Overview

Patricia Yaeger applies her passion for luminous trash to interpreting an epic film about toxic inequality, the southern imaginary, and the possibilities of mythmaking for the twenty-first century.

Review

I adored Beasts of the Southern Wild and have seen it three times: each viewing a quick incursion into the southern surreal. Benh Zeitlin's movie has received a nomination for best film, and Quvenzhané Wallis, his spunky, firebreathing star, may be crowned best actress. In the movie she plays the part of one of Louisiana's Katrina-surviving, throwaway children, but on her own terms she is a gargantua. The poster for the film shows the actress in darkness—her legs striding the ground, arms reaching out like Leonardo's Vitruvian Man and in each hand a giant sparkler irradiating the movie's title in untamable light.

|

| Film poster for Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

My present passion is luminous trash, glowing debris, garbage that lights up—like the tossed-away sled at the end of Citizen Kane or the illuminated basketball hoops that David Hammons makes out of Harlem debris or the bright garbage that a dirty robot collects in Wall-E. Beasts is a movie where debris and light vie for screen time. The heroine, Hushpuppy, is covered with mud as she traverses the squishy soil around her claptrap, rickety house. In the film's opening scenes the screen floods with light when the Bathtub's bright revelry spills over and neons the Cineplex audience. This film carries the nation's baggage; it investigates a culture of racial neglect, creates a zone of history-making for Katrina's disposable bodies, and provides a steady critique of white capital. The film's rags and wastelands—its killing fields—become powerful emblems of the Southland's (and our nation's) commitment to toxic inequality.

But something else rages in this film; it refuses the realism of social critique and advances instead into hubris land, into a new realm of myth making for the twenty-first century. "We's who the earth is for," boasts Hushpuppy, echoing her father's view of the racially mixed population of the Bathtub. This community bristles with carnivores, meat-eating women and men unashamed of their appetites, alcohol, and impoverishment. Nurtured, imperiled, the child creates a wild set of gods: demiurges, mother figures, aurochs, and sirens to inhabit a world dangerous and ecstatic. She forces us to ask: what myths do we need to live in an era of global warming where every coastal community may soon look like the Bathtub? As Zeitlin said of Isle de Jean Charles, the place where Beasts was filmed: "it's a place where ingenuity rules. Planks, low-lying bridges make up the walkways from house to house, so if your bridge gets knocked out, you fill the gap with a mattress or roofing."1Emily Brennan, "A Filmmaker's Lessons From the Bayou," The New York Times, August 16, 2012, Tr 3. Quvenzhané Wallis deserves an Academy Award because her impassioned presence and plain speaking bestow an unexpected path for assessing the mess we have made; her measured voice endows the film with a new mythos that addresses a world we have broken: a human cosmos that may be dirtied beyond repair.

Where to begin? Charles Wright's poem "In Praise of Thomas Hardy" takes us straight to the heart of light, dirt, and their relation to energy:

Each second the Earth is struck hard

by four and a half pounds of sunlight.

Each second.

Try to imagine that.

No wonder deep shade is what the soul longs for,

And not, as we always thought, the light.

No wonder the inner life is dark.2Charles Wright, "In Praise of Thomas Hardy," in A Short History of the Shadow (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2002), 27.

|

| Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

Beasts of the Southern Wild is about this four and a half pounds of sunlight. What happens when we take it for granted? What happens as we unravel the fabric of the universe by throwing two and a half centuries of fossil fuel back at the sun?

Beasts begins with a child making a dirt nest for a half grown chick, reminding us that even though primates may have started in the treetops, our home is in the dirt. This mud nest is small, lopsided, and looks uncomfortable, like a practice run for that other dirt-obsessed movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But instead of conjuring light-hungry aliens who come to earth, the nest-building child picks up the chick and listens to its heart; she imagines a chorus of animals: "'I'm hungry. I want to poop.' But sometimes they start talking in codes." How do we make our way into the coded life of other species? In Beasts meat is never processed and prepackaged; it always comes on the bone or in the shell—a reminder of its origins inside other creatures. "Meat is the buffet of the universe," Hushpuppy 's teacher insists. Hushpuppy's father reminds her: "Share with the dog," as if our main task in the Anthropocene, this new era when humans must learn to see themselves as a geologic force preying on the planet, is to know ourselves as a species dependent on other species. As Dipesh Chakrabarty suggests in "The Climate of History": "Changing the climate, increasingly not only the average temperature of the planet but also the acidity and level of the oceans, and destroying the food chain are actions that cannot be in the interest of our lives."3Dipesh Chakrabarty, "The Climate of History: Four Theses," Critical Inquiry 35 (Winter 2009): 219. Or as Hushpuppy says in the trailer: "The whole universe depends on everything fitting together. If one piece busts, even a small piece, the entire universe will get busted."

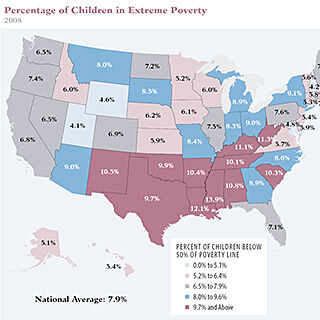

The vulnerability at the heart of Beasts is staggering. We should have created a planet where children can be safe, but we have not. One in ten American children live in deep poverty; 2.8 million children live in households that have incomes of less than two dollars per person per day—a benchmark for developing countries.4 Paul Tough, "The Birthplace of Obama the Politician," New York Times Magazine, August 19, 2012, 31. Peter J. Hotez, "Tropical Diseases: The New Plague of Poverty," New York Times, Saturday Review, August 19, 2012. Hushpuppy steers through her world in underpants, wearing white plastic boots covered in mud, her parents lost, the camera lens that follows her scratched or marred. She jousts perilously with sparklers; she lights a gas range and burns down her house; neglected and feisty, she is more wild than free, and her thoughtful face summons archetypes of abandonment.

|

| Quvenzhané Wallis as Hushpuppy. Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

Hushpuppy's near nakedness stirs the film's controversy. Author bell hooks protests oppressive stereotypes that ensure Hushpuppy's victim status and her father's abusiveness and cruelty: his life of drunken delirium. Arlene Keizer, a scholar of African American literature, noted in conversation that Zeitlin's film luxuriates in dirt, disorder, and mental disturbance—as if these were the exclusive properties of the racialized poor. Even the actress who plays Hushpuppy, Quvenzhané Wallis, insists in an interview with Oprah that the heroine should have been allowed to wear long pants. Were the filmmakers conscious of tapping these reservoirs of stereotypical abjection? Why summon inaccurate, dirty cliches about the hopeless lot of underclass blacks, Louisiana, and the marginal Southland, so blindly?

I want to argue that these criticisms, while eloquent, are off the mark. Beasts is not a slice of life or a realist screed; its business is mythological: it proffers a sacred narrative with overtones of awe and cosmic investigation. Querying the social order, it offers strange pedagogies about how we should live in a melting world. Hushpuppy equals the Invisible Man as a "thinker-tinker," a philosopher child who makes up her own world of demiurges and deities; she imagines calving glaciers, starry mothers, and glistening aurochs who want to gobble up cave babies, and in the process she creates creatures so scary and risible that we almost forget their filmic source—a handful of potbelly pigs blown up by the camera and turned into primeval beasts with a patchwork of nutria fur and tacked-on tusks—the bricolage of an odd filmmaker and an even odder child's imagination.

Beasts works through two additional forms of myth making. First, while Hushpuppy's father Wink is scary, he also has a vitality so palpable that his daughter has to absorb it. "Who de man?" he shouts. "I the Man!" she replies. In a scene where one of the white men in her community is teaching Hushpuppy how to eat crab with a knife (and standing suggestively behind her, reminding us of Hushpuppy's sexual vulnerability once her father dies), Wink insists that she "beast it": she must break the crab open with her bare hands and suck its guts out by sheer force of will. Her father may be helpless against the curse of alcohol, but he provides her with meat, with safety from other men (including himself, since he insists that they live in separate houses), and he inhabits the mythic register of the Fisher King, a wounded monarch whose sickness unto death puts his entire kingdom in jeopardy—a wild lord who must be restored to health, or replaced, if the wasteland is to flourish. And in the final scenes Hushpuppy hews to this myth by bringing him a bizarre magic chalice—the closest thing to a talisman that the commodity world owns—a throwaway Styrofoam container filled with gator meat fried by her knife-wielding, light-creating, imaginary mom. The wasteland is with us now and forever—even its myths create trash.

|

| Hushpuppy and Wink, played by Dwight Henry. Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

This throwaway Styrofoam brings us to Beasts' other mythic register—its quest for a way to represent our species' relation to global warming. Styrofoam is made from oil, and images of acetylene torches, gas stoves, and gas engines remind us that although the film's characters are battered by the forces of global warming and their carbon footprint is small, creating a carbon-free democracy is not their concern. The citizens of the Bathtub practice a dirty ecology, making do with what they can salvage from other waste-making classes. When a Katrina-like storm savages their community, the damage is endless. A giant pig-beast knocks over power lines: these are animals who "eat their own mommas and daddies." In the Bathtub the carbon apocalypse is already upon us. Early in the movie, Hushpuppy's teacher raises her skirt; she shows a thigh tattooed with prehistoric aurochs—"fierce" creatures who signify that "any day the fabric of the universe is going to unravel." A blast of poverty consumes everyone living in Wink's and Hushpuppy's community. After we watch the child, her father, and their chickens, dog, and pig chew up the world during a ritual "feed-up time," the film veers from animal eating to the screen-filling shot of an oil refinery. "Ain't that ugly over there?" Wink says from his repurposed boat. "We got the prettiest place on earth." The Bathtub's houses are made from castaway metal and lumber, its people jettisoned by the currents of capitalism. It's too close to the water: cut off by a levy from the thing-creating world. The oil refinery looks at once mechanical and auratic; its white spires hover in the same place in the pictorial frame as the calving glaciers that start to rain down on the audience, and free child-eating aurochs—the mythic equivalents of carbon's rough beasts, their hour come round at last.

These once-extinct, returning aurochs mark the movie's geologic concern, its interest in eras. Around 1750, humans switched from renewable energy to the large-scale use of fossil fuel—a shift in scale marking the beginning of a new era.5Chakrabarty, 207. Ten thousand years ago the Pleistocene or Ice Age gave way to the warmer Holocene, and civilization began in earnest. But our contemporary era, the Anthropocene, has speeded up our species' access to matter until we now create our own weather events, our own set of fractures. Humans are reborn as geologic agents, as the main cause of change for earth itself. Chakrabarty argues that humans now wield a separate geological force and that we must scale up our imagination of the human, the consciousness of our scope and reach as species being, before we can hope to redeem the planet.6Chakrabarty, 206. This means owning up to the imbroglios we have made, and their unintended consequences. Claiming these unintended consequences becomes Hushpuppy's lament, her motif in Beasts. Angry at her father for going away (near the beginning of the film we see him wandering toward the house, dazed, in a hospital gown; he's been institutionalized against his will for delirium tremens brought on by heavy drinking), she sasses him and he strikes her. She then strikes him back, and he goes down—a man of great will but little strength. The screen flashes with visions of glaciers melting; Hushpuppy transfers her teacher's parable onto her father's ruined body: fantasizing that he is a landscape her bad actions have broken. She dashes to get him medicine and he disappears again, only to reappear as the heavens open: a hurricane nears. Like Lear, Hushpuppy takes the force of the gathering storm upon herself, calling into the wind: "Momma, is that you? I've broken everything."

This is primitive thinking—an animistic sense that her actions have caused the decay of the universe. It is mistaken, childish—and may suggest a deep psychological wound. Children reeling from abuse may internalize themselves as bad objects, blaming themselves because it's too painful—too dangerous—to jeopardize a precarious relationship with their parents. To decide that she is at fault, that she's done the breaking, puts Hushpuppy in a universe of children who've been neglected or traumatized. She blames the world's trauma on herself to keep from alienating her caretaker—a father so unpredictable that even a child's feathery anger might frighten him away. Self accusation makes sense in terms of the film's psychological economy, but it also operates in a mythical or cosmic register.

According to Chakrabarty, Bruno Latour, Tim Mitchell—or a thousand ecologists—the guilty recognition that we have the power to shatter our own universe is exactly the tragic recognition—a true anagnorisis—that we need to embrace; we need to scale up not only our self-knowledge, but our self-image as quasi-subjects with the terrible power to change the planet, not just individually, but as species-being. Beasts names us as a vulnerable species in need of tools that can mirror and refract the depth of our ongoing, entangled acts of pollution, our attachment to things that keep turning into debris, our power to destroy Earth itself. Hushpuppy's animistic thinking is a mistake, but this displacement is also a powerful origin point for a necessary myth, for the dream we need to dream (that is, to make into creed, to make tangible) of our complicity as a dangerous, polluting species.

|

| Wink and Hushpuppy. Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

I'm arguing that Hushpuppy signals to us, again and again, possible transference points for claiming kin with our carbon voracity. First, she's a determined creatrix who tries to memorialize her own acts of trashing: "If Daddy kill me [for burning down the house] I ain't going to be forgotten," she thinks and hides under a cardboard box while the flames advance as she draws a picture of herself for posterity. "Daddy could have turned into a tree or a bug," she thinks when he disappears, "there wasn't any way to know," and the screen flashes with tent caterpillars and ice floes suggesting the break-up of the universe. When the hurricane rages we see mud-spattered animals trudge through the needling rain. When it's over and Hushpuppy and Wink float in their newly drowned world, Hushpuppy thinks of the waste of dead animals: "They're all down below trying to breathe through the water. For animals that didn't have a Dad to put them in the boat, the end of the world already happened." When the water finally drains out of the Bathtub, Hushpuppy reminds us: "It didn't matter that the water was gone. Sometimes you can break something so bad that it can't be put back together." Or, watching her father die, she exclaims, "The brave ones stay and watch it happen. They don't run," but she still finds herself on a boat skippered by a captain who hoards all his Chick-fil-A wrappers: "the smell helps me to be cohesive." Garbage animates this wasteland, but as the movie veers away from a world filled with animal parts—and unabashed human carnivores who lie down in mounds of crawfish shells or sleep in piles of rags and throw-away clothing that, to bourgeois noses, would smell unclean—it embraces a comedy of processed food that seems to grow its own trash, and Hushpuppy insists that you still have to "fix what you can."

|

| Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

In Beasts nothing gets mended, except for the audience's amazement at a child's voracious imagination. After the apocalypse, those left in the Bathtub try to drain the polluting water by detonating a levy. The screen goes white when the detonation is successful, and then reveals barren bayous. Hushpuppy's community is forced to go to the "Open Arms Processing Center," a sterile, inhospitable world where "when an animal gets sick here they plug it into the wall." The film starts to fall apart in this civilized bureaucracy. Hushpuppy's imagination slows down, and Zeitlin falters as his mythic backdrop falls away. The film finally picks up when it returns to the wasteland, although it makes a second detour to a buoyant island of happy prostitutes. This detour from carbon catastrophe is beautiful; the screen dazzles with utopian lights that reiterate, in a vague and careless way, a wished-for matriarchy. At the end of this scene little girls dance with loving women wearing old-fashioned white slips—as if the movie wants to promise us a Land of Cockaigne where little girls will always be sexually safe, where mothers can be cooks instead of hookers, and where heat and light are endless.

To return to life as an endangered child in a universe of bureaucracy and endless waste is scary. But the ritual death of the Fisher King, the film's insistence that Hushuppy's father must die and cannot heal the wasteland, keeps us mired in the film's litany of Anthropocene images. Allan Stoekl argues that every twenty-first century addiction flows from our addiction to oil.7Allan Stoekl, Bataille's Peak: Energy, Religion, and Postsustainability (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). To break this obsession means reformulating our entire subjectivity.

To prevent this, we practice a dirty ecology: recycling a few things while leaking and expending everything else. In other words, dirty ecology is the science of halfway practices. We know that driving and flying and industrial pollution and living in drywall houses destroys the planet, but we continue to do it. Hushpuppy appeals so powerfully because she is an early avatar of who we need to become: a child who clings to Styrofoam but sends her liquor-addicted dead father in his gasoline-addicted-repurposed-Chevy truck-made-into-a-boat off into another world.

|

| Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012. |

Hushpuppy's cry keeps echoing: "Momma . . . I've broken everything!" Her mythical thinking represents childish animism and a private legacy of psychological damage. But myths also establish long-term models for guiding behavior. They require, first of all, mystery—awe at fact of the universe and our place in it; second, a topos—an explication of cosmic shape that can ground us in a felt geography; third, an epistemology—shaping foundations supported by codes or ideas that establish the norms of the social order; and finally an ethic—a set of rules or maxims about how to live within the parameters of the everyday. Beasts bestows a weird movie mythopoeia for reestablishing each of these needs within our present era: the carbon-drunk Anthropocene.

In this movie's wake, I hope for a long line of girls and boys who will call out to us with the knowledge that we've broken our ecosystem. We must dirty ecology, the science of whole environments, with myths, fictions, half-truths, dirty imagery. Myths are crucial as implements of attachment and ownership for all the unintended consequences we have to live with in order to make a buffet, a movable feast, and a pedagogy out of our cosmic impasse. "If daddy don't get back soon it will be time for me to eat my pets," Hushpuppy says early in the movie to soothe her growing sense of abandonment. Even though Wink imagines that "I got it under control," he also sees that "my blood is eating itself." No one has it under control in the Anthropocene, and unless we recognize this soon we will have to eat things stranger and less appetizing than our pets. What's the world coming to when the best movie of 2012 has a nutria rigger, when it reimagines extinct aurochs as potbellied pigs with plastic horns? Beasts of the Southern Wild is whimsical, but it is also an epic comment on our condition of metamorphosis when humans persist in changing Earth's geologic direction: "Daddy could have turned into a tree or a bug, there wasn't any way to know." Trees and bugs may not need mythologies, but the rest of us do, and to advance the project of reshaping a planetary epistemology, see this movie—and then let's start to fix what we can.

About the Author

Patricia Yaeger is Henry Simmons Frieze Collegiate Chair at the University of Michigan. She was editor of PMLA from 2006–2011 and author of the award-winning Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing. She is working on two books: "Luminous Trash: America in an Age of Conspicuous Destruction" and "Flannery O'Connor in Drag," and is co-editing volumes on literature and energy, "Fueling Culture: Energy, History, Politics" and "American Dirt."

Cover Image Attribution:

Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild, Twentieth Century Fox, 2012.Recommended Resources

Allison, Dorothy. Bastard out of Carolina. New York: Plume, 1992.

Brennan, Emily. "A Filmmaker's Lessons From the Bayou." The New York Times, August 16, 2012, Tr 3.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. "The Climate of History: Four Theses." Critical Inquiry 35 (Winter 2009) 197–222.

Cox, Karen L. Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was Created in American Popular Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

———. "The South Ain't Just Whistlin' Dixie." The New York Times, September 17, 2011.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/18/opinion/sunday/the-south-aint-just-whistlin-dixie.html?pagewanted=all.

Dyson, Eric Michael. Come Hell or High Water: Hurricane Katrina and the Color of Disaster. New York: Basic Civitas, 2006.

Scott, A. O. "She's the Man of This Swamp." The New York Times, June 26, 2012. http://movies.nytimes.com/2012/06/27/movies/beasts-of-the-southern-wild-directed-by-benh-zeitlin.html.

Stoekl, Allan. Bataille's Peak: Energy, Religion, and Postsustainability. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Yaeger, Patricia. Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women's Writing, 1930–1990. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2000.

Links

Beasts of the Southern Wild Playlist, MFA FilmDistribution

http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLngZAJWTICfU6skjCA6DbYBAqjDrAeBho.

Beasts of the Southern Wild, Offical Website

http://www.beastsofthesouthernwild.com.

Before and After: 50 Years of Rising Tides and Sinking Marshes, PBS Newshour

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/multimedia/isle-de-jean-charles/.

Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

http://climate.nasa.gov.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Emily Brennan, "A Filmmaker's Lessons From the Bayou," The New York Times, August 16, 2012, Tr 3. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Charles Wright, "In Praise of Thomas Hardy," in A Short History of the Shadow (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2002), 27. |

| 3. | Dipesh Chakrabarty, "The Climate of History: Four Theses," Critical Inquiry 35 (Winter 2009): 219. |

| 4. | Paul Tough, "The Birthplace of Obama the Politician," New York Times Magazine, August 19, 2012, 31. Peter J. Hotez, "Tropical Diseases: The New Plague of Poverty," New York Times, Saturday Review, August 19, 2012. |

| 5. | Chakrabarty, 207. |

| 6. | Chakrabarty, 206. |

| 7. | Allan Stoekl, Bataille's Peak: Energy, Religion, and Postsustainability (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). |