Overview

Holly Markovitz Goldstein examines what happens when an iconic site of oppression and injustice becomes a tourist destination. Placing special emphasis on visual culture in the forms of photographs and postcards, Goldstein unpacks the complicated history of St. Augustine's "Slave Market."

"St. Augustine's 'Slave Market': A Visual History" was selected for the 2011 Southern Spaces series "Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary publications about natural and built environments.

Introduction

|  |  |

| Figures 1–3. Holly Goldstein, Public Market in the Plaza de la Constitución, three views, St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. Figure 1. View from behind and left. Figure 2. View from front. Figure 3. View from behind and right. | ||

At the center of the historic quarter in St. Augustine, Florida, stands the "old slave market," an open-air pavilion where enslaved Africans were bought and sold (Figures 1–3). Since its construction in the early nineteenth century, the waterfront structure has transformed from marketplace to leisure plaza to a locus for civic festivals and political protests. Largely ignored by locals and overlooked by tourists, the market sits empty in the center of America’s oldest continuously inhabited, European-established city. Despite its changing purposes, it remains best known by the vernacular name "slave market," a tangible reminder of slavery. Although the structure was initially built to house the exchange of foods and commercial goods, newspaper reports and city records document slave sales here. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, entrepreneurs depicted the pavilion as a "slave market" in postcards, photographs, and guidebooks to entice tourists. Denials by local whites flew thickly. In a 1914 letter to The St. Augustine Record, J. Gardner writes,

I have seen the legend of the old slave market. I want to state that this is a fabrication, to pander to the morbid tastes of a certain class that come or came down to our section with the hope and desire to see only the revolting and objectional side of the picture. This market when I knew it stood near the plaza, if my memory serves me, and only fish meats and vegetables were sold there.1J. Gardner, letter to the editor, St. Augustine Record, July 14, 1914. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library.

Accurate and sensationalist, the designation "slave market" stuck to this contested site.

The earliest photographs of the market, made in the 1860s and 1870s, depict the pavilion as a destination for incoming ships' cargo and a pleasant place to gather. In the 1880s and 1890s, when new hotels and a railroad developed by Henry Flagler incited a tourist boom, enterprising photographers sold images of a "slave market" that attracted northerners eager to glimpse something of the antebellum South's oppressive past. Depicted on postcards and illustrated in post-bellum guidebooks as a must-see tourist attraction, the "slave market" was a chilling and nostalgic relic. Through the first half of the twentieth century, as St. Augustine became a fashionable winter resort and a bustling tourist destination, the market retained its association with slavery. In the 1960s, commemorating those who were traded on its steps, civil rights protestors including Martin Luther King, Jr., and Andrew Young led nightly marches around the market, enduring physical violence and arrest. The "slave market" became the focal point for the 1964 St. Augustine Movement—a clash between nonviolent protestors and segregationists—prior to President Lyndon Johnson's signing the Civil Rights Act.2Dan R. Warren, If it Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine 1964 (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2008). In 2011 St. Augustine installed its first public civil rights monument adjacent to the market, honoring the struggle for equality on this site of white terror.

St. Augustine's Plaza de la Constitución, the town square on which the market sits, hosts monuments for each stage in the city's history, from an 1813 colonial Spanish obelisk, to Civil War cannons, to the 2011 St. Augustine Civil Rights Foot Soldiers Monument. Loaded with meaning, the architecture of the "slave market" represents hurt and healing, repression and reparation.

St. Augustine, the "Slave Market," and the Plaza de la Constitución

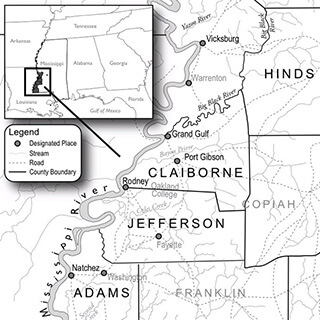

Seeking the fountain of youth, the Spaniard Juan Ponce de León explored the St. Augustine area in 1513. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded the colonial city after sighting land on August 28, 1565 (the feast day of Saint Augustine of Hippo). Spanish rule lasted for two hundred years, ending in 1763 when the Treaty of Paris ceded St. Augustine to England. Spanish rule returned in 1784. After the 1821 Adams–Onís Treaty created the Florida Territory, St. Augustine became an American possession.3Michael Gannon, ed., The New History of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996).

Fortified on Matanzas Bay by the stalwart Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine withstood centuries of conflict between Spanish, British, and French troops, and harbors a history of invasion. Sixteenth-century colonists displaced the indigenous Timucua population, and the Second Seminole War erupted in 1835.4Jerald Milanich, Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995). Spanish settlers in St. Augustine owned some of America's first slaves.5Jane Landers, "Spanish Sanctuary: Fugitives in Florida, 1687–1790," Florida Historical Quarterly 62, no. 3 (1984); Jane Landers, ed., Against the Odds: Free Blacks in the Slave Societies of the America (London: Frank Cass, 1996); and Margo Pope, "Slavery and the Oldest City," The St. Augustine Record, December 2, 2001. Fort Mose, founded in 1738, was the first legally recognized free community of ex-slaves in what was to become the United States.6See Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995); and Jane Landers, "Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose: A Free Black Town in Spanish Colonial Florida," American Historical Review 95, no. 1 (Fall 1990). While traces of these cultures remain in St. Augustine—British flags fly, an excavated Timucua village is a "Fountain of Youth" sightseeing attraction—the history on display largely evokes Spanish colonial style.7For histories of black and indigenous cultures in the southeastern coast region, see Jane Landers, ed., The African American Heritage of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995); and Kathleen A. Deagan, "Mestizaje in Colonial St. Augustine," Ethnohistory 20, no. 1 (Winter 1973): 55–65. Colonial and modern buildings line narrow streets. The historic district features T-shirt shops and ice cream parlors. Sightseers ride trolleys, visit wax museums and the original Ripley's Believe It or Not, patronize "authentically old" and recently constructed sites. The Excelsior Museum and Cultural Center located in historically black Lincolnville (established by former slaves in 1866), and the self-guided ACCORD Freedom Trail educate visitors about the city's role in the civil rights movement.8David Nolan, "Lincolnville, once called 'Africa,' Developed Following Emancipation," The St. Augustine Record, February 23, 2004.

|

| Figure 4. Public Market in the Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, 1893. Appearance of rebuilt market after 1887 fire. Photonegative of a cyanotype. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida. |

St. Augustine has always had a public market. When the sixteenth-century Spanish founded the city, meat and vegetable stalls occupied the waterfront site where today Cathedral Place and King Street intersect with Highway A1A. A central public plaza was part of the colonial city plan, in accordance with King Phillip II's Spanish Royal Ordinance of 1573 mandating an official plan for all colonial towns.9According to the Royal Ordinance, the plaza, surrounded by the most important governmental and ecclesiastical buildings, was to function as the principal recreational and meeting area. In 1598 Governor Gonzalo Mendez de Canzo wrote to the Spanish crown, "After my arrival I caused a market place to be established, where there would be weight and measure, which heretofore had been lacking." From the Florida Master Site File for the public market, found in the Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board Historic Properties Inventory Form. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. Commercial, ecclesiastical, and government institutions bordered the Plaza de la Constitución. A fence formerly divided the "plaza" from the "market" to separate the sale of meat and produce—where horse-carts could unload goods—from the town's assembly site, government house, and gardens. The British erected a marketplace (with a bell and beam scales) that occasionally served as a guardhouse.10J. Carver Harris, ed., "The Public Market Place," El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 54 (October 1964): 1–18. The Spanish previously used the market as a guardhouse. A masonry structure with four bays under heavy piers and a pitched roof, built by city leaders in 1824, provided the first permanent sanitary space for selling food. The city constructed the current six-bayed structure in 1888, one year after a devastating fire (Figure 4).

The waters of Matanzas Bay originally reached almost to the market's steps (the boat basin was filled in 1900), making it an easy shipping destination (Figure 5).11In 1840 a commercial boat basin was created in Matanzas Bay to provide easier ship access to St. Augustine's port. The basin was filled in 1900 and a bridge has spanned the waterway between St. Augustine and Anastasia since 1985. The Bridge of Lions, still standing today, dates to 1927. Two photographs depict the 1824 market and plaza before the 1887 fire. The first known photograph of the market, made with a long exposure by Civil War photographer Samuel Cooley in winter 1864, presents the relatively unpopulated port's commercial waterfront (Figure 6). Developing glass negatives in a traveling darkroom, Cooley created a photographic survey of cities and forts for the US Army's Department of the South.12Photographers Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. Atop the public market (at right) is a cupola with a bell to announce market days. A weathervane erected a few years later would boast the image of a bull, signaling the meat sold there. Directly to the left of the pavilion at the water's edge is the wooden fish market standing on stilts. Further left, government and commercial structures border the plaza. In the distance, Trinity Church's spire marks the beginning of St. Augustine's skyline. An 1884 photograph depicts a boat with a load of oranges ready for sale (Figure 7). A stereocard from the late 1800s depicts food carts next to the pavilion, empty after a day of selling (Figure 8). While many images of the market show no people, an 1895 photograph of horse carts on the road and patrons inside the market reveals a bustling scene (Figure 9). The city's meat and produce market eventually moved indoors, and the era of daily food for sale in the waterfront pavilion came to an end.13Harris, ed., "The Public Market Place."

The public market anchors the east end of St. Augustine's Plaza de la Constitución (Figures 10–12). The term "slave market" did not enter popular use until the 1870s, and the market is just one among many monuments competing for visitors' attention. The plaza's oldest structure, an 1813 coquina monument, commemorates the 1812 Constitution of Spain (Figure 13).14St. Augustine's obelisk may be the only monument dedicated to the Spanish Constitution in the Western Hemisphere. "Art Images of Monument to the Spanish Constitution of 1812," The St. Augustine Record, September 8, 2011. Public works from St. Augustine's colonial history include a reconstructed seventeenth-century well in the plaza's center and remains of an eighteenth-century Spanish well on its western border (Figures 14–15). No monuments publicly commemorate the Native American past. The only Native presence in the plaza adorns the Florida state seal, atop historical markers erected in the 1970s (Figures 16–18).

The plaza's tallest monument was erected in 1872 by the Ladies Memorial Society for the Confederate dead, and stands adjacent to the "slave market" (Figure 19).15Founded in September 1866, the Ladies Memorial Society consisted of socially prominent white St. Augustine women, mostly wives and relatives of Confederate soldiers. Monuments for soldiers killed in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War are accompanied by Civil War cast iron guns and stacks of cannonballs (Figures 20–26). A plaque erected by Florida's Daughters of the American Revolution memorializes American prisoners of war captured by British troops and held during the American Revolution at Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) (Figure 27). A bandstand and gazebo renovated in 2011 recall Gilded Age tourists (Figure 28). At the plaza's eastern border overlooking the bay stands a statue of Juan Ponce de León, who "landed near this spot in 1513" (Figures 29–31). Bordering the plaza's perimeter, next to a wax museum, restaurants, and souvenir shops, are Trinity Church, the Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine, and the historic Government House (Figures 32–34).

|  |

| Figure 35. Holly Goldstein, St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument, Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. The Foot Soldiers Monument overlooks a former Woolworth's where desegregation sit-ins occurred in the 1960s. | Figures 36–38. Holly Goldstein, Andrew Young Crossing Monument, Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. Figure 36 shows the length of the path. Figure 37 highlights the footsteps. Figure 38 focuses on a quotation by Andrew Jackson. |

Located directly south of the "slave market," the plaza's first civil rights memorial, the 2011 St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument, overlooks a former Woolworth's where desegregation sit-ins occurred in the 1960s (Figure 35). Four sculpted heads, an unnamed African American man, woman, and teenage girl, and a white male college student, represent the protesters who fought for an end to segregation in St. Augustine. The plaque reads,

Dedicated to those who participated in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s in St. Augustine. They protested racial discrimination by marching, picketing, kneeling-in at churches, sitting-in at lunch counters, wading-in at beaches, attending rallies, raising money, preparing meals and providing safe haven. They persisted in the face of jailings, beatings, shootings, loss of employment, threats, and other dangers. They were Foot Soldiers for Freedom and Justice whose efforts and example helped to pass the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. Their courage and heroism changed America and inspired the world.

A bas-relief sculpture behind the four heads presents the plaza as a backdrop for the fight for racial equality. Commissioned by the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Remembrance Project (directed by Foot Soldier Barbara Vickers) the $70,000 project came to fruition after seven years of planning and a 2009 amendment to a City Code that barred new monuments in the plaza celebrating historical events occurring after 1821.16David Nolan, interview with the author, March 22, 2012; City Commission Meeting notes: "City of St. Augustine, Regular City Commission Meeting, April 27, 2009," accessed April 1, 2012, http://www.staugustinegovernment.com/your_government/documents/CCMinutes04.27.09.pdf. The racial population of St. Augustine has changed since the 1960s, with an influx of white notherners in the 1970s–1990s. Whereas the black population hovered around twenty-five percent in the 1960s, today it is below ten percent. Zach Gray, "Racism in St. Augustine, Not Just a Thing of the Past," Flagler College Gargoyle, April 26, 2012. St. Augustine Mayor Joseph Boles, Jr. noted in his dedication speech that visitors would "see this monument next to the Old Slave Market where evil held forth in the diatribes and hate speech of the KKK during the marches and they will know that this blessed event is designed to exorcise that nightmare."17Joseph Boles, Jr. (speech, Foot Soldiers Monument dedication ceremony, St. Augustine, FL, May 14, 2011). Although the city council initially disallowed the May 14, 2011 dedication ceremony from taking place inside the "slave market," a rainstorm relocated the gathering under the market's roof.

Two months later the city dedicated designer Jeremy Marquis's "Andrew Young Crossing," a monument to the well-known activist who led protests at the "slave market" for its symbolism of racial oppression and who was beaten here by segregationists (Figures 36–38).18Young and other demonstrators referred to the public market as the "slave market." As he writes in his memoir, "The destination of the marches in St. Augustine was the old slave market, which was unfortunately drawing large crowds of unruly whites who gathered each night to harass, threaten, and sometimes strike out at marchers." Andrew Young, An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America (New York: Harper Collins, 1998), 291. This memorial features bronze replicas of Young's footsteps alongside quotes by him, President Lyndon Johnson, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

What to Call It?

|

| Figure 39. Holly Goldstein, Plaque on northeast pillar of Public Market, Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. Figure 40. Detail. |

The St. Augustine pavilion has served as an "all-purpose protest site" from early twentieth-century socialists to suffragettes to Iraq war protesters.19David Nolan, interview with the author, March 22, 2012. "Slave market" is not found in written records until the 1870s.20For examples of the term "slave market" used prior to the 1880s, see Earnest A. Meyer, "Childhood Memories" reprinted in El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 44 (2007): 204, in which Meyer depicts the "slave market" dated 1875. An illustration in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper from May 1878 also depicts the "slave market." A portrait bust of female slave Nora August, inscribed in part, "purchased from the Market, St. Augustine, Florida April 17th 1860" is found in the sculpture collection at the Museum of the Confederacy, see Museum of the Confederacy, Before Freedom Came: African American Life in the Antebellum South (Richmond: Museum of the Confederacy and University of Virginia Press, 1991), cover, 8. As for what to call the site and how to present it publicly, plaza markers contradict each other (Figures 39–40). The predominantly white St. Augustine Historical Society now officially sanctions the structure as "a public market that had occasional slave sales." A historical marker, "Public Market Place," just south of the pavilion erected in 1970 by the St. Johns County Historical Commission details only the weights and measures first established there and omits any mention of slavery (Figures 17–18). Like much of St. Augustine's tourist infrastructure, the 1970 sign highlights Spanish colonial accounts, not African American history.

Slaves were sold in and around the public market. While most slave sales in pre-Civil War St. Augustine took place at plantations, in homes, or on boats, public transactions usually occurred on the steps of the Government House directly west of the plaza. Visiting St. Augustine in 1827, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote of the slaves he saw auctioned in the Government House yard, including the sale of "four children without the mother who had been kidnapped therefrom."21Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1909), 177, quoted in Len Gougeon, Virtue's Hero: Emerson, Antislavery, and Reform (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 33. Henry L. Richmond, "Ralph Waldo Emerson in Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly 18, no. 2 (October 1939): 75–93. Hoping that the balmy climate would cure his tuberculosis, the twenty-three-year-old Emerson saw his first slave sale while in the Government House for a Bible Society meeting. "One ear therefore heard the glad tidings of great joy," he wrote, "whilst the other was regaled with 'going gentlemen, going!'"22Gougeon, 33. Witnessing slavery firsthand confirmed his staunch abolitionism.

|  |

| Figures 17–18. Holly Goldstein, Marker for "Public Market Place," Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. Figure 17. Detail of the Marker. Figure 18. Marker for "Public Market Place" and the Market. | |

Deeds of sale and newspaper clippings document slave sales in the market. As examples, the St. John's County Deed book cites the sale of "two slaves [Malvina and Gabina, both about nineteen] . . . at public auction to the highest bidder at the market house in St. Augustine" in 1836; "the sale of a negro woman Sally at public auction in the market house" to settle the Mary Hanford estate; and the auction of twenty-eight-year-old Tamaha, for $180.23County Deed Book, 24, 126, 288. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. These slave sales and others are also documented in E. W. Lawson, "The Slave Market," Today in St. Augustine, May 21, 1939. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. The East Florida Herald advertises slave sales to be held "in the public market" from the 1820s through the 1840s.24Auction advertisement from the East Florida Herald, October 31, 1827. Also recorded in Deed Book F, 394. In addition to auctions, the market was often the site for public corporal punishment. In August 1849 "a negro man named Daniel, the property of M. Antonio Bouke, was to receive thirty-nine stripes on his back in the public market for escaping" and "a negro man named Joseph received the same punishment in the public market" one week later.25Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. The market also hosted meetings of the slave patrol, white citizens who apprehended "all slaves or free persons of color, who may be found in the streets thirty minutes after the ringing of the Bell without having a proper pass from their masters or guardians."26David Nolan, "Slaves Were Sold in Plaza Market," St. Augustine Record, September 27, 2009.

Introducing these names—Malvina, Gabina, Sally, Tamaha, Daniel, Joseph, and others—attaches human lives to St. Augustine's market, although precious few names were recorded and almost nothing is known about them. One first-person narrative, The Odyssey of an African Slave, recounts the story of Sitiki, later called Jack Smith, an African who died free in St. Augustine.27Griffin, Patricia, ed., The Odyssey of an African Slave (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009). While Sitiki was not sold at the market, his story of capture (as a five-year-old in Africa) and enslavement (traveling the eastern shore with various masters) offers a glimpse into this history.28Walter Johnson's Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001) examines the New Orleans slave market, North America's largest, where over 100,000 slaves were sold. While the rate of exchange in New Orleans vastly exceeds that of St. Augustine, Johnson's account of slave narratives, slave-owner letters, and court records offers insight into the commercial exchanges and human lives in St. Augustine.

Gilded Age Postcards and Civil Rights Photographs

|  |  |

| Figures 41–43. Holly Goldstein, The former Hotels Ponce de Leon (now Flagler College) (Figure 41), Alcazar (now City Hall and Lightner Museum) (Figure 42), and Cordoba (now Casa Monica) (Figure 43), St. Augustine, Florida, 2012. | ||

From the 1870s through the 1890s, St. Augustine transformed from a colonial town into a tourist destination for wealthy white northerners. Standard Oil tycoon Henry Flagler developed a railroad (the Florida East Coast Railway) down the Florida coast transporting tourists to his grand hotels.29Patrons of Flagler's St. Augustine's hotels were wealthy white vacationers. Thomas Graham, Flagler's St. Augustine Hotels: The Ponce de Leon, the Alcazar, and the Casa Monica (Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 2004). The Hotel Ponce de Leon, the Hotel Alcazar, and the Hotel Cordova line King Street, just steps from the Plaza de la Constitución (Figures 41–43).30The Ponce de Leon Hotel, which opened to great fanfare in 1888, is now the home of Flagler College. The Alcazar now houses City Hall and the Lightner Museum. The Cordoba still operates as a hotel, renamed the Casa Monica. These monumentally ostentatious resorts—the Alcazar housed the world's largest indoor swimming pool; the Ponce de Leon boasted Louis Comfort Tiffany windows and was one of the first American buildings to have electricity—attracted elite vacationers from northern winters. Local entrepreneurs capitalized on the wealth and curiosity of Flagler's patrons.

With its prominent location and its food-selling function central to daily life, the public market became a St. Augustine icon, appearing in paintings and photographs produced for and by tourists. An artist colony, the Ponce de Leon studios, operated adjacent to Flagler's flagship hotel. Numerous plein-air paintings depict the market as a peaceful leisure destination.31The first artist in residence at the Ponce de Leon studios was Flagler's friend Martin Johnson Heade. Artists who depicted the public market in their paintings include William Staples Drown, Robert S. German, Frank Shapleigh, and Felix de Crano. Sarah Barghini, A Society of Painters: Flagler's St. Augustine Art Colony (Palm Beach, FL: Henry Morrison Flagler Museum, 1998). To view the paintings depicting the market, see Gary Libby, ed., Reflections: Paintings of Florida 1865–1965. From the Collection of Cici and Hyatt Brown (Daytona Beach, FL: Museum of Arts and Sciences, 2009); Gary Libby, ed., Celebrating Florida: Works from the Vickers Collection (Daytona Beach, FL: Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1995); and Maybelle Mann, Art in Florida 1564–1945 (Sarasota FL: Pineapple Press, 1999).

|

| Figure 44. The Market House of St. Augustine, Florida, Formerly Used as a Slave Market, c. 1886. Stereograph from the collection: Florida: The Land of Flowers and Tropical Scenery. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida. |

Savvy photographers and postcard producers peddled images of the "slave market" to instill fascination into an ordinary-looking space. Technical advances in photomechanical reproduction and the sudden boom in tourism ushered in a golden age of picture-postcard manufacture.32Tom Phillips, The Postcard Century (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000); Marian Klamkin, Picture Postcards (New York: Dodd and Mead, 1974). Early postcard makers copied images from stereographs, such as an anonymous pre-1887 stereoview (labeled "the market house of St. Augustine, Florida, formerly used as a slave market") sold as part of the series "Florida, the Land of Flowers and Tropical Scenery" (Figure 44). More tourists and the newly available supply of postcards prompted an explosion of "slave market" cards by the 1890s and offered a picturesque attraction for sightseers.33Postcards promoting relics of slavery to tourists are not unique to St. Augustine; other slave market sites are discussed below. In addition, Jim Crow era postcards often depicted grotesque illustrations of racism and segregation such as lynching. For an extensive discussion of lynching postcards see Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). Wood notes that lynching postcards, like slave market postcards, "deemed these events both customary and spectacular." Inscribing and circulating lynching postcards "substantiate[d] white supremacist views," normalizing the inhuman practice and packaging it as entertainment. Wood, 108. The slave market postcards operate similarly, sanitizing the human slave trade into sentimental nostalgic keepsakes. George Fredrickson discusses the romantic image of blacks in The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914 (New York: Harper & Row, 1971). The images sanitize and romanticize slavery into the sentimental bygone.

Why buy a souvenir of slavery? In the years following Reconstruction, many northerners, explains historian Maurie McInnis, conceived the South as "a land of leisure and romance, a simpler place than the rapidly industrializing North. Central to that southern imaginary was a benign view of slavery, one that fantasized a harmonious relationship between masters and slaves, a natural hierarchy."34Maurie McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 220. The sanitized "slave market" postcards promoted picturesque architectural remains, not inhumanity. As the pre-1887 anonymous stereocard advertises, the empty "slave market" complemented other attractions found in Florida, the "land of flowers and tropical scenery." Viewers of antebellum relics were charmed by a "quaint antidote to the modernization and standardization" of northern cities and by the comparatively slower pace of selected southern sites.35Ibid. Architectural vestiges of slavery, such as grand plantation homes, ruins of slave quarters, and unused slave markets embodied this romanticized projection.

Historian Nina Silber argues that the northern view of the South as a "land of leisure, relaxation, and romance" stemmed from the desire for reconciliation after the Civil War.36Nina Silber, The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South: 1865–1900 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 67. "Tourism and reconciliation went hand in hand" as affluent white vacationers soaked up hospitality, food, entertainment, and accommodations.37Ibid. Flagler's indulgent hotels helped to forge a "romantic and sentimental culture of conciliation."38Ibid., 2. Plantations, slave markets, and African Americans became must-see attractions on a tour that followed the St. Johns River through Florida and invariably included a stop in St. Augustine. Picture postcards catered to these desires.

|  |

| Figure 45. W. J. Harris Co., Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Florida, 1904, recto. Collection of the Author. | Figure 46. W. J. Harris, c. 1920. Courtesy of the Harris Family. |

One popular market postcard, dated 1904, depicts the empty pavilion as a haunting reminder of slavery (Figure 45). In the image by St. Augustine photographer William James Harris (Figure 46) (1868–1940), an elderly African American man stands before the market cradling a basket in his right hand and leaning on a cane with his left.39Prior to 1912 the postcard appeared in black and white and was printed in color after 1912. Robert R. Goller, "North and South With W.J. Harris, Photographer," El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 28 (1991): 38; Robert Bogdan and Todd Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 245. Harris labeled the man an "old slave" in the caption of some versions of this postcard.40Goller, 38. The text on the front of the postcard reads, "Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Florida." The verso text reads, "The old slave market in the east end of the Plaza is an interesting landmark of antebellum days. Built in 1840." A later version was amended to include on the reverse, "It was used as a public market in which slaves were occasionally sold. Old Slave in foreground." His somber face, white beard, and rumpled clothing suggest a lifetime of hard work. He is dressed for a day in town and carries a basket perhaps for shopping; this appearance of romanticized dignity conforms to the paternalistic euphemism that old slaves were cared for or respected. As the only figure in this deserted scene, the man appears as spectral, barely suggesting the terrible history of this site. The tidy marketplace and row of shops behind it visually contrast the old man, who looks as if he hobbled into the scene. Harris's old slave is anonymous and unthreatening. He is not Malvina, Gabina, Sally, Tamaha, Daniel, or Joseph; he is defined by his approximate age, "old," and his status as property, "slave." Slavery has become a costumed actor in the St. Augustine that turn-of-the century tourists encountered. Just west, the barely visible Confederate monument peeks through trees. The storefronts at right house modern businesses.

|

| Figure 47. W. J. Harris, Public Market and "Old Slave," Plaza de la Constitución, St. Augustine, Florida, c. 1904. Copyright St. Augustine Historical Society. |

Harris's photographic negative of this scene reveals more grime and weathering on the market than is visible in the postcard (Figure 47). A comparison of postcard and photograph reveals that Harris removed foliage and pushed the trees at left into the distance to increase the market's visibility; he diminished the height of cathedral's campanile to exaggerate the pavilion's importance, removed a bicycle in the foreground, and added some summer clouds.41Research at the St. Augustine Historical Society and conversations with Harris's daughter and granddaughter did not reveal any information on the identity of the man depicted in the postcard. The market in the postcard appears modern and iconic.

W. J. Harris produced and sold this postcard in his St. Augustine studio on St. George Street and leased the image to postcard publishing houses in the United States and internationally.42Leslie Goode, personal communication with the author, March 23, 2012. See also Leslie Goode, "Harris Pictures," accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.harrispictures.com/. Harris Pictures is authored and operated by Leslie Goode, great-granddaughter of W. J. Harris. Her business currently sells t-shirts, coffee mugs, calendars, posters, and key chains emblazoned with images from Harris's postcards of St. Augustine landmarks. Although this popular image offered a clean, romantic trace of slavery and a non-threatening African American, local historians and civic boosters in a post-Reconstruction culture of forgetting sought to distance their town altogether from its slave-trading past and "set the record straight" that the structure was built to sell food, not slaves.43Nina Silber discusses how "Black people . . . assumed especially picturesque qualities" for northern tourists. Silber, 80. Susan Parker, "Was it a Public Market or a Slave Market?" The St. Augustine Record, October 28, 2007. Silber states "forgetfulness, not memory, appears to be the dominant theme of reunion culture." Silber 4. For further reading on "forgetfulness" and the historical memory of the Civil War, see David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 250–99. Blight characterizes the culture of forgetting as "reconciliationist." Responding to criticism, and after much prodding by local historians, Harris modified the postcard text to read, "The old slave market in the east end of the Plaza is an interesting landmark of antebellum days. Built in 1840 for a public market. Called "slave market" by an enterprising photographer to make his pictures sell."44Goller, 38. Of course, the "enterprising photographer" was Harris himself.45Jackie Feagin, "Slave Market Tag Came from Huckster Trying to Promote Tourism" The St. Augustine Record, Saturday July 20, 1985, 10A. The interviews conducted on March 22, 2012 by the author with the following subjects were particularly helpful: Charles Tingley, Amy Howard, David Nolan, and Howard E. Lewis. See also Goller, 38–43.

Balancing history and tourism, photographer W. J. Harris served as the business manager for the St. Augustine Historical Society, supervising some of St. Augustine's more dubious attractions, including "Luella Day McConnell's Fountain of Youth," where visitors still sip today.46Amy Howard, "Public Market (Slave Market)," published February 5, 2009, accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.augustine.com/history/black_history/slave_market/tourism.php. This article authored by historian and teacher Amy Howard details the history of the "slave market" and the chronology of slavery in St. Augustine. See also Goller 31. Harris's most vocal detractor was Charles B. Reynolds, founder of one of the nation's oldest travel agencies and author of St. Augustine's 1892 Standard Guide.47Charles Tingley, interview with the author, March 22, 2012. According to Tingley, Reynolds was the first St. Augustine historian "to take the city's attractions to task"—including the "slave market" and "oldest house"—for historical claims. The Charles Bingham Reynolds papers are in the collection of the University of Florida Smathers Libraries, Special Area Studies Collections. Reynolds (1856–1940) was originally from New York and worked for a time as editor of Forest and Stream Magazine. He helped to form the Audubon Society and partnered with Ward G. Foster to publish commercial guidebooks. Reynolds describes the Plaza de la Constitución as "A pleasing bit of greensward in the center of the town. . . . It is a public park of shrubbery and shade trees, with monuments and fountains, an antiquated marketplace inviting one to loiter, and an outlook to the east over the bay."48Charles B. Reynolds, The Standard Guide to St. Augustine (St. Augustine, FL: E. H. Reynolds, 1892), 53-4. In addition to his "Standard Guide" Reynolds published the book Old Saint Augustine: A Story of Three Centuries (St. Augustine, FL: E. H. Reynolds, 1885). Of the market, Reynolds writes,

The open structure on the east end of the Plaza is commonly pointed out as the "old slave pen" or "slave market," and it is sometimes alleged to have been of Spanish origin. It was never used as a "slave pen," nor as a "slave market," nor had the Spaniards anything to do with it, for they had left the country twenty years before it was built. . . . The market was intended for a very prosaic and commonplace use, the sale of meat and other food supplies, and it was devoted to that use. . . . It was not only until the influx of curiosity seeking tourists, after the Civil War that any one thought of dubbing the Plaza market a "slave pen" or "slave market." The ingenious photographer who labeled his views of the old meat market "slave market" sold so many of them to sensation hungry strangers that he has since retired with competence . . . [yet] the "slave market" yarns . . . have been told so often to credulous visitors that there are now some residents of St. Augustine who actually believe the stories themselves.49Reynolds, Standard Guide, 54.

Reynolds blames Harris (the "ingenious photographer") with popularizing the "yarns" which caused tourists to "stand and gape in foolish wonder at the old market; just as in like manner, perhaps, if brought into the presence of a hero of a hundred fearful conflicts, they would ignore the record of his valor and stand lost in vulgar contemplation of a wart on his nose."50Ibid. But Reynolds did not go unchallenged. Responding to an early version of Reynolds's guide, local resident S. J. Whall writes,

Dear Sir, I have many times seen slaves sold from the steps of the old market on the plaza. I have seen a ship of slaves disembarked on the beach at St Augustine, and sold at this market. My mother was the first English settler at St Augustine after the change of flags and the body of my father who died of yellow fever lies buried in the old graveyard near the city gates.51S. J. Whall, letter to Charles Reynolds, October 7, 1889. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library.

Numerous white St. Augustine residents sought to bury the "slave market" myth, including Anna M. Marcotte, editor and proprietor of The Tattler, the journal of "Society in the South." Published weekly in St. Augustine, The Tattler billed itself as "a spicy, bright paper of sixteen pages."52Reynolds, 105. Advertisement for The Tattler in Reynolds's guide. The publication was "sold on trains, in the hotels, and on news stands." Like Reynolds, Marcotte saw the "slave market" as an ugly detraction from her city's image, and her Tattler articles denounced Harris's claims.

Harris was not alone in profiting from the market's association with slavery. In a popular 1884 pamphlet, Bloomfield's Illustrated Historical Guide, Max Bloomfield writes, "East of the Confederate monument stands the old, old market. A queer-looking structure it is. . . . We have been told that before the war it had been used as a slave market. Whenever a sale was to take place the bell in the cupola would be rung to notify the public."53Max Bloomfield, Bloomfield's Illustrated Historical Guide (St. Augustine, FL: Bloomfield, 1884), 30. Bloomfield concedes later the doubtful accuracy of the slave-market-bell-ringing story, yet he delights in spreading it. Bloomfield sold his guidebook at the museum he operated near St. Augustine's city gate.

British Victorian Lady Duffus Hardy accelerated the debate over the "slave market" in her melodramatic 1883 novel Down South, written during a tour with her daughter Iza.54Born Mary Ann McDowell (1825–1891), Hardy married Sir Thomas Duffy Hardy, the Keeper of Her Majesty's Records. She published fourteen novels, some under the pseudnym Addlestone Hill. Hardy traveled to America between 1880 and 1881 with daughter Iza, also a novelist. See Helen C. Black, Notable Women Authors of the Day (London: McLaren, 1906), 198. "There is the 'Plaza de la Constitution,'" Lady Hardy writes, "where the good Christians burnt their brethren a century ago":

In the center stands the curious old market-place, roofed in at the top, but open on all sides; this was the ancient slave mart where, "God's image, carved in ebony" was bought and sold in most ungodly fashion; there is the place where they stood, like cattle in a pen, so that their purchasers might walk to and fro examining them from all points to see if they had their money's worth.55Lady Duffus Hardy, Down South (London: Chapman and Hill, 1883), 171–72.

A letter to the St. Augustine News from 1898 is typical of local complaint about the "slave market" name:

The old market house is something with an unknown history, when the lie was born . . . to call it the slave market. A breath will start slander, but the army cannot stop it. These men [postcard-makers] have acknowledged they never would have sold any pictures of the building if they had not printed slave market under their creations. Tourists now visit this spot, with their feelings in a sympathetic condition, for the cruelties that circle around these artistic columns, where only food was sold, under certain regulations, some of which we have copied from the original records.56Letter to the editor, St Augustine News, Saturday September 24, 1898. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library.

|  |

| Figure 48. William Henry Jackson, The Slave Market, St. Augustine, Fla., c. 1904. Collection of the Author. Created for the Detroit Publishing Company, the image, like Figure 45 above, depicts a lone figure idling beside the empty market. | Figure 49. William Henry Jackson, The Slave Market, St. Augustine, Fla., c. 1902. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-D4-9102. |

With his postcard, W. J. Harris was not the only photographer to capitalize on the site's cruel past. An English immigrant raised in Pennsylvania, Harris did not arrive in St. Augustine until 1898. A contemporaneous image created by photographer William Henry Jackson for the Detroit Publishing Company also depicts a lone figure idling beside the empty market (Figure 48). With utility poles and nearby buildings removed, and clearly labeled "slave market," Jackson's glass negative (now in the Library of Congress) became a mass-produced color postcard (Figure 49). The figure—a Caucasian man wearing a suit and hat with his hand touching his chin in thought—is almost imperceptible at first glance, blending into the background foliage. In contrast Harris's "old slave" presents a sharp outline against the manicured lawn and white pillar. As Roland Barthes points out, photographs confirm both death (what you see in the photograph is a moment from the past, never to return) and life (the moment exists, in the image, for eternity).57Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 5, 77. Accordingly, Harris's old slave is relegated to the past, yet his presence haunts this location and image. The 3½ by 5½ inch colored cardboard testifies that human enslavement occurred in this place now visited for pleasure.

|  |

| Figure 50. The Rotograph Co., Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Fla., c. 1909, recto. Collection of the Author. | Figure 51. Duval News Company, Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Fla., Oldest City in the United States, c. 1915, recto. Collection of the Author. |

Other versions of the "slave market" postcard, adopting Harris's general vantage point and caption, reveal the pavilion's different uses by Gilded Age tourists. A postcard stamped 1909 depicts the market in a grimier state (dirt visible on the masonry pillars) and an empty basket (abandoned by Harris's "old man"?) lying unused near the front steps (Figure 50). The utility pole in the foreground suggests growing modernity, while visitors with downcast faces occupy the dark interior of the market stall. They peer into a wishing well installed in an attempt to remove the "slave market" stigma. Benches and chairs offer shade. Local belief held that visitors who drank from the fountain were destined to return to St. Augustine.58David Nolan, e-mail message to author, March 20, 2012.

A slightly later postcard also re-imagines the site as a picturesque leisure plaza (Figure 51). Azaleas nestle the walls. Tables and chairs draw visitors. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century men playing checkers met at the market.59"Public Amusement for Visitors," The St. Augustine Evening Record, December 6, 1915, 4. Photographs from the 1880s and 1890s reveal inside tables. The air-conditioned restaurant (at right) and the public band shell and tile-roofed gazebo (at left) offer amenities. Live oaks and a wrought-iron lamppost complete the charm.

As portable objects, postcards acquire meanings as owners use, store, and manipulate them.60Glen Willumson and Alison Nordstrom discuss the importance of tracing the "trajectory" of an object through time in Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, eds., Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images (London: Routledge, 2004). Entrepreneurs sold postcards of St. Augustine's "slave market" to entice curious northerners and reassure anxious southerners. Postcards from other cities similarly promoted their slave markets as tourist attractions, often with as conflicting historical and imaginary meanings as those of Harris, presenting architectural relics of slavery as clean, picturesque, and inviting.

|

| Figure 52. Louisville Drug Co., Old Slave Market, Built 1758, Louisville, Ga., c. 1930. Collection of the Author. |

Louisville, a former capitol of Georgia, houses a market pavilion, once used to sell slaves, in its town center. Built in the late 1700s, the wood-beamed and shingled structure has been reconstructed and repaired over the years. While the Louisville market was undisputedly used for slave sales and commonly called the "slave market," civic officials have de-emphasized this use and the building is now officially referred to as the "market house."

Replacing an earlier sign titled "slave market," a 1979 marker in Louisville lists "slaves" as one more commercial item in addition to goods and land tracts. As in St. Augustine, the history of enslavement at Louisville's market is underplayed both in contemporary conversation and in vintage postcards. An early twentieth century postcard illustrates the cheerful market adorned with flowers at a quiet intersection (Figure 52). The verso text begins, "Built in 1758, the only Slave Market in America is pictured on the reverse side." Both facts—the construction date and uniqueness of the building—are inaccurate.61The Louisville, St. Augustine, and Charleston slave markets are three of many US sites once used to hold slave sales. At each location, debate persists about what to call these structures and how to commemorate their history. This debate is not unique to the South; many northern sites hosted slave sales. As Robert Desrochers notes, "Boston, the hub of the slave trade and much else in colonial Massachusetts, never had a single slave marketplace. It had many." Robert Desrochers, Jr., "Slave-For-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704–1781" William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 626.

|

| Figure 53. Paul E. Trouche, Publisher, Old Slave Market, Charleston, S.C., c. 1930. Collection of the Author. |

Charleston, South Carolina's "old slave market" appeared often in postcards, advertising "one of the many interesting relics from the days of slavery" (Figure 53).62Text on postcard's verso. The Charleston site hosted slave auctions, yet it remains at the center of a dispute over what to call it. Maurie McInnis explains that while "The Mart" on Chalmers Street in Charleston was specifically built for slave auctions, numerous articles nonetheless "tried to 'deny there existed sufficient buying and selling of slaves in the city to have warranted the establishment of any institution for that purpose.'"63McInnis, 220. Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). In this postcard, the slave market fills the frame, presenting an imposing façade, like an armory or jail.64World of a Slave, an encyclopedia of slavery's material culture, assesses Charleston's Slave Mart building and other slave markets as "slave jails." Martha B. Katz-Hyman and Kym S. Rice, eds., World of a Slave (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2011), 463–468. Charles Carleton Coffin, war correspondent for the Boston Daily Journal, wrote an account of the Charleston Slave Mart on February 17, 1865, referring to it as a "prison." The clean storefront, with an arched doorway framed by octagonal piers, appears sturdy enough to have held slaves.

Postcards bearing "slave market" helped establish St. Augustine's old pavilion as a symbol of racism and helped galvanize civil rights activists to make it a site for demands for desegregation and racial equality. The "St Augustine Movement" of 1963–1964 directed national attention to the brutal effects of segregation in Florida and contributed directly to the signing of the Civil Rights Act in June 1964.65Warren, If it Takes All Summer; David R. Colburn, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine Florida, 1877–1980 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1991). Films chronicling the St. Augustine movement include C. B. Hackworth, dir., Crossing in St. Augustine (2011); Clennon King, dir., Slave Market Diary (2004); and St. Augustine Department of Police, prod., St. Augustine Race Riots (1964), Florida State Archives. In 1963, local dentist Dr. Robert Hayling organized the Youth Council of St. Augustine's NAACP chapter. As St. Augustine prepared for its 1965 four-hundredth birthday, the town's Quadricentennial Commission organized a dinner at the Ponce de Leon hotel hosting President Lyndon Johnson. The guest list of local luminaries failed to include any African Americans. Hayling and other NAACP activists including Clyde Jenkins, James Jackson, and James Hauser organized nonviolent demonstrations over the next year. Local youths were arrested during a 1963 sit-in at the Woolworth's lunch counter on King Street adjacent to the "slave market." In 1964 northern college students traveled to St. Augustine for a spring break protest. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited at Hayling's request and was arrested for trying to eat lunch at the Monson Motor Lodge restaurant, one block north of the "slave market." Police thwarted attempts to integrate St. Augustine's beaches on Anastasia Island, and a "swim-in" at the Monson ended when hotel owner James Brock poured acid into the demonstrator-filled pool. Images of confrontations between protestors and segregationists provoked national outrage. The US Senate passed the Civil Rights Act two weeks later (Figure 54).66Ninety Associated Press photographs of civil rights demonstrations in St. Augustine are available available at "AP Photos Of 1964 Civil Rights Protests," The St. Augustine Record, accessed March 30, 2012, http://spotted.staugustine.com/galleries/index.php?id=335043.

|  |  |

| Figures 54–56. Figure 54. Segregationists trying to prevent blacks from swimming at a "white only" beach in St. Augustine, St. Augustine, Florida, 1964. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida. Figure 55. Civil Rights demonstrations around the "slave market," St. Augustine, Florida, 1964. Copyright Associated Press. Figure 56. Reverend Charles Conley "Connie" Lynch in the "slave market," St. Augustine, Florida, 1964. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida. | ||

Throughout the summer of 1964, demonstrators circled the "slave market" on daily marches down King Street.67King Street received its name much earlier. Segregationists also seized upon the site, verbally assaulting and brutally beating marchers (including Andrew Young).68Other organizers for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) present at the demonstrations included Ralph Abernathy, Willie Bolden, Dorothy Cotton, J. T. Johnson, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Hosea Williams. Photographs locate the plaza as a site of repression and resistance. In one (Figure 55), a young black man's sign reads, "Are you proud of your 400 yrs. history of slavery and segregation." A white woman behind him vows, "Until St. Augustine is desegregated tourists will demonstrate." White men in shirtsleeves play checkers. Just left of the central demonstrator is the 1930 "slave market" plaque. At night, segregationists occupied the market, physically and verbally attacking the marchers. St. Augustine became a hub of racist resistance. California Reverend Charles Conley "Connie" Lynch, along with Jesse Benjamin "J. B." Stoner, delivered nightly diatribes under the market's roof.69Wyn Craig Wade, The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 325. Rev. Lynch stands on a table clapping and grinning (Figure 56). The low vantage point positions him as the pinnacle of a pyramid made up of two young boys and a megaphone at the base and a Confederate flag at right. Electric lights installed by police illuminate the scene; the frenzied look on Lynch's face contrasts with the quiet boys. After being continually arrested, insulted, and assaulted, the marchers gained public sympathy. While not as well known as those of other cities, the civil rights demonstrations in St. Augustine, situated at the "slave market," were crucial to the movement's success.

A Place to Memorialize Enslavement

The monuments commemorating the Foot Soldiers and Andrew Young construct new layers of meaning for the Plaza de la Constitución, yet the site is rarely labeled on tourist maps and goes largely unnoticed by sightseers, even as the nearby streets of the Colonial Spanish Quarter are constantly full.

The denial of slavery at the market has remained a common refrain. As recently as 1986 St. Augustine Mayor Kenneth Beeson stated, "as far as our manuscripts indicate, no slave was ever sold there."70Jackie Feagin, The St. Augustine Record, January 22, 1986. Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. Beeson's comments provoked an outcry. St. Augustine historian David Nolan published articles detailing the historical slave transactions at the site.71Nolan, "Slaves Were Sold in Plaza Market." Margo Pope, "St. Augustine Once a Hub of Slave Trade" The Florida Times Union, December 2, 2001. Still, citizens disagree about what to call the market and how it should be used.72Historian Ralph Voss stated in 1984, "After digesting data from the library files, one question was answered. Slaves were DEFINITELY sold in the public market. But did that make it a slave market. That question is still open for debate." Ralph A. Voss, "Slave Market," North Florida Living, August 1984, 34–35.

In 2009, at the request of black history advocates, historian, teacher, and tour guide Amy Howard wrote a history of the public market for the tourism website augustine.com. Howard assesses three constituencies who disagree over the market's name and legacy. Most locals who use the term "slave market," writes Howard, "have little knowledge of the history, but have grown up with that name."73Amy Howard, e-mail message to author, March 23, 2012. Proponents of black history also use "slave market" because they protest "Black oppression getting swept under the rug. They bristle at people who say there was never a slave market in St. Augustine."74Ibid.; Karen Harvey, "Letter: 'Slave Market' is Part of City's Civil Rights History," The St. Augustine Record, November 1, 2007. The term "public market" tends to be favored by "heritage tourism advocates" who lament

racism threatening the city's image. Ever since Henry Flagler came along, the town has clung to tourism as its life blood. In the early tourism heydays, slavery was a marketable story. During and after the civil rights movement, racism became a scourge on the town. Now we have intellectuals trying to market the history, and doing their best to deny the . . . racism that still lingers today.75Howard, e-mail.

Howard E. Lewis, proprietor of St. Augustine's Black History Tours (a local walking tour company) agrees that while most locals use the terms "slave market" and "public market" interchangeably, black history advocates do not want the memory of slaves at the market to be forgotten, and "heritage tourism" promoters would rather not refer to slavery every time they mention the market.76Howard E. Lewis, nterview with the author, March 22, 2012. Information on Lewis' tours is found at "St. Augustine Black History Tours," accessed April 1, 2012, http://augustine.com/vacation/business/st_augustine_black_history_tours. Local historian Lewis writes St. Augustine history and tourism articles for Examiner.com.

As St. Augustine prepares for its 450th anniversary in 2015, government and civic organizations are planning projects, festivals, and events. The presidentially appointed "Federal Commission" of city organizers includes Andrew Young as well as St. Augustine's mayor Joseph Boles.77The official website for the St. Augustine 450th Commemoration is "St. Augustine 1565–2015," accessed March 30, 2012, https://sites.google.com/site/staugustine450/. A central goal is to integrate St. Augustine's histories of slavery and of civil rights into the larger narratives of colonial history and civic pride. Organizers responsible for installing the Foot Soldiers monument have chosen as their next goal the construction of a civil rights museum in this only major battleground city without one.78The non-profit organization Civil Rights Museum of St. Augustine, Inc. is planning the museum. "CRM of St. Augustine," accessed April 1, 2012, http://civilrightsmuseumstaug.webs.com/; David Nolan, interview; Kim Severson, "New Museums to Shine a Spotlight on Civil Rights Era" The New York Times, February 20, 2012, A8. A statement of the proposal is at "CRM of St. Augustine."

Throughout the past five decades, residents and government leaders have proposed ways to reinvigorate the old marketplace, including leasing the site to vendors.79Rosemary Heffernan, "Market Proposal Taken Under Advisement by City Commission" The St. Augustine Record, July 29, 1980. The city's 450th anniversary offers a renewed opportunity to resurrect these calls and, most importantly, to recognize and remember slavery. The debate over what to call the pavilion—"slave market" or "public market"—reflects a deep, unsettling disagreement.80Scholarship on racial memory that informed this essay includes: Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson, eds., Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003); Bruce Baker, What Reconstruction Meant: Historical Mmory in the American South (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007); and Blain Roberts and Ethan J. Kytle, "Looking the Thing in the Face: Slavery, Race, and the Commemorative Landscape in Charleston, South Carolina, 1865–2010," Journal of Southern History LXXVIII, no. 3 (August 2012): 639–684. The market is a reminder that America's "first coast," the picturesque "land of flowers and tropical scenery" was a haven for the slave trade.

One successful example of utilizing a former slave market as a site of education and remembrance is the Chalmers Street Market in Charleston. Currently operating as the "Old Slave Mart Museum," Charleston's former slave auction gallery offers visitors a forthright account.81"The Old Slave Mart Museum," City of Charleston, SC, accessed August 20, 2012, http://www.charleston-sc.gov/dept/content.aspx?nid=1469. St. Augustine's "slave market" remains an ambiguous structure, its historic and present meaning muddled by conflicting public markers and contrasting popular opinion. Rather than skirting the problem of slavery, St. Augustine residents have an opportunity to create a public acknowledgement and discussion of the city's history.

Recommended Resources

Edwards, Elizabeth and Janice Hart. Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images. London: Routledge, 2004.

Gannon, Michael, ed. The New History of Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996.

Griffin, Patricia, ed. The Odyssey of an African Slave. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009.

Harris, J. Carver, ed. "The Public Market Place," El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 54 (October 1964): 1–18.

Johnson, Walter. Soul by Soul: Life inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

McInnis, Maurie. Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade. IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Phillips, Tom. The Postcard Century. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Links

Civil Rights Museum of St. Augustine

http://www.accordfreedomtrail.org/ACCORDCivilRightsMuseum.html.

Howard, Amy. "Public Market (Slave Market)."

http://www.augustine.com/history/black_history/slave_market/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | J. Gardner, letter to the editor, St. Augustine Record, July 14, 1914. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Dan R. Warren, If it Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine 1964 (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2008). |

| 3. | Michael Gannon, ed., The New History of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996). |

| 4. | Jerald Milanich, Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995). |

| 5. | Jane Landers, "Spanish Sanctuary: Fugitives in Florida, 1687–1790," Florida Historical Quarterly 62, no. 3 (1984); Jane Landers, ed., Against the Odds: Free Blacks in the Slave Societies of the America (London: Frank Cass, 1996); and Margo Pope, "Slavery and the Oldest City," The St. Augustine Record, December 2, 2001. |

| 6. | See Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995); and Jane Landers, "Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose: A Free Black Town in Spanish Colonial Florida," American Historical Review 95, no. 1 (Fall 1990). |

| 7. | For histories of black and indigenous cultures in the southeastern coast region, see Jane Landers, ed., The African American Heritage of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995); and Kathleen A. Deagan, "Mestizaje in Colonial St. Augustine," Ethnohistory 20, no. 1 (Winter 1973): 55–65. |

| 8. | David Nolan, "Lincolnville, once called 'Africa,' Developed Following Emancipation," The St. Augustine Record, February 23, 2004. |

| 9. | According to the Royal Ordinance, the plaza, surrounded by the most important governmental and ecclesiastical buildings, was to function as the principal recreational and meeting area. In 1598 Governor Gonzalo Mendez de Canzo wrote to the Spanish crown, "After my arrival I caused a market place to be established, where there would be weight and measure, which heretofore had been lacking." From the Florida Master Site File for the public market, found in the Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board Historic Properties Inventory Form. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 10. | J. Carver Harris, ed., "The Public Market Place," El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 54 (October 1964): 1–18. The Spanish previously used the market as a guardhouse. |

| 11. | In 1840 a commercial boat basin was created in Matanzas Bay to provide easier ship access to St. Augustine's port. The basin was filled in 1900 and a bridge has spanned the waterway between St. Augustine and Anastasia since 1985. The Bridge of Lions, still standing today, dates to 1927. |

| 12. | Photographers Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 13. | Harris, ed., "The Public Market Place." |

| 14. | St. Augustine's obelisk may be the only monument dedicated to the Spanish Constitution in the Western Hemisphere. "Art Images of Monument to the Spanish Constitution of 1812," The St. Augustine Record, September 8, 2011. |

| 15. | Founded in September 1866, the Ladies Memorial Society consisted of socially prominent white St. Augustine women, mostly wives and relatives of Confederate soldiers. |

| 16. | David Nolan, interview with the author, March 22, 2012; City Commission Meeting notes: "City of St. Augustine, Regular City Commission Meeting, April 27, 2009," accessed April 1, 2012, http://www.staugustinegovernment.com/your_government/documents/CCMinutes04.27.09.pdf. The racial population of St. Augustine has changed since the 1960s, with an influx of white notherners in the 1970s–1990s. Whereas the black population hovered around twenty-five percent in the 1960s, today it is below ten percent. Zach Gray, "Racism in St. Augustine, Not Just a Thing of the Past," Flagler College Gargoyle, April 26, 2012. |

| 17. | Joseph Boles, Jr. (speech, Foot Soldiers Monument dedication ceremony, St. Augustine, FL, May 14, 2011). |

| 18. | Young and other demonstrators referred to the public market as the "slave market." As he writes in his memoir, "The destination of the marches in St. Augustine was the old slave market, which was unfortunately drawing large crowds of unruly whites who gathered each night to harass, threaten, and sometimes strike out at marchers." Andrew Young, An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America (New York: Harper Collins, 1998), 291. |

| 19. | David Nolan, interview with the author, March 22, 2012. |

| 20. | For examples of the term "slave market" used prior to the 1880s, see Earnest A. Meyer, "Childhood Memories" reprinted in El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 44 (2007): 204, in which Meyer depicts the "slave market" dated 1875. An illustration in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper from May 1878 also depicts the "slave market." A portrait bust of female slave Nora August, inscribed in part, "purchased from the Market, St. Augustine, Florida April 17th 1860" is found in the sculpture collection at the Museum of the Confederacy, see Museum of the Confederacy, Before Freedom Came: African American Life in the Antebellum South (Richmond: Museum of the Confederacy and University of Virginia Press, 1991), cover, 8. |

| 21. | Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1909), 177, quoted in Len Gougeon, Virtue's Hero: Emerson, Antislavery, and Reform (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 33. Henry L. Richmond, "Ralph Waldo Emerson in Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly 18, no. 2 (October 1939): 75–93. |

| 22. | Gougeon, 33. |

| 23. | County Deed Book, 24, 126, 288. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. These slave sales and others are also documented in E. W. Lawson, "The Slave Market," Today in St. Augustine, May 21, 1939. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 24. | Auction advertisement from the East Florida Herald, October 31, 1827. Also recorded in Deed Book F, 394. |

| 25. | Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 26. | David Nolan, "Slaves Were Sold in Plaza Market," St. Augustine Record, September 27, 2009. |

| 27. | Griffin, Patricia, ed., The Odyssey of an African Slave (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009). |

| 28. | Walter Johnson's Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001) examines the New Orleans slave market, North America's largest, where over 100,000 slaves were sold. While the rate of exchange in New Orleans vastly exceeds that of St. Augustine, Johnson's account of slave narratives, slave-owner letters, and court records offers insight into the commercial exchanges and human lives in St. Augustine. |

| 29. | Patrons of Flagler's St. Augustine's hotels were wealthy white vacationers. Thomas Graham, Flagler's St. Augustine Hotels: The Ponce de Leon, the Alcazar, and the Casa Monica (Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 2004). |

| 30. | The Ponce de Leon Hotel, which opened to great fanfare in 1888, is now the home of Flagler College. The Alcazar now houses City Hall and the Lightner Museum. The Cordoba still operates as a hotel, renamed the Casa Monica. |

| 31. | The first artist in residence at the Ponce de Leon studios was Flagler's friend Martin Johnson Heade. Artists who depicted the public market in their paintings include William Staples Drown, Robert S. German, Frank Shapleigh, and Felix de Crano. Sarah Barghini, A Society of Painters: Flagler's St. Augustine Art Colony (Palm Beach, FL: Henry Morrison Flagler Museum, 1998). To view the paintings depicting the market, see Gary Libby, ed., Reflections: Paintings of Florida 1865–1965. From the Collection of Cici and Hyatt Brown (Daytona Beach, FL: Museum of Arts and Sciences, 2009); Gary Libby, ed., Celebrating Florida: Works from the Vickers Collection (Daytona Beach, FL: Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1995); and Maybelle Mann, Art in Florida 1564–1945 (Sarasota FL: Pineapple Press, 1999). |

| 32. | Tom Phillips, The Postcard Century (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000); Marian Klamkin, Picture Postcards (New York: Dodd and Mead, 1974). |

| 33. | Postcards promoting relics of slavery to tourists are not unique to St. Augustine; other slave market sites are discussed below. In addition, Jim Crow era postcards often depicted grotesque illustrations of racism and segregation such as lynching. For an extensive discussion of lynching postcards see Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). Wood notes that lynching postcards, like slave market postcards, "deemed these events both customary and spectacular." Inscribing and circulating lynching postcards "substantiate[d] white supremacist views," normalizing the inhuman practice and packaging it as entertainment. Wood, 108. The slave market postcards operate similarly, sanitizing the human slave trade into sentimental nostalgic keepsakes. George Fredrickson discusses the romantic image of blacks in The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914 (New York: Harper & Row, 1971). |

| 34. | Maurie McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 220. |

| 35. | Ibid. |

| 36. | Nina Silber, The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South: 1865–1900 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 67. |

| 37. | Ibid. |

| 38. | Ibid., 2. |

| 39. | Prior to 1912 the postcard appeared in black and white and was printed in color after 1912. Robert R. Goller, "North and South With W.J. Harris, Photographer," El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History 28 (1991): 38; Robert Bogdan and Todd Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 245. |

| 40. | Goller, 38. The text on the front of the postcard reads, "Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Florida." The verso text reads, "The old slave market in the east end of the Plaza is an interesting landmark of antebellum days. Built in 1840." A later version was amended to include on the reverse, "It was used as a public market in which slaves were occasionally sold. Old Slave in foreground." |

| 41. | Research at the St. Augustine Historical Society and conversations with Harris's daughter and granddaughter did not reveal any information on the identity of the man depicted in the postcard. |

| 42. | Leslie Goode, personal communication with the author, March 23, 2012. See also Leslie Goode, "Harris Pictures," accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.harrispictures.com/. Harris Pictures is authored and operated by Leslie Goode, great-granddaughter of W. J. Harris. Her business currently sells t-shirts, coffee mugs, calendars, posters, and key chains emblazoned with images from Harris's postcards of St. Augustine landmarks. |

| 43. | Nina Silber discusses how "Black people . . . assumed especially picturesque qualities" for northern tourists. Silber, 80. Susan Parker, "Was it a Public Market or a Slave Market?" The St. Augustine Record, October 28, 2007. Silber states "forgetfulness, not memory, appears to be the dominant theme of reunion culture." Silber 4. For further reading on "forgetfulness" and the historical memory of the Civil War, see David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 250–99. Blight characterizes the culture of forgetting as "reconciliationist." |

| 44. | Goller, 38. |

| 45. | Jackie Feagin, "Slave Market Tag Came from Huckster Trying to Promote Tourism" The St. Augustine Record, Saturday July 20, 1985, 10A. The interviews conducted on March 22, 2012 by the author with the following subjects were particularly helpful: Charles Tingley, Amy Howard, David Nolan, and Howard E. Lewis. See also Goller, 38–43. |

| 46. | Amy Howard, "Public Market (Slave Market)," published February 5, 2009, accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.augustine.com/history/black_history/slave_market/tourism.php. This article authored by historian and teacher Amy Howard details the history of the "slave market" and the chronology of slavery in St. Augustine. See also Goller 31. |

| 47. | Charles Tingley, interview with the author, March 22, 2012. According to Tingley, Reynolds was the first St. Augustine historian "to take the city's attractions to task"—including the "slave market" and "oldest house"—for historical claims. The Charles Bingham Reynolds papers are in the collection of the University of Florida Smathers Libraries, Special Area Studies Collections. Reynolds (1856–1940) was originally from New York and worked for a time as editor of Forest and Stream Magazine. He helped to form the Audubon Society and partnered with Ward G. Foster to publish commercial guidebooks. |

| 48. | Charles B. Reynolds, The Standard Guide to St. Augustine (St. Augustine, FL: E. H. Reynolds, 1892), 53-4. In addition to his "Standard Guide" Reynolds published the book Old Saint Augustine: A Story of Three Centuries (St. Augustine, FL: E. H. Reynolds, 1885). |

| 49. | Reynolds, Standard Guide, 54. |

| 50. | Ibid. |

| 51. | S. J. Whall, letter to Charles Reynolds, October 7, 1889. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 52. | Reynolds, 105. Advertisement for The Tattler in Reynolds's guide. The publication was "sold on trains, in the hotels, and on news stands." |

| 53. | Max Bloomfield, Bloomfield's Illustrated Historical Guide (St. Augustine, FL: Bloomfield, 1884), 30. |

| 54. | Born Mary Ann McDowell (1825–1891), Hardy married Sir Thomas Duffy Hardy, the Keeper of Her Majesty's Records. She published fourteen novels, some under the pseudnym Addlestone Hill. Hardy traveled to America between 1880 and 1881 with daughter Iza, also a novelist. See Helen C. Black, Notable Women Authors of the Day (London: McLaren, 1906), 198. |

| 55. | Lady Duffus Hardy, Down South (London: Chapman and Hill, 1883), 171–72. |

| 56. | Letter to the editor, St Augustine News, Saturday September 24, 1898. Public Market Clippings File, St. Augustine Historical Society Research Library. |

| 57. | Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 5, 77. |

| 58. | David Nolan, e-mail message to author, March 20, 2012. |

| 59. | "Public Amusement for Visitors," The St. Augustine Evening Record, December 6, 1915, 4. Photographs from the 1880s and 1890s reveal inside tables. |

| 60. | Glen Willumson and Alison Nordstrom discuss the importance of tracing the "trajectory" of an object through time in Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, eds., Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images (London: Routledge, 2004). |

| 61. | The Louisville, St. Augustine, and Charleston slave markets are three of many US sites once used to hold slave sales. At each location, debate persists about what to call these structures and how to commemorate their history. This debate is not unique to the South; many northern sites hosted slave sales. As Robert Desrochers notes, "Boston, the hub of the slave trade and much else in colonial Massachusetts, never had a single slave marketplace. It had many." Robert Desrochers, Jr., "Slave-For-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704–1781" William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 626. |