Overview

In 2007, Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL) acquired the records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) documenting the activities of the organization from 1968–2007. This collection of materials relating to the struggle for social justice is now open to researchers.

The SCLC Collection

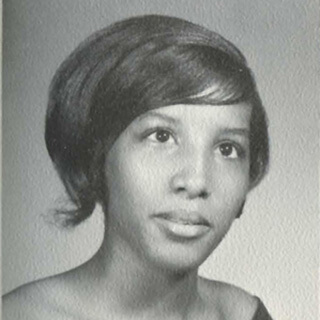

|

| Elaine Tomlin, Joseph Lowery leading a prayer during the 1982 Pilgrimage to Washington for Voting Rights, Peace, Economic Justice, North Carolina, 1982. Courtesy of SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

Founded in 1957 by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and other civil rights leaders, including Ralph David Abernathy, Ella Baker, Joseph E. Lowery, Bayard Rustin, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Charles Kenzie (C.K.) Steele, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference grew out of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Its initial intention was to secure the desegregation of transportation systems throughout the South. However, the SCLC quickly expanded the scope of its mission to ending all forms of segregation through nonviolent direct action. The organization was central to much of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, including voter registration drives in Mississippi and Alabama, the March on Washington, and establishing citizenship schools in the South.1David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986), 83–125.

Well-documented with regard to King's leadership, the story of SCLC in the years after 1968, and its continuing pursuit of nonviolent direct action as a remedy for social injustice, remains largely unexamined.2For organizational histories of SCLC post-1968, see F. Carl Walton, "The Southern Christian Leadership Conference: Beyond the Civil Rights movement," in Black Civil Rights Organizations in the Post-Civil Rights Era, ed. Ollie A. Johnson, III and Karin L. Stanford (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 132–149; and Thomas R. Peake, Keeping the Dream Alive: A History of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference from King to the Nineteen-Eighties, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1987). The long inaccessibility of SCLC's records from this period has now ended, and, after three years of processing made possible by a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources, the organization’s archive is available at MARBL.3This article makes use of some material originally published in the Robert W. Woodruff Library Blog.[http://web.library.emory.edu/blog/tag/tags/southern-christian-leadership-conference-records]

Comprising 918 boxes of administrative documents, photographs, printed and audiovisual material documenting the SCLC, the collection includes records dating to the founding of the organization in 1957. The vast majority of material covers 1968–2007.4Records from the first ten years of the organization can be found either at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change or as part of the Morehouse King Collection at the Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center. The SCLC records at MARBL primarily document the presidencies of Ralph David Abernathy (1968–1977) and Joseph E. Lowery (1977–1997). The collection holds some material from the presidency of Martin Luther King, III (1997–2003). The records starkly display the differences in leadership styles, particularly between Abernathy and Lowery. Researchers can also chart the SCLC's activities through the 2000s.

The SCLC collection enables a deeper understanding of the ongoing struggle for social justice and provides new knowledge of the many women and men whose daily work advanced the movement. These records document the activities of numerous staff members throughout SCLC history.

Figures in the SCLC

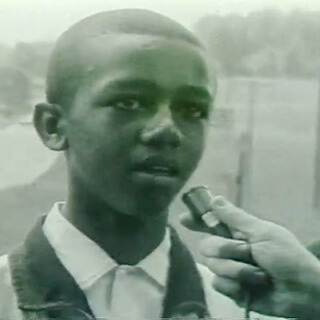

|

| Elaine Tomlin, Fred Taylor at his desk at SCLC, circa 1970s. Courtesy of SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

Among the SCLC staffers represented in the collection is Fred Taylor, who worked for the organization for nearly forty years with significant responsibility for daily management. Born in Prattville, Alabama, in 1942, Taylor was raised by his grandparents who moved to Montgomery in 1953. He became involved in the Civil Rights Movement at age thirteen, handing out leaflets during the Montgomery Bus Boycott under the direction of his pastor, Ralph David Abernathy. Taylor graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Montgomery and went on to Alabama State University, finishing his BA degree in 1965. In 1969, Taylor graduated from the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, Georgia, with a Master of Divinity degree and began working for SCLC under Abernathy’s direction. Taylor worked his way from research assistant to the directorship of the department of chapters and affiliates.

By 1984, Taylor was responsible for coordinating efforts such as the 1988 Martin Luther King Pilgrimage for Economic Justice and the 1985 boycott of Winn-Dixie supermarkets, as well as intervening on behalf of citizens’ experiencing racial discrimination and hardships. He helped plan many direct actions, including the southern leg of the 1976 Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice.

The SCLC records document that between 1969 and his retirement in the mid-2000s, Taylor was involved in every major action launched by the organization. He was a board member of the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice throughout the 1980s and 1990s (working closely with Anne Braden and Ben Chavis) and a vocal member of the anti-death penalty movement. Taylor maintained an active speaking and ministerial schedule outside of the SCLC.5Fred Taylor resumes, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University.

The SCLC records also reveal the problematic relationships SCLC had with women in the Movement. Although Ella Baker was a founding member, the first staff person hired by SCLC, and interim executive director for two years, her relationship with King and other men in the organization was notably fraught.6Garrow, 141. See the discussion of SCLC leadership in Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). For years, the women of SCLC were relegated to stereotypically “female” positions within the organization, serving mainly as secretaries and assistants. Those who headed departments found themselves in charge of education and student and youth outreach. Despite the enormous contributions women such as Septima Clark, Dorothy Cotton, and others made to the organization and the Civil Rights Movement, they filled traditionally defined female roles.

SCLC’s relationship with women outside the organization was equally complicated, and the collection captures this as well. From 1967–1979, SCLC produced a half-hour radio series, Martin Luther King Speaks. Bookended by excerpts from Dr. King, the program featured speeches by men such as Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young. Martin Luther King Speaks addressed such controversies as the student movement, poverty, Black Power, and the Vietnam War. The radio series included women activists such as Angela Davis, Dorothy Height and Eleanor Holmes Norton. Following the publication of their controversial book Abortion Rap (1971), both Florynce Kennedy and Diane Schulder appeared on the radio series to discuss the book and the court case that spawned it, as well as reproductive rights, sex, and the roles of the church, media and government in the oppression of women.7Program 7126, “Abortion Rap,” “discussion with Florynce Kennedy and Diane Schulder,” June 27, 1971, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. The SCLC collection contains audio recordings of these radio programs, transcripts of aired interviews, and unedited production transcripts.

Feminists often expressed reservations and concerns about the position of women within SCLC. In the unedited transcript of an interview recorded in Boston on November 1, 1970, lawyer and activist Pauli Murray expressed her ambivalence toward the organization:

While I am recording this material on behalf of SCLC, . . . for quite some time, I’ve had grave reservations about the policies of . . . SCLC which date back to my observations of . . . the late Dr. Martin Luther King. . . . [I]t was my impression from observing him, things that I heard and also from his general . . . policy with respect to his organization that Dr. King either had a . . . blind spot where women were concerned or did not feel . . . they were important enough to . . . make them significant . . . and equal parts of his organization and it seems to me that that same policy is being carried out . . . with the present structure of SCLC. . . . I cannot help but think that an organization which ignores half of its . . . potential membership or half of the population today in its particular struggle . . . is doomed.8Pauli Murray interview, Boston, Massachusetts, November 1, 1970, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University.

Murray drew parallels between current struggles of women to achieve equal rights with the ongoing struggle of African Americans:

I will go further and say that it may well be that we will not be able to eliminate race discrimination until we have eliminated sex discrimination because of the fact that in the subordinate position of women, we cut across all racial, class, social, economic lines and . . . so vast a segment of the population is involved that even with the best of intentions to try to resolve the racial question . . . you will never know whether you have solved it as long as half of its . . . membership, half of the non-white population, is left in this subordinate position.9Ibid.

SCLC After Martin Luther King, Jr.

The real strength of the collection housed at MARBL lies in its documentation of the SCLC since 1968. The organization floundered in the years immediately following King’s assassination. Financial difficulties abounded. Abernathy's first project as president was the Poor People's Campaign in Washington, DC, intended to dramatize and highlight the ongoing problem of US poverty. In May 1968, demonstrators traveled by mule train from around the country to the National Mall where they constructed a settlement, Resurrection City, and demanded better access to jobs, jobs training, housing, and food stamps. Intended to embody SCLC’s vision for the nation, Resurrection City was also meant to be a stark example of the plight of the poor.

|

| Selected page from Ralph David Abernathy's Letter from a Charleston Jail, April 1969. Courtesy of SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

Resurrection City leaders met with staff at the departments of agriculture and labor while protestors demonstrated outside. Plagued with a variety of problems, the settlement ultimately melted under heavy rains and mud. Its culminating moment was a Solidarity Day rally on June 19, featuring a march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial and speeches from civil rights leaders and politicians. Continued demonstrations at the Department of Agriculture on June 23 erupted in violence, which spread to Resurrection City and ended with police throwing tear gas into the camp. On the morning of June 24, as police evicted the remaining citizens and began to dismantle the plywood town, Abernathy and many others were arrested during a sit-in in front of the Capitol.

Although Resurrection City had ended, the Poor People’s Campaign would be resurrected for several months in 1969 as part of an ongoing emphasis on economic justice and the rights of workers.10Abernathy, 499–539; Peake, 237–242. The SCLC collection contains materials relating to the efforts of Charleston, South Carolina, hospital workers to unionize. Abernathy, along with other civil rights leaders, conducted nonviolence training workshops for demonstrators, spoke in churches and led rallies to protest the firing of pro-union workers. He was arrested twice and spent several weeks in jail.

Abernathy saw the action in Charleston as a test of his leadership abilities:

The Poor People’s Campaign had been conceived and planned under Martin’s leadership, and whatever positive gains we made were attributed to him, while the failures were attributed to me. But the Charleston campaign had been planned and executed under my leadership, and some of the remaining doubters had been silenced. For the first time people were beginning to believe that the SCLC would have a life and a purpose beyond completing the projects already begun by Martin.11Abernathy, 575.

Abernathy continued to focus the organization’s efforts on the plight of the poor throughout the 1970s. He also spoke out against the war in Vietnam and kept up a rigorous schedule of promoting SCLC’s work and garnering new supporters. Financial problems and internal tensions ultimately led Abernathy to resign.12Ibid., 579–586. He was succeeded by Joseph E. Lowery.

The SCLC papers document a renewed vigor in the organization under Lowery’s tenure, as well as a greater willingness to court controversy in the interest of furthering the organization’s goals. In 1979, Lowery and a delegation of Civil Rights leaders traveled to Lebanon to meet with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and present a cease-fire proposal. The delegation met with President Elias Sarkas and PLO chief Yasser Arafat, as well as private citizens. The move was unpopular, and SCLC received much criticism from figures such as Bayard Rustin and Vernon Jordan. SCLC also received a significant amount of correspondence, some in support of the trip and some from former SCLC supporters vowing never to contribute to the organization again. Lowery defended the trip as he sought to position SCLC as a voice of Christian conscience in foreign affairs.13Peake, 371–373; Correspondence, September–October 1979, President Joseph E. Lowery files, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Lowery kept SCLC involved in controversies ranging from ending apartheid in South Africa to the conflict between the Sandinistas and the Nicaraguan government.14President Joseph E. Lowery files, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University.

In September 1985, SCLC launched a successful boycott of Winn-Dixie Grocery Stores for selling products grown or manufactured in South Africa. Lowery and SCLC equated the practice of apartheid in South Africa to the practice of racism in the southern United States. In a letter to SCLC’s membership, Lowery described Winn-Dixie’s business in South Africa as an insult to the grocery chain’s African American customer base and condemned what he saw as endemic racism in the company.15Letter to SCLC members from Joseph E. Lowery, October 22, 1985, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University.

|

| Draft of Wings of Hope Implementation Manual, circa 1995. Courtesy of SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

The SCLC papers show that the organization received broad support for the boycott from citizens and legislators. Andrew Young and Walter Fauntroy joined the picket line. Georgia Representative Bob Holmes, along with seven other state representatives, applauded SCLC’s efforts and not only called for Winn-Dixie to pull South African products from their shelves but also encouraged them to hire more African Americans.16“Legislators Join SCLC Boycott of Winn-Dixie,” The Atlanta Voice, October 26–November 1, 1985, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. The boycott resulted in meetings with Winn-Dixie leadership and ultimately led the company to cease business with South Africa and pull the country’s products from grocery store shelves.17Winn-Dixie boycott, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University.

SCLC also addressed urban violence, access to health care among minority populations, and drug abuse. The Stop the Killing, End the Violence initiative of the 1990s involved a gun buyback component in which SCLC partnered with other organizations to purchase guns from residents of crime-ridden neighborhoods.18Stop the Killing, End the Violence records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. The Wings of Hope Anti-Drug Program focused on training clergy and the Black church to combat drug abuse and addiction.19Wings of Hope Anti-Drug Program records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University.

In 1984, SCLC spearheaded a series of hearings called the Crisis in Health Care for Black and Poor Americans, a result of Reagan-era budget cuts that targeted services in poor and minority neighborhoods. Hearings were held in eleven cities, and testimony collected from citizens, medical professionals, and lawmakers detailing the difficulties of minorities in obtaining adequate health care.20Crisis in Health Care for Black and Poor Americans records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. SCLC argued that traditional principles and tactics of nonviolent direct action could be successfully brought to bear under any number of circumstances adversely affecting the quality of life of minorities in America.

A rich historical resource for the movement for social justice between the late 1960s and the early twenty-first century, the SCLC collection opened to researchers on May 1, 2012 at Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library.

Recommended Resources

Abernathy, Ralph David. And the Walls Came Tumbling Down. New York: Harper & Row, 1989.

Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986.

Peake, Thomas R. Keeping the Dream Alive: A History of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference from King to the Nineteen-Eighties. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1987.

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records. Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Walton, F. Carl. "The Southern Christian Leadership Conference: Beyond the Civil Rights movement." In Black Civil Rights Organizations in the Post-Civil Rights Era, ed. Ollie A. Johnson, III and Karin L. Stanford, 132–149. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Links

Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

http://marbl.library.emory.edu/.

Emory Finding Aids: Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, 1864–2007

Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/90wfs.

SCLC Entries in the Robert W. Woodruff Library Blog

http://web.library.emory.edu/blog/tag/tags/southern-christian-leadership-conference-records.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

http://sclcnational.org/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1986), 83–125. |

|---|---|

| 2. | For organizational histories of SCLC post-1968, see F. Carl Walton, "The Southern Christian Leadership Conference: Beyond the Civil Rights movement," in Black Civil Rights Organizations in the Post-Civil Rights Era, ed. Ollie A. Johnson, III and Karin L. Stanford (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 132–149; and Thomas R. Peake, Keeping the Dream Alive: A History of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference from King to the Nineteen-Eighties, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1987). |

| 3. | This article makes use of some material originally published in the Robert W. Woodruff Library Blog.[http://web.library.emory.edu/blog/tag/tags/southern-christian-leadership-conference-records] |

| 4. | Records from the first ten years of the organization can be found either at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change or as part of the Morehouse King Collection at the Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center. |

| 5. | Fred Taylor resumes, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University. |

| 6. | Garrow, 141. See the discussion of SCLC leadership in Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). |

| 7. | Program 7126, “Abortion Rap,” “discussion with Florynce Kennedy and Diane Schulder,” June 27, 1971, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 8. | Pauli Murray interview, Boston, Massachusetts, November 1, 1970, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 9. | Ibid. |

| 10. | Abernathy, 499–539; Peake, 237–242. |

| 11. | Abernathy, 575. |

| 12. | Ibid., 579–586. |

| 13. | Peake, 371–373; Correspondence, September–October 1979, President Joseph E. Lowery files, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 14. | President Joseph E. Lowery files, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 15. | Letter to SCLC members from Joseph E. Lowery, October 22, 1985, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 16. | “Legislators Join SCLC Boycott of Winn-Dixie,” The Atlanta Voice, October 26–November 1, 1985, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 17. | Winn-Dixie boycott, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 18. | Stop the Killing, End the Violence records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 19. | Wings of Hope Anti-Drug Program records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |

| 20. | Crisis in Health Care for Black and Poor Americans records, SCLC records, MARBL, Emory University. |