

———. The Malignant Heart. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1958.

———. Tokens of Myself. Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1990.

———. Turned Funny. New York: HarperCollins, 1988.

———.Young'uns: A Celebration. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

Stone, Clarence. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946-1988. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1989.

Links

Kundell, James E. and Margaret Myszewski. "Urban Sprawl," New Georgia Encyclopedia.

http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-763

Purcell, Kim. "Celestine Sibley (1914-1999)," New Georgia Encyclopedia.

http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1250

Similar Publications

| 1. | Raymond Williams and Leo Marx discuss this type of pastoral in their respective works, The Country and The City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973) and The Machine in the Garden (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ashmead was an editor at Doubleday, then at Simon & Schuster, and finally, at Harper & Row; Sibley followed him to each publishing house. Sibley's published works include: the semi-autobiographical novelsJincey (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978) and Children, My Children (New York: Harper & Row, 1981);Young'uns: A Celebration (New York: Harper & Row, 1982); her memoir, Turned Funny; six mysteries, The Malignant Heart (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1958), Ah, Sweet Mystery: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), Straight as an Arrow: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), A Plague of Kinfolks: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), and Spider in the Sink: A Kate Mulcay Mystery (New York: HarperCollins, 1997); two works on Atlanta, Peachtree Street U.S.A. (1963), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1986, and Dear Store: An Affectionate Portrait of Rich's (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1990; two books on her cabin in North Georgia, including A Place Called Sweet Apple: Country Living and Southern Recipes (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, and The Sweet Apple Gardening Book (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972); collections of her columns, including Christmas in Georgia (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Especially at Christmas (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Mothers Are Always Special (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), reissued by Peachtree Publishers in 1985, Day by Day with Celestine Sibley (New York: Doubleday, 1975), Small Blessings (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977), For All Seasons (Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Publishers, 1984); and Tokens of Myself (Atlanta, GA: Longstreet Press, 1990). She also wrote the foreword to Peter Beney's collection of photographs titled Atlanta: A Brave and Beautiful City (Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd., 1986) and the text for The Magical Realm of Sallie Middleton (Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House, 1980). Note: I use parenthetical citations for page numbers from these novels and the following abbreviations for each book: ASM for Ah, Sweet Mystery; PK for A Plague of Kinfolks; SS for Spider in the Sink; and DH for Dire Happenings at Scratch Ankle. |

| 3. | "Atlanta Metropolitan Growth Since 1960," http://demographia.com/db-atl1960.htm (accessed January 10, 2009). |

| 4. | My thanks to an anonymous Southern Spaces editorial reviewer for pointing me to these demographic trends and their connection to Sibley's move from midtown Atlanta to north Fulton County. See generally Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007) and Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005). |

| 5. | Williams, 1. |

| 6. | Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 121. |

| 7. | Ibid., 5. Italics in original. |

| 8. | Ibid., 151. |

| 9. | Stephanie Foote, Regional Fictions: Culture and Identity in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 3-6, 13-14. |

| 10. | For a rich discussion of the development and growth of these neighborhoods on the western, southwestern, and southern edges of the city of Atlanta from World War II forward, see Andrew Wiese's talk, "African American Suburban Development in Atlanta," Southern Spaces, http://www.southernspaces.org/2006/african-american-suburban-development-atlanta (accessed January 10, 2009). |

| 11. | One exception to this is Sibley's chapter on African Americans in a chapter from Peachtree Street U.S.A., entitled "The Darker Third." |

| 12. | Massey, 165-66. Massey argues that the effects of globalization in the later part of the twentieth century "have undermined an older sense of a 'place-called-home,' and left us placeless and disorientated" (163), which helps to explain people's searches for rooted-ness. |

| 13. | Sibley, A Place Called Sweet Apple, 57-58; Sibley, Tokens of Myself, 15. (This column originally appeared on October 11, 1983.) |

| 14. | Sibley claims that his boss at the AP shattered his confidence in the early 1940s, and an offer was made to Celestine to switch jobs with her husband. She declined, and Little was fired. He took a job at theJacksonville Journal while Sibley stayed in Atlanta with the kids. When Sibley considered quitting theConstitution to join him in Florida, Ralph McGill offered to hire Jim. In August 1943, Sibley gave birth to their third child, Mary. Little was fired from the paper before Celestine's pregnancy was known, and he went to work at the Bell Aircraft bomber plant editing their publications. He continued to drink heavily, and he began to have an affair with a woman he met at the plant, calling it off only after Sibley confronted him. Sibley, Turned Funny, 119-23. |

| 15. | Sibley, Turned Funny, 147-48. The play Turned Funny, adapted from Sibley's memoir, implies that Ralph McGill offered her a column as a way to prevent her from having to contribute to confessional magazines for extra money. Phillip DePoy wrote the play, which had its debut under the direction of Fred Chappell at the Theatre in the Square in Marietta, Georgia, August 6-September 24, 2006. |

| 16. | Turned Funny, 166-67. The Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution came under common ownership in June 1950, when James M. Cox purchased the Constitution. "The Constitution continued as a morning paper with a liberal editorial bent, while the afternoon Journal had a more conservative leaning," states the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The two papers combined newsroom staffs in 1982, but did not officially merge into theJournal-Constitution until 2001. The New Georgia Encyclopedia, s.v. "Atlanta Journal-Constitution," http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.com/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-1807&sug=y (accessed September 29, 2006). |

| 17. | Turned Funny, 177-78. |

| 18. | Mary seems to have been a somewhat unpredictable young woman. In 1965, for example, she ran away to Montgomery, Alabama, to join in the March to Selma. Upon learning of Mary's flight, Sibley called Martin Luther King and asked him the personal favor of having one of his lieutenants escort her back to Atlanta, which he did. Sibley wrote in 1968 that upon hearing of his assassination, she realized she had never thanked him. Celestine Sibley, "In the Rain by a Mississippi Truck Stop," Atlanta Constitution, April 9, 1968. Letters between Sibley and her New York editor, Larry Ashmead, also indicate that Mary had forged checks on her mother's account in the 1970s. |

| 19. | Celestine Sibley Fleming and Sibley Fleming. Celestine Sibley: A Granddaughter's Reminiscence(Athens, Georgia: Hill Street Press, 2000), 28-29. |

| 20. | Sibley, Turned Funny, 258. |

| 21. | Celestine was convinced that the children had been brainwashed, and she believed that Mary was an innocent victim of Cricket's irrational behavior. Sibley Fleming provides a somewhat different account of that period of her childhood. Fleming claims that her mother drank excessively (which Celestine also alludes to in the fictional character of Leslie in Children, My Children) and that she threatened suicide in front of Fleming and her brother. She was at times abusive, especially when she thought that Cricket was having an affair. After moving to New Harmony, Indiana, to live with their paternal grandparents, they told their father that they wanted to talk to Celestine. He would allow it, but he said that they had to tell Sibley what Mary was like as a mother. When they did, claims Fleming, Celestine refused to believe them. But Sibley had always been the one who came to their rescue. For example, when Fleming's Uncle Jimmy, Celestine's first born, allegedly molested her one night when Celestine was out of town, Celestine immediately sent money to pay for a bus ticket to get Jimmy out of their house. Despite the protection Celestine Sibley had always given her grandchildren, she failed to believe their assessment of their mother—her daughter—as unfit, which in turn pushed those children further away. Fleming, Celestine, 55-65. Two letters to Celestine Sibley from her editor, Larry Ashmead, suggest that she had told him about her concern over Jimmy. Ashmead wrote in July 1975 that Jimmy is "so nice and so bright and my heart hurts for his lack of motivation and utilization"; a month later, he cryptically wrote to Sibley that "it is best for Jimmy" but that he understood "it" had caused her to feel low. Larry Ashmead to Celestine Sibley, July 16, 1975 and August 8, 1975, Box 2, Folder 8, Celestine Sibley Papers, MARBL, Woodruff Library, Emory University. |