Overview

|

| Stan Schnier, Women hold Mexican and American flags at the final Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride event, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, New York, New York, October 4, 2003. |

In the last two decades, immigrants, especially those from Latin America, have transformed key aspects of the US South. As recent Latino immigrants seek to make sense of their experiences in the South, they call into question how southern histories are mobilized to define and interpret the present, how southern pasts are rendered accessible and meaningful, and how new groups gain or lose legitimacy as “southern.” Through an analysis of three vignettes drawn from ongoing research on Latino migration to the South, this essay illustrates the entanglements of southern past, present, and future with the narratives of growing immigrant populations. Greater exchange between southern studies and studies of immigration, we suggest, can complicate the black-white racial binary through which “the South” has been represented and stabilized as a coherent and distinctive place. As Latino men and women create new mappings in and of the South, studies of Latino experiences help transform and enliven southern studies.

"New Pasts: Historicizing Immigration, Race, and Place in the South" was selected for the 2010 Southern Spaces series "Migration, Mobility, Exchange, and the US South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary scholarship about how the movements of individuals, populations, goods, and ideas shape dynamic spaces, cultures, and identities within or in circulation with the US South.

Introduction

In an elementary school in Nashville, Tennessee, Mexican children ask, “Where were the Hispanics with Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis?” An Egyptian girl at the same school wonders which water fountain she would have drunk from during Jim Crow. In Memphis, black political and business leaders invoke slavery’s legacy to reject Latino claims for minority set-asides in municipal contracts, arguing that Latinos’ recent arrival makes them no match for four-hundred years of black oppression. Across the US South, immigrant-advocacy groups borrow heavily, sometimes directly, from a civil rights playbook, mapping the 2003 Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride onto the original Freedom Ride and in 2006, rallying in spaces politically memorialized during the civil rights movement.

|

| Banner from the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride website, 2003. |

How do we make sense of these entanglements of a South contoured by a historical black-white binary, de-jure segregation and de-facto racism, and a South stretched into transnational flows of bodies, cultures, and capital? In the contemporary South, who can invoke and be part of its past, and to what ends? How do and should the interpretations of southern history affect present actions, and who can access these meanings to interpret and intervene in the present? These questions are pressing in the nuevo South, which has experienced rapid Latino population growth since the 1990s.1Although in this article, we focus on Latino migration (a ‘nuevo’ South), we acknowledge the presence of smaller immigrant and refugee populations, some of which have long histories in the South. These groups have impacted racial and social formations in some southern locales and are the subject of such recent studies as Mark Moberg and Stephen Thomas, “Indochinese Resettlement and the Transformation of Identities Along the Alabama Gulf Coast” and Choony Soon Kim, “Asian Adaptations in the American South,” in Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South: Anthropological Contributions to a Region in Transition, ed. Carole Hill and Patricia Beaver (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998); Deborah Duchon, “Home Is Where You Make It: Hmong Refugees in Georgia,” Urban Anthropology 26, no. 1 (1997): 71-92; David Reimers, “Asian Immigrants in the South,” in Globalization and the American South, ed. James Cobb and William Stueck (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005); and Jin-Kyung Yoo, “Utilization of Social Networks for Immigrant Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Korean Immigrants in the Atlanta Area,” International Review of Sociology 10, no. 3 (2000): 347-363. In a South where many argue the past is not dead or even past, how contemporary events are narrated through historical frameworks makes for contentious terrain. From southern history’s obsession with the Civil War to African American history’s extensive writings on Jim Crow and resistance, from debates about southern convergence with the nation to reflections on the South’s “recent” globalization, versions of the South's past are mobilized to interpret or challenge its present.2The reference to the “past isn’t dead” originates with Williams Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1951). For an academic examination of historical narratives that influence the present, see Ewen Hague et al., “Whiteness, Multiculturalism and Nationalist Appropriation of Celtic Culture: The Case of the League of the South and the Lega Nord,” Cultural Geographies 12, no. 2 (2005): 151-173. For a more popular approach to similar themes, see Jim Webb, Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (New York: Broadway Books, 2004). For discussions of the Civil War, see Curt Anders, Hearts in Conflict: A One-Volume History of the Civil War (Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub. Group, 1994). For discussions of African American history, see Kenneth Goings and Raymond Mohl, eds., The New African-American Urban History (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996). For discussions of the contemporary South and southern distinctiveness, see Larry Griffin and Don Doyle, eds., The South as an American Problem (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995); Dewey Grantham, The South in Modern America: A Region at Odds (New York: Harper Collins, 1994); and James Cobb and William Stueck, eds., Globalization and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

As the economies, populations, and cultural practices of southern states have “gone global”— from foreign direct investment to NASCAR to flexible labor—the framework that southern history offers for understanding the present has splintered, particularly vis-à-vis Latino migration.3Cobb and Stueck, Globalization and the American South; Barbara Ellen Smith, Marcela Mendoza, and David Ciscel, “‘The World on Time:’ Flexible Labor, New Immigrants and Global Logistics,” in The American South in a Global World, ed. James Peacock, Harry Watson and Carrie Matthews, 23-38 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005). As new immigrants seek a “usable past” within which to place and make sense of their experiences, they implicitly call into question how southern histories are mobilized to define and interpret the present, how specific southern pasts are rendered accessible and meaningful, and how new groups gain or lose legitimacy as “southern.”4Larry Griffin, Ranae Evenson, and Ashley Thompson, “Southerners All?,” Southern Cultures 11, no. 1 (2005): 6-25.

Drawing on more than ten years of research on community change, racial formations/politics, and immigration to southern cities and towns, we call for a deeper historicization of immigrant experiences and of responses to immigration.5See, for example, Barbara Ellen Smith and Jamie Winders, “‘We’re Here to Stay’: Economic Restructuring, Latino Migration, and Place-Making in the U.S. South,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 33 (2008): 60-72; Barbara Ellen Smith, “Across Races and Nations: Social Justice Organizing in the Transnational South,” in Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place, ed. Heather Smith and Owen Furuseth, 235-256 (Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006); Jamie Winders, “Changing Politics of Race and Region: Latino Migration to the U.S. South,” Progress in Human Geography 29, no. 6 (2005): 683-699; Jamie Winders, “‘New Americans’ in a ‘New South’ City? Immigrant and Refugee Politics in the Music City,” Social and Cultural Geography 7, no. 3 (2006): 421-435; and Jamie Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture? Race, Latino Migration, and Urban Politics in Nashville, Tennessee,” Urban Geography 29, no.3 (2008): 246-263. Historicization is key, since migration studies often treats immigration to the South as either so transformative that it replaces local and regional historical geographies of race, place, and labor or so different from past practices that no connection to them can be made. Much work in southern studies remains heavily influenced by black-white visions of the plantation South, Civil-War South, Jim-Crow South, and civil rights South, perspectives that render immigration invisible. Recent demographic reconfigurations of the South, however, call for new approaches to not only the South's present but also its past and future. Because of the tight riveting of race, place, and region in the South, a deeper historicization of immigration and responses to it can enliven southern studies through discussions about the racialization of new Latino populations.6An exception to the failure to historically contextualize immigration to the South is Rubén Hernández-León and Víctor Zúñiga, “Appalachia Meets Aztlán: Mexican Immigration and Inter-Group Relations in Dalton, Georgia,” in New Destinations of Mexican Immigration in the United States: Community Formation, Local Responses and Inter-Group Relations, ed. Víctor Zúñiga and Rubén Hernández-León, (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2005).

In this essay, we place southern studies alongside studies of immigration to the South, highlighting their disciplinary, methodological, empirical, and political differences. Although these fields have yet to speak to each other in sustained fashion, they are enmeshed in many southern locales. To illustrate this point, we discuss three moments in which the politics of an immigrant presence and a southern past entangle. We conclude by reflecting on how southern history is and is not put to work to understand and intervene in the politics of the nuevo South.

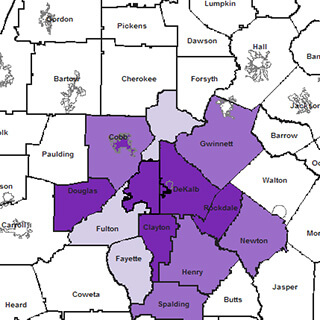

Re-visioning Southern Immigration

In the last two decades, the geography of Latino migration to and within the United States has become increasingly complex. What was once a phenomenon associated with gateway cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami, and New York has morphed into a national trend. In the South, Latino men and women from across the United States and Latin America have come for reasons ranging from debt crisis and peso devaluation in Mexico to civil unrest in parts of South America, from cooling economies and growing anti-immigrant sentiment in Texas and California to the pull of construction jobs for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Within southern locales, Latino communities are notable less for their size than for the speed at which they developed. Although small in comparison to Latino populations in gateway cities, since the 1990s the South’s Latino populations have been growing faster than in other areas of the country.7Richard Fry, Latino Settlement in the New Century, October 23, 2008 (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center), http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/96.pdf. For discussions of immigration to the South, see Carl Bankston III, “New People in the New South: An Overview of Southern Immigration,” Southern Cultures 13, no. 4 (2007): 24-44; Peacock, Watson and Matthews, eds., The American South in a Global World; Holly Barcus, “The Emergence of New Hispanic Settlement Patterns in Appalachia,” The Professional Geographer 59, no. 3 (2007): 298-315; Furuseth and Smith, Latinos in the New South; Zúñiga and Hernández-León, New Destinations; Helen Marrow, “New Destinations and the American Colour Line,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32, no. 6 (2009): 1037-1057; Benjamin Shultz, “Inside the Gilded Cage: The Lives of Latino Immigrant Males in Rural Central Kentucky,” Southeastern Geographer 48, no. 2 (2008): 201-218; Robert Yarbrough, “Latino/White and Latino/Black Segregation in the Southeastern United States: Findings from Census 2000,” Southeastern Geographer 43, no.2 (2003): 235-248; Fran Ansley and Jon Shefner, eds., Global Connections and Local Receptions: New Latino Immigration to the Southeastern US, (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009); and Douglas Massey, ed., New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration, (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008).

The broad contours of Latino population growth in the South are simple to document; but the processes and particularities of Latino migration are more complicated than aggregate statistics reveal. Latino migration includes documented and undocumented residents, US-born and foreign-born migrants, seasonal laborers who move among agricultural sites throughout the South and permanent residents who put down roots and begin families. Equally important, Latino populations, especially in southern cities, include men and women who have moved from other US cities, as well as individuals from across Mexico and many parts of Central and South America. In this way, while much commentary, academic or otherwise, discusses Latino/Hispanic migration or “the Hispanic/Latino community” in monolithic terms, there is much national, economic, political, and linguistic diversity among Latinos in the South.

Adding to this complexity is the uneven temporal and spatial dispersion of Latinos. Certain southern states, most notably Texas and Florida, have a longstanding Latino presence and influence. Among so-called “new destinations,” Georgia and North Carolina experienced Latino settlement and population growth before many other southern states and have been “ahead of the curve” in terms of local impacts of and responses to immigrant settlement. Latino migration became a notable trend in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama five to ten years later, as industries such as meat processing and the fast-food and hospitality sectors turned to immigrant labor. In the present economic recession, anecdotal evidence suggests that Latino migration to the South is waning but that return migration is not necessarily increasing. The trends we address in this article, thus, are not reversing, though the pace of immigration and character of immigrant settlement may be changing in ways not yet apparent.

|

| Stan Schnier, Immigrant workers at the final celebration of the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, New York, New York, October 4, 2003. |

Across southern spaces, Latino population growth has also been highly uneven. Until Hurricane Katrina and the need for cheap immigrant labor to rebuild New Orleans, for instance, Louisiana had little Latino population growth. Within the historic “Black Belt,” increase in the Latino population has been much smaller, raising questions about the links among race, poverty, and immigrant settlement across the South. Even in states that have notable Latino population increase, there are rural, urban, and suburban differences, with cities typically having a wider range of nationalities and occupational skills represented in their Latino populations. In the neighborhoods of small southern towns and rural areas, Latino residents often overlap more with long-term black and white residents than they do in southern cities, but are also more concentrated in one type of work, such as poultry processing or agriculture. Studying Latino migration to the South necessitates attending to a demographically, geographically, and temporally uneven phenomenon that has only recently come onto the radar of scholars of the South.8For work on Latino migration to the rural South, see Peter Benson, “El Campo: Faciality and Structural Violence in Farm Labor Camps,” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 4 (2008): 589-629; and Josh McDaniel and Vanessa Casanova, “Pines in Lines: Tree Planting, H2B Guest Workers, and Rural Poverty in Alabama.” Southern Rural Sociology 19, no.1 (2003): 73-96. For work on the geographic diversity of Latino migration to the South, see James Elliott and Marcel Ionescu, “Postwar Immigration to the Deep South Triad: What Can a Peripheral Region Tell Us About Immigrant Settlement and Employment?” Sociological Spectrum 23 (2003): 159-180; Laurel Fletcher et al., “Rebuilding after Katrina: A Population-Based Study of Labor and Human Rights in New Orleans.” International Human Rights Law Clinic, Boalt Hall School of Law, and Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, and Payson Center for International Development and Technology Transfer, Tulane University (June 2006). For work on Latino labor-market participation, see Steve Striffler, “Neither Here Nor There: Mexican Immigrant Workers and the Search for Home.” American Ethnologist 34, no.4 (2007): 674-688. For work on Latino migration to southern cities, see Qingfang Wang and Wei Li, “Entrepreneurship, Ethnicity and Local Contexts: Hispanic Entrepreneurs in Three U.S. Southern Metropolitan Areas,” GeoJournal 68 (2007): 167-182; Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?;” and Yarbrough, “Latino/White and Latino/Black Segregation.”

Although these changes are reconfiguring southern landscapes and social terrains, no one can deny the historical and on-going power of a black-white binary in contouring the South’s material and metaphoric spaces. How new immigrants alter this racial binary remains unclear, as does where the South itself fits in discussions of immigration. Many migration scholars argue that immigration has long shaped US racial/ethnic politics and cultural life, particularly within its cities.9Alejandro Portes and Alex Stepick, City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami (Berkeley: University of California, 1993); Rachel Buff, Immigration and the Political Economy of Home: West Indian Brooklyn and American Indian Minneapolis (Berkeley: University of California, 2001). Outside Florida and Texas, however, the South has been a space of exception, a place where national trends of immigrant settlement and labor have been presumed not to apply.10Jamie Winders and Barbara Ellen Smith, “Excepting/Accepting the South: New Geographies of Latino Migration, New Directions in Latino Studies.” Latino Studies, under review; and Susan Greenbaum, “Urban Immigrants in the South,” in Hill and Beaver, Cultural Diversity. For discussion of the South outside a black-white binary, see Rowland Berthoff, “Southern Attitudes Toward Immigration,1865-1914,” Journal of Southern History 17, no. 3 (1951): 328-360; Light Townsend Cummins, “The Hispanic Heritage of the Southern United States of America,” Revista de historia de America 10, no. 5 (1988): 89-110; and Julie Weise, “Mexican Nationalisms, Southern Racisms: Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the U.S. South,1908-1939,” American Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2008): 749-777. For discussion of immigration and US racial politics, see Gabriela Arrendondo, “Navigating Ethno-Racial Currents: Mexicans in Chicago,1919-1939,” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 3 (2004): 399-427; and James Barrett and David Roediger, “In-between Peoples: Race, Nationality, and the ‘New Immigrant’ Working Class,” Journal of American Ethnic History 16, no. 3 (1997): 3-44.

One of the challenges of historicizing immigration to southern locales, then, is the gap between southern studies and studies of immigration to southern locales, between work on the South's history, culture, and politics and work on its recent immigrants and their reception. Part of this gap reflects differences between the two fields. Much of southern studies emerges from the humanities. With strengths in textual studies, historical analysis, and material culture, southern studies utilizes related methodologies (e.g., literary criticism, archival investigation, musicology, and discourse analysis) to engage such topics as local and regional identities, cultural production, and the idea of the South itself (plantation South, the postbellum South, the segregated South, and so on) as objects of study. In contrast, studies of immigration to the South draw heavily from the social sciences, particularly geography, sociology, anthropology, and political science. Although some new work engages the cultural politics of immigration and identity in southern locales, most utilizes social-science methods such as surveys, participant observation, interviews, and secondary data analysis. Through these sorts of distinctions (which work more as heuristic devices than absolute differences), southern studies and studies of immigration to the South stabilize their objects of analyses in ways that further the gap between the two fields.11For works in southern studies, see Edward Ayers, “Narrating the New South,” The Journal of Southern History 61, no. 3 (1995): 555-566; Griffin and Doyle, The South as an American Problem, and Jennifer Rae Greeson, “The Figure of the South and the Nationalizing Imperatives of Early United States Literature,” The Yale Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (1999): 209-248. For works on southern immigration, see Carl Bankston III et al., Sociological Spectrum 23 (2003); Altha Cravey, “Desire, Work and Transnational Identity,” Ethnography 6, no. 3 (2005): 357-383; Arthur Murphy, Colleen Blanchard, and Jennifer Hill, eds., Latino Workers in the Contemporary South, (Athens: University of Georgia, 2001); Smith and Furuseth, Latinos in the New South; Winders, “Changing Politics of Race and Region”; Terry Easton, “Geographies of Hope and Despair: Atlanta’s African American, Latino, and White Day Laborers,” Southern Spaces, December 21, 2007. For engagement with the cultural politics of immigration to the South, see Mary Odem, “Our Lady of Guadalupe in the New South: Latino Immigrants and the Politics of Integration in the Catholic Church,” Journal of American Ethnic History 24, no. 1 (2004): 26-57; and also Mary Odem, Global Lives, Local Struggles: Latin American Immigrants in Atlanta,” Southern Spaces, May 19, 2006.

Southern studies, at least in its more traditional manifestations, and studies of immigration to the South are also driven by different political projects. Southern studies operates through a powerful discursive formation: a South contoured by a black-white binary; reshaped by the experiences of institutionalized racism, racial struggle, and violence; and in a more positive vein, authenticated through particular cultural practices (e.g., biscuits, barbecue, the blues). Studies of immigration to the South, by contrast, coalesce around a political project of drawing attention and legitimacy to immigrants’ presence, needs, and contributions, setting aside contextualization or implications with regard to the South’s historical and cultural geographies of race. Insofar as each pursues an implicitly celebratory project (the uniqueness of the South vs. the significance of immigrants’ needs and contributions), they seek to protect the purview and integrity of the subject that they construct.

Although southern studies and studies of immigration to the South have yet to speak in a sustained dialogue, within many southern locales, the worlds they examine increasingly entangle. In places where long-term residents and new immigrants interact, the South’s history of a black-white binary, racial discrimination, and struggles toward racial justice intertwine with new demographic realities in ways that change both the politics of immigrant reception and experiences and the local and regional contours of racial politics. To understand these sites of entanglement, southern studies and migration studies must be brought together in an interdisciplinary framework that can account for the empirical reality of their overlap. The remainder of this article examines three vignettes, illustrating some ways of approaching these new demographic and representational realities. Through them we consider how the story of immigrant settlement reconfigures understandings and mobilizations of the South’s past to comprehend the present and impact the future.

Nashville: Old Water Fountains in New Times

Nashville, like many southern cities, began to experience notable immigrant settlement in the mid to late 1990s. As its downtown “revitalized” and its bedroom communities expanded into adjacent counties, a booming residential and commercial construction industry developed across the city, attracting immigrant labor. At the same time, Nashville’s service economy grew and created new demand for low-wage workers. The Music City in the late-twentieth century offered much to Latino migrants: readily available work, relatively affordable housing, and, at least initially, little open hostility toward immigrant residents and neighborhoods. Although Nashville had a small but politically visible refugee population dating to the Cuban crisis and including older Vietnamese and Kurdish communities, as well as newer groups from a range of global hotspots, the arrival of Spanish-speaking immigrants, both directly from Latin America and secondarily from other US locales, quickly dwarfed the city’s refugee population, becoming the dominant image of Nashville’s ‘new sonido.’12For research on immigration to Nashville, see Jamie Winders, “Placing Latinos in the Music City: Latino Migration and Urban Politics in Nashville, Tennessee,” in Latinos in the New South, ed. Smith and Furuseth; Winders, “‘New Americans’ in a ‘New South’ City?;” and Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?.”

|

| Stan Schnier, A woman at the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride holds a sign that asks “What color is an immigrant?”, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, New York, New York, October 4, 2003. |

Recent Census estimates suggest that almost twelve percent of Nashville’s population is foreign born, slightly below the national average of 12.5 percent. Across Nashville-Davidson County, approximately eight percent of the population is Hispanic or Latino, a percentage that has grown rapidly in the last ten years.13Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2009. 2009 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. US Census Bureau.

http://factfinder.census.gov/legacy/aff_sunset.html?_bm=y&-context=adp&-qr_name=ACS_2009_1YR_G00_DP2&-ds_name=ACS_2009_1YR_G00_&-tree_id=309&-redoLog=true&-_caller=geoselect&-geo_id=16000US4752006&-format=&-_lang=en Accessed 1 November 2010. Immigration has become a hot topic in Nashville, evident in the defeated 2008 referendum on English-only legislation and an overall reconfiguration of the city’s low-wage labor market. Nashville’s politics of immigrant settlement often play out most intensely in less publicized, everyday spaces, from the corner store to the classroom.14For discussion of the politics of immigration in the spaces of daily life, see David Ley, “Between Europe and Asia: The Case of the Missing Sequoias.” Ecumene 2 (1995): 185-210; and Smith and Winders, “We’re Here to Stay.” In Jamie Winders’ research on public schools in southeast Nashville, where there is the greatest concentration of immigrant residents, teachers repeatedly discussed the collision of southern past, present, and future in their classrooms. In teaching about the civil rights movement, as one elementary-school teacher reported, students ask, “Which water fountain would I be able to drink from?” Conjuring images of Jim Crow, a separate-but-unequal color line, and transgression, the question is grounded in a racial ontology in which the answer was always the “good” water fountain marked “white” or the offshoot marked “colored.” Under Jim Crow even children knew how to answer this question. That knowing was the bedrock of a southern, indeed national, grammar of race and place.

What happens when the student asking this question is a child of Egyptian refugees relocated to Nashville or a recently settled Mexican family? Or when this question is asked in elementary schools with large Latino and smaller Kurdish, Vietnamese, Somali, and Sudanese populations? To answer it, teachers in southeast Nashville translate a binary system of racial difference and segregation for children for whom Nashville has always been a multicultural mix of Kurdish and Egyptian families, Sudanese refugees, Mexican children, Honduran men, and a sprinkling of white and black residents. For immigrant children in Nashville, the multiethnic present makes the biracial past seem incomprehensible. As teachers work to translate garbage strikes and segregated fountains to Latino children who look for the “Spanish people” alongside King, and as young students try to understand an old system of difference through their present experiences, these translations reshape southern history and present. In these classrooms, students inadvertently defy silences about the South’s new racializations while lacking the ability to place themselves within its shifting social and racial hierarchies.

These questions raised by children in search of their “place” within southern history, present, and future highlight the tangible impacts of an immigrant presence not only on southern cities like Nashville but also on overarching frameworks for understanding southern past and present. What are the implications of a generation of new southern residents for whom a past in black and white seems all but unbelievable? How will broader understandings and critical examinations of southern history adjust? In southern locales such as Nashville, the cord between past and present is fraying and being rethreaded in public schools, low-wage worksites, and residential neighborhoods, as students, workers, and residents make sense of each other and, in the process, their place in southern past and present. As a southern history of a black-white racial hierarchy that produced segregations and oppressions is joined by a multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual southern present with its own racial and class inequalities, past and contemporary color lines are interwoven in ways that confound dominant understandings of the South. Southern studies, as currently configured, cannot account for this degree of variation and change.

Memphis: Minority Politics and Class Divisions

|

| Jeffrey Rohan, National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee, August 14, 2010. |

The contemporary racial politics and historical memories of racism that inform responses to immigrants in Memphis contrast sharply with those in Nashville. Such differences illustrate a spatial variability that confounds generalizations about the South and mandates contextualization of contemporary migration. Tied economically and culturally to the Delta’s plantation system and governed for decades by the authoritarian paternalism of Boss Crump, Memphis is Deep South, the “largest city in Mississippi,” as some locals put it. As the site of King’s assassination in 1968 and the lynchings that provoked Ida B. Wells’ famous crusade decades earlier (for which she was forced to flee), Memphis has witnessed extreme racist violence and bitter struggles over white supremacy.15Miriam DeCosta-Willis, The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells (Boston: Beacon, 1995); and Michael Honey, Black Labor and Southern Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1993). Contestations over historical commemoration, focused recently on the National Civil Rights Museum in the Lorraine Motel where King was shot, re-enact these struggles even as they seek to represent them. Memphis is a city steeped in race.16John Paul Jones III, “The Street Politics of Jackie Smith,” in A Companion to the City, ed. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (Malden MA: Blackwell Pub, 2000).

Latino immigrants began arriving in Memphis in large numbers during the 1990s, drawn by jobs in the city’s burgeoning construction and distribution sectors. Long an important stopover for the movement of goods and people along the Mississippi River and across the continental United States, Memphis has become a center for the worldwide distribution of air freight. As the global economy expanded during the 1990s, the FedEx Corporation, headquartered here, grew from a relatively small niche market in overnight package delivery into a global logistics empire. Around the city’s perimeter, warehouses storing goods for "just-in-time" delivery mushroomed in industrial parks. The demand for labor in new construction and warehousing (or distribution) attracted migrants, primarily from Latin America, who often found higher wages in this southern city than in Los Angeles and other historic immigrant gateways.17See Smith, Mendoza and Ciscel, “The World on Time.”

Memphis’ new immigrants arrived in the wake of a bitter election that brought the first African American mayor, W. W. Herenton, to power in 1991.18Marcus Pohlmann and Michael Kirby, Racial Politics at the Crossroads: Memphis Elects Dr. W.W. Herenton (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1996). Herenton’s campaign ignited white anxieties about “black rule” and further propelled white flight. In this increasingly majority-black city, he was re-elected handily and repeatedly. As in other southern locales, Memphis’s growing immigrant population attracted little attention during mayoral campaigns, which unfolded along familiar black-white lines complicated by class. Major controversy erupted, however, in 1997, when Hispanic business leaders approached Herenton about inclusion in special municipal contracting programs for minorities. Herenton repudiated their claims by referencing the history of African American slavery and Jim-Crow segregation, suggesting that Latinos’ experience of racial oppression was insufficient for redress through government affirmative action. Ironically, the Latino businesspeople drawing attention to Memphis’ expanding Hispanic population were, in most cases, US born and/or highly acculturated. Their understanding of race, intentional group positioning in racial terms, and efforts to access race-specific remedies attested to their distance from most Latino immigrants, who rarely sought to identify themselves in racial terms for the purpose of political organizing and instead lived and worked in the recesses of Memphis’ economy and neighborhoods.

Complicated racial politics lay behind Herenton’s rejection of Latino claims to minority status. Like many leaders of large urban centers, he presided over a place of deep and seemingly intractable black poverty at a time of declining federal assistance and escalating white flight. Herenton, however, could appear to champion the interests of poor and working-class African Americans who gave him votes, even as he failed to improve their quality of life, when he refuted Latino claims to affirmative action in the name of longstanding black oppression. Exploiting this dispute, white contractors in Memphis sought to eliminate affirmative action in public contracts altogether, legitimating Herenton’s protective stance in the eyes of many black residents and further embittering the city’s racial politics.19See the discussion in Smith, “Across Races and Nations.” Through this and other episodes, Latino racialization and group positioning unfolded in Memphis, challenging overarching representations of the South in racially binary terms and illustrating the complicated interplay of race, class, and national origin.

Contestations over Latino access to racially-targeted remedies have erupted elsewhere in the South, raising thorny questions.20In 2001, for example, a white Georgia legislator introduced a measure into the state legislature to expand the official definition of “minority.” At stake was a small tax break granted to state contractors who sub-contracted to minority-owned businesses. Georgia’s Black Caucus split over its response. Echoing Herenton, one African American legislator asserted, “Many Hispanics are not people of color. They are a language group, an ethnic group. These people never experienced the same things we did.” Others, however, including some with strong credentials derived from their roles in the civil rights movement, disagreed. Rep. Tyrone Brooks of Atlanta, for example, urged, “We’ve got to expand the tent.” White legislators were also divided. Opponents of affirmative action tended to reject the inclusion of Latinos in the definition of “minority.” Others, however, mindful of the Latino electorate’s escalating size and influence, were in favor. In 2002, the bill became law. See Ellen Griffith Spears, “Civil Rights, Immigration, and the Prospects for Social Justice Collaboration,” in Peacock, Watson and Matthews, 235-246. Who should benefit from remedies that ensue from the civil rights movement? Do Latinos, despite census definitions to the contrary, constitute a race; and if so, should they be treated in the same way as African Americans, particularly in a southern context? Should Latino immigrants be encouraged to understand and position themselves in the South’s bipolar racial hierarchy; and if so, where? As in Nashville, how can Memphis address the deeply entrenched color line while responding to new color lines whose boundaries are still being formed? What transformations are required of southern studies to account for these highly variable, context-specific intersections of different systems of inequality?

In Memphis, the class privilege of Latinos who publicly advocated for inclusion as minorities, as well as their ability to identify as white, obscure the disadvantages experienced by many recent, darker-skinned Latino immigrants, who typically are neither business owners nor well-to-do. Who, then, can and should speak for an immigrant population sliced by lines of class, nationality, gender, language, and citizenship status? As our final vignette shows, diverse advocacy organizations are engaging these questions, bumping up against immigration’s ill fit within current understandings of the South.

New Immigrant Activism and an Old Playbook

|

| Billboard sponsored by the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition, a group that supports immigration, Nashville, Tennessee, 2009. |

Mainstream immigrant-advocacy groups like the National Immigration Forum have long based their appeals on a comfortingly egalitarian version of US history as “a nation of immigrants.” In the nuevo South of the early 2000s, as activists mobilized local and statewide organizations to advocate for immigrant needs and rights, they often adopted similar rhetorical strategies. In Tennessee groups waged campaigns that asked residents to “embrace the immigrants they once were.” The implicit racial content of this appeal, which presumes that all Tennesseeans share the same past and want to revisit it, may have resonated with whites; but it suppressed histories of slavery, genocide, colonialism, and forced migration disproportionately linked to people of color, not all of whom identify as “immigrant.” Although such strategies could take place in many locations with growing immigrant populations and intensifying hostility toward them, the uneasy political and rhetorical relationship between immigrant rights and more race-conscious, anti-racist organizing evident in this campaign is particularly pointed in the South, where the meeting ground between current immigrant-rights advocacy and the historic civil rights movement is uncharted, unclear, but unavoidable.

One effort to situate immigrant rights within a civil rights legacy was the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride (IWFR) of fall 2003. Conceived in the wake of September 11, 2001, when the presumed equation between immigration and terrorism provoked nativist responses across the country and reversed momentum toward immigration reform, the IWFR was designed to galvanize the immigrant-rights movement by strengthening its relationship to organized labor and less directly, civil rights and other faith- and community-based organizations. The original plan was to take one bus of riders through eight cities, but enthusiasm for the idea led to a more ambitious outcome. Eighteen buses originated from ten cities and carried nine-hundred riders along different routes through more than a hundred US cities. The riders converged to lobby Congress, before rallying with a hundred-thousand supporters in a demonstration in Queens, New York.21Francis Calpotura, “Riding with the Wind,” ColorLines 7, no. 1 (2004): 5-7; and Spring Miller, “A Report from Nashville on the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, 2003,” Enlaces News, January, 2004.

|  |

| Associated Press, Map of 1961 Freedom Rides Routes, February 1962. | Map of 2003 Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride Routes. Courtesy of Immigrant Freedom Workers Ride Coalition. |

The primacy of the desired link between immigrant rights and organized labor may account in part for the IWFR’s uneven engagement with the legacies of the civil rights movement, as well as for its failure to confront the sometimes-uneasy relationship between immigrant rights and anti-racist organizing. For the IWFR, the civil rights movement stood largely as a symbolic historical resource that this new initiative could mobilize. As one rider from Houston remarked, the IWFR “purposefully traveled through the South to get the blessings of African American leadership, and to draw on the legitimacy and unassailable moral standing of the civil rights movement.”22Calpotura, “Riding,” p. 6. Although many bus routes never entered the South, those that did included stops in places such as Memphis, Nashville, Selma, and Atlanta, selected for their significance to the civil rights movement. The expectation that legendary civil rights leaders would endorse the IWFR was largely fulfilled, at least by those who spoke at rallies organized to greet the new Riders. In Mississippi, the president of the state chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference exhorted the crowd: “I don’t care if you came from the Mayflower or crossed the border last night. You are entitled to the same human rights as I. You are my brother. You are my sister. You are my people. The fight for freedom is not over.”23Ibid.

At the local level, the extent to which the IWFR spurred new alignments between the causes of immigrant rights and anti-racist organizing varied widely. A report from Nashville indicated that the Ride’s planning process was a “rich exercise in dialogue and coalition-building” among immigrant-rights, labor, and black community leaders.24Miller, “Report,” p. 1. Reverend Jim Lawson, who played a central role in Nashville’s civil rights struggles in the late 1950s and early 1960s, spoke to the Riders and their supporters, giving the mantle of his moral authority to their cause. In Memphis, however, no organization seized the IWFR as an opportunity for organizing or coalition building; and the Riders’ visit to sites like the National Civil Rights Museum drew relatively small crowds. Once again, the ground-level politics of race and immigration were highly dependent on local contexts, in this case local labor, civil rights, and other relevant organizations.

Moreover, the extent to which African American southerners believe that the legacies of the civil rights movement do or should encompass immigrant rights is unclear, as is the extent to which there is recognition of mutual grievances between the two groups. Evidence points to mutual misrecognition and occasional antagonism between African Americans and Latinos in some parts of the South.25Paula D. McClain et al., “Racial Distancing in a Southern City: Latino Immigrants’ Views of Black Americans,” Journal of Politics 68, no. 3 (2006): 571-584. With the goal of recognizing and building on the “common struggle against oppression and racism that immigrants and African Americans in Tennessee share,” the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition (TIRRC) launched a project called “Black, Brown and Beyond.” At the same time, however, TIRRC spearheaded a “Welcoming Tennessee Initiative,” proclaiming that “We believe that Tennesseans remember, honor, and value our immigrant roots.” The simultaneity of these two initiatives unintentionally highlighted the ambiguities associated with efforts to position immigrants in the South’s contentious racial history and present. While calling for black-brown alliances that build on mutual, if distinct, oppressions and struggles, TIRRC reinforces the notion that all Tennesseans share and value a sanitized version of America’s immigrant history as entirely voluntary.

Because the appeal to a white-washed immigrant history is directed at a white audience of business leaders, political officials, and opinion makers, rather than at immigrants themselves, it may not represent immigrants’ (or African Americans’) claims or sense of identity vis-à-vis the United States and their “place” within it. Nonetheless, the incompatibility between the pasts that the immigrant rights/civil rights alliance seeks to join – one of immigrant triumph to be “honored,” another of racial oppression to be “overcome”– gestures toward the damning reality that throughout US history, diverse immigrant groups have claimed a position in the racial hierarchy at the expense of African Americans. Equally important, the landless Latino farmers and workers who cross the US–Mexico border in search of livelihoods in the South bring pasts that partake far more of racial oppression (and colonialism, political repression, and genocide, as well as ongoing resistance) than of the triumphalist stories of white ethnics. Do these new immigrants draw on such pasts to locate themselves within the South’s racial histories? Might their histories reconfigure yet again what constitutes “the South”? Or, will new immigrants position themselves in the white-washed immigrant saga of ethnic groups who achieved success by ceasing to be “not white”?26For discussion of immigrants in the US racial hierarchy, see Barrett and Roediger, “In-between Peoples.”

Conclusion

In 1988, Light Townsend Cummins called for a bridge between southern historians who ignore the South’s Spanish heritage and European and Latin American scholars who overlook its post-Hispanic history. Paralleling the experiences of African Americans and Hispanics in southern states, he concluded that “Hispanic southerners present a profitable field for research by those who wish to examine ethnicity and its rich history in the American South.” Fast-forwarding into the nineteenth century, Rowland Berthoff documented the recruitment of immigrant workers into the post-Civil War South in an effort to discipline black workers. Although Berthoff concluded that such efforts were “a minor and futile phase of the New South,” the same cannot be said about the nuevo South in which an immigrant presence is neither minor nor temporary.27Cummins, “The Hispanic Heritage,” 110; Berthoff, “Southern Attitudes Toward Immigration,” 360.

By urging approaches that historicize immigration, race, and place, by interrogating the South’s historical meanings and usefulness for different constituencies, and by comparing immigration experiences across southern locales, we extend Cummins’ call and suggest that current immigrants enter and interrogate the South’s present and past through their indigenous, African, and Spanish hybridities and histories. Insofar as such a move may produce contestations over everything from the meaning and demarcation of the South to the periodization of its history, it carries destablizing implications for southern studies. As Edward Ayers reminds us, however, “There was never a time when Southern culture developed secure from the outside, when people knew just where the borders were, when people knew just what the South was and was not.”28Edward Ayers, “What We Talk About When We Talk About the South,” in All over the Map: Rethinking American Regions, ed. Edward Ayers, Patricia Nelson Limerick, Stephen Nissenbaum, and Peter Onuf (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1996), 74. To exclude immigrants from that which is southern renders immigrants and the South incompatible, incongruous, and mutually exclusive.

We recognize that our call could be interpreted as an effort to sideline the persistence of anti-black racism. There is well-founded concern among African American leaders that with a shrinking pool of economic resources, diminished political visibility, and a color-blind discourse of happy multiculturalism, a focus on immigrant rights and needs can push anti-black racism and discrimination, as well as the situation of African American communities, out of the limelight.29Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?” Within some worksites, anecdotal information points to the use of both ethnic and racial differences to divide workers and a precarious immigrant workforce to deepen black working-class dispossession, especially in times of economic crisis.30Barbara Ellen Smith, “Market Rivals or Class Allies? Relations between African American and Latino Immigrant Workers in Memphis,” in Shefner and Ansley, 299-317. Nonetheless, we also find echoes of African Americans’ oppression among new immigrants who experience racial profiling, intensive labor exploitation, white supremacist violence, and denial of civil rights.31Southern Poverty Law Center, “Under Siege: Life for Low-Income Latinos in the South,” April 2009.

http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/publications/under-siege-life-for-low-income-latinos-in-the-south Acessed 1 November 2010. These reverberations remind us that a multi-racial/ethnic present is the future and we deny that reality and its links to southern history at our peril.

By historicizing immigration to the South, then, we mean, first, marking an earlier starting point for questions about community change vis-à-vis immigration. As our vignettes illustrate, immigration and responses to it have telescoped the distance between southern past, present, and future. Paying closer attention to the mobilization of southern pasts to frame an immigrant presence helps us understand the complex politics of immigrant incorporation and reception across the South. Second, we mean scrutinizing historical echoes, such as those articulated by Herenton in Memphis, in contemporary discussions and experiences of immigration. Migration scholars miss much about immigration’s ground-level dynamics in southern communities if they do not recognize and pursue the ways in which the racial past is mobilized by southerners, black and white, to interpret and position immigrants. Finally, by historicizing immigration, we mean examining the mechanisms that allow particular narratives of race, place, and the past to become dominant, to the exclusion of other narratives, especially those produced by racialized “others,” including immigrants. Reflecting on whose version of southern history (and which version of the South) is allowed to become dominant in framing an immigrant presence helps us understand the broader power geometries within which immigrant and other marginalized communities seek to make a place.

Absent such historicization, the story of immigration to the South will remain incoherent not simply or even primarily because it is ongoing but also because it does not possess a coherent plot. It has, in other words, yet to become a southern story that both partakes of and is incorporated within regional meanings, identities, histories, and self-representations. Our vignettes illuminate the illegibility of a Latino presence within southern stories and point to a fundamental reason for it: Latinos cannot be rendered “southern” because they remain incommensurable within, and implicitly challenge, southern histories organized through defining racial difference between black and white.

To be sure, immigrants, particularly Latinos, increasingly appear in demographic profiles of the South, their music, food, and cultural practices providing intrigue for both academic and popular renderings of the cosmopolitan and globalized South. As Homi Bhabha reminds us, however, superficial acknowledgement of diversity is not the same as deep engagement with difference. Simply adding a Latino presence to register diversity does not constitute recognition of the difference that immigration potentially makes to southern racial politics and projects.32Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London; New York: Routledge, 1994). Much is at stake in this impasse. Insofar as immigrants are subject to the “deep structure of racial reasoning” that situates them within the traditional racial hierarchies deemed southern, how can we draw on and re-draw history to illuminate, these processes of racialization?33Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “Open Secrets: Memory, Imagination, and the Refashioning of Southern Identity,” American Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1998): 113. Insofar as immigrants seek to situate themselves within the civil rights movement’s anti-racist appeals, how can that movement’s legacy be understood to encompass their needs and demands? What would an effective, racially and historically sensitive, southern immigrant-rights strategy look like?

Acknowledgments

Portions of this article were presented at the 2009 Association of American Geographers meetings, the 2009 Southern Sociological Society meetings, and the 2010 St. George Tucker Society meetings. We thank Carl Bankston, Peggy Hargis, Louis Kyriakoudes, Jennifer Bickham Mendez, Laura Pulido, and Clyde Woods for their feedback at these gatherings. We also thank Allen Tullos and two anonymous reviewers for their close readings and commentary on our arguments.

Recommended Resources

Ansley, Fran and Jon Shefner, eds. Global Connections and Local Receptions: New Latino Immigration to the Southeastern US. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009.

Cobb, James and William Stueck, eds. Globalization and the American South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005.

Peacock, James L., Harry L. Watson, and Carrie R. Matthews, eds. The American South in a Global World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Massey, Douglas, ed. New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008.

Smith, Heather and Owen Furuseth, eds. Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place. Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006.

Zúñiga, Víctor and Rubén Hernández-León, eds. New Destinations of Mexican Immigration in the United States: Community Formation, Local Responses and Inter-Group Relations. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2005.

Links

Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride

http://www.aflcio.org/aboutus/thisistheaflcio/publications/magazine/0903_iwfr.cfm.

Kochhar, Rakesh, Roberto Suro, and Sonya Tafoya. "The New Latino South: The Context and Consequences of Rapid Population Growth," (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center, 26 July 2005)

http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=50.

Southern Poverty Law Center Immigrant Justice Project

http://www.splcenter.org/legal/ijp.jsp.

Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition (TIRRC)

http://www.tnimmigrant.org/history/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Although in this article, we focus on Latino migration (a ‘nuevo’ South), we acknowledge the presence of smaller immigrant and refugee populations, some of which have long histories in the South. These groups have impacted racial and social formations in some southern locales and are the subject of such recent studies as Mark Moberg and Stephen Thomas, “Indochinese Resettlement and the Transformation of Identities Along the Alabama Gulf Coast” and Choony Soon Kim, “Asian Adaptations in the American South,” in Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South: Anthropological Contributions to a Region in Transition, ed. Carole Hill and Patricia Beaver (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998); Deborah Duchon, “Home Is Where You Make It: Hmong Refugees in Georgia,” Urban Anthropology 26, no. 1 (1997): 71-92; David Reimers, “Asian Immigrants in the South,” in Globalization and the American South, ed. James Cobb and William Stueck (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005); and Jin-Kyung Yoo, “Utilization of Social Networks for Immigrant Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Korean Immigrants in the Atlanta Area,” International Review of Sociology 10, no. 3 (2000): 347-363. |

|---|---|

| 2. | The reference to the “past isn’t dead” originates with Williams Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1951). For an academic examination of historical narratives that influence the present, see Ewen Hague et al., “Whiteness, Multiculturalism and Nationalist Appropriation of Celtic Culture: The Case of the League of the South and the Lega Nord,” Cultural Geographies 12, no. 2 (2005): 151-173. For a more popular approach to similar themes, see Jim Webb, Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (New York: Broadway Books, 2004). For discussions of the Civil War, see Curt Anders, Hearts in Conflict: A One-Volume History of the Civil War (Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub. Group, 1994). For discussions of African American history, see Kenneth Goings and Raymond Mohl, eds., The New African-American Urban History (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996). For discussions of the contemporary South and southern distinctiveness, see Larry Griffin and Don Doyle, eds., The South as an American Problem (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995); Dewey Grantham, The South in Modern America: A Region at Odds (New York: Harper Collins, 1994); and James Cobb and William Stueck, eds., Globalization and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005). |

| 3. | Cobb and Stueck, Globalization and the American South; Barbara Ellen Smith, Marcela Mendoza, and David Ciscel, “‘The World on Time:’ Flexible Labor, New Immigrants and Global Logistics,” in The American South in a Global World, ed. James Peacock, Harry Watson and Carrie Matthews, 23-38 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005). |

| 4. | Larry Griffin, Ranae Evenson, and Ashley Thompson, “Southerners All?,” Southern Cultures 11, no. 1 (2005): 6-25. |

| 5. | See, for example, Barbara Ellen Smith and Jamie Winders, “‘We’re Here to Stay’: Economic Restructuring, Latino Migration, and Place-Making in the U.S. South,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 33 (2008): 60-72; Barbara Ellen Smith, “Across Races and Nations: Social Justice Organizing in the Transnational South,” in Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place, ed. Heather Smith and Owen Furuseth, 235-256 (Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006); Jamie Winders, “Changing Politics of Race and Region: Latino Migration to the U.S. South,” Progress in Human Geography 29, no. 6 (2005): 683-699; Jamie Winders, “‘New Americans’ in a ‘New South’ City? Immigrant and Refugee Politics in the Music City,” Social and Cultural Geography 7, no. 3 (2006): 421-435; and Jamie Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture? Race, Latino Migration, and Urban Politics in Nashville, Tennessee,” Urban Geography 29, no.3 (2008): 246-263. |

| 6. | An exception to the failure to historically contextualize immigration to the South is Rubén Hernández-León and Víctor Zúñiga, “Appalachia Meets Aztlán: Mexican Immigration and Inter-Group Relations in Dalton, Georgia,” in New Destinations of Mexican Immigration in the United States: Community Formation, Local Responses and Inter-Group Relations, ed. Víctor Zúñiga and Rubén Hernández-León, (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2005). |

| 7. | Richard Fry, Latino Settlement in the New Century, October 23, 2008 (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center), http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/96.pdf. For discussions of immigration to the South, see Carl Bankston III, “New People in the New South: An Overview of Southern Immigration,” Southern Cultures 13, no. 4 (2007): 24-44; Peacock, Watson and Matthews, eds., The American South in a Global World; Holly Barcus, “The Emergence of New Hispanic Settlement Patterns in Appalachia,” The Professional Geographer 59, no. 3 (2007): 298-315; Furuseth and Smith, Latinos in the New South; Zúñiga and Hernández-León, New Destinations; Helen Marrow, “New Destinations and the American Colour Line,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32, no. 6 (2009): 1037-1057; Benjamin Shultz, “Inside the Gilded Cage: The Lives of Latino Immigrant Males in Rural Central Kentucky,” Southeastern Geographer 48, no. 2 (2008): 201-218; Robert Yarbrough, “Latino/White and Latino/Black Segregation in the Southeastern United States: Findings from Census 2000,” Southeastern Geographer 43, no.2 (2003): 235-248; Fran Ansley and Jon Shefner, eds., Global Connections and Local Receptions: New Latino Immigration to the Southeastern US, (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009); and Douglas Massey, ed., New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration, (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008). |

| 8. | For work on Latino migration to the rural South, see Peter Benson, “El Campo: Faciality and Structural Violence in Farm Labor Camps,” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 4 (2008): 589-629; and Josh McDaniel and Vanessa Casanova, “Pines in Lines: Tree Planting, H2B Guest Workers, and Rural Poverty in Alabama.” Southern Rural Sociology 19, no.1 (2003): 73-96. For work on the geographic diversity of Latino migration to the South, see James Elliott and Marcel Ionescu, “Postwar Immigration to the Deep South Triad: What Can a Peripheral Region Tell Us About Immigrant Settlement and Employment?” Sociological Spectrum 23 (2003): 159-180; Laurel Fletcher et al., “Rebuilding after Katrina: A Population-Based Study of Labor and Human Rights in New Orleans.” International Human Rights Law Clinic, Boalt Hall School of Law, and Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, and Payson Center for International Development and Technology Transfer, Tulane University (June 2006). For work on Latino labor-market participation, see Steve Striffler, “Neither Here Nor There: Mexican Immigrant Workers and the Search for Home.” American Ethnologist 34, no.4 (2007): 674-688. For work on Latino migration to southern cities, see Qingfang Wang and Wei Li, “Entrepreneurship, Ethnicity and Local Contexts: Hispanic Entrepreneurs in Three U.S. Southern Metropolitan Areas,” GeoJournal 68 (2007): 167-182; Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?;” and Yarbrough, “Latino/White and Latino/Black Segregation.” |

| 9. | Alejandro Portes and Alex Stepick, City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami (Berkeley: University of California, 1993); Rachel Buff, Immigration and the Political Economy of Home: West Indian Brooklyn and American Indian Minneapolis (Berkeley: University of California, 2001). |

| 10. | Jamie Winders and Barbara Ellen Smith, “Excepting/Accepting the South: New Geographies of Latino Migration, New Directions in Latino Studies.” Latino Studies, under review; and Susan Greenbaum, “Urban Immigrants in the South,” in Hill and Beaver, Cultural Diversity. For discussion of the South outside a black-white binary, see Rowland Berthoff, “Southern Attitudes Toward Immigration,1865-1914,” Journal of Southern History 17, no. 3 (1951): 328-360; Light Townsend Cummins, “The Hispanic Heritage of the Southern United States of America,” Revista de historia de America 10, no. 5 (1988): 89-110; and Julie Weise, “Mexican Nationalisms, Southern Racisms: Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the U.S. South,1908-1939,” American Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2008): 749-777. For discussion of immigration and US racial politics, see Gabriela Arrendondo, “Navigating Ethno-Racial Currents: Mexicans in Chicago,1919-1939,” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 3 (2004): 399-427; and James Barrett and David Roediger, “In-between Peoples: Race, Nationality, and the ‘New Immigrant’ Working Class,” Journal of American Ethnic History 16, no. 3 (1997): 3-44. |

| 11. | For works in southern studies, see Edward Ayers, “Narrating the New South,” The Journal of Southern History 61, no. 3 (1995): 555-566; Griffin and Doyle, The South as an American Problem, and Jennifer Rae Greeson, “The Figure of the South and the Nationalizing Imperatives of Early United States Literature,” The Yale Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (1999): 209-248. For works on southern immigration, see Carl Bankston III et al., Sociological Spectrum 23 (2003); Altha Cravey, “Desire, Work and Transnational Identity,” Ethnography 6, no. 3 (2005): 357-383; Arthur Murphy, Colleen Blanchard, and Jennifer Hill, eds., Latino Workers in the Contemporary South, (Athens: University of Georgia, 2001); Smith and Furuseth, Latinos in the New South; Winders, “Changing Politics of Race and Region”; Terry Easton, “Geographies of Hope and Despair: Atlanta’s African American, Latino, and White Day Laborers,” Southern Spaces, December 21, 2007. For engagement with the cultural politics of immigration to the South, see Mary Odem, “Our Lady of Guadalupe in the New South: Latino Immigrants and the Politics of Integration in the Catholic Church,” Journal of American Ethnic History 24, no. 1 (2004): 26-57; and also Mary Odem, Global Lives, Local Struggles: Latin American Immigrants in Atlanta,” Southern Spaces, May 19, 2006. |

| 12. | For research on immigration to Nashville, see Jamie Winders, “Placing Latinos in the Music City: Latino Migration and Urban Politics in Nashville, Tennessee,” in Latinos in the New South, ed. Smith and Furuseth; Winders, “‘New Americans’ in a ‘New South’ City?;” and Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?.” |

| 13. | Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2009. 2009 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. US Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov/legacy/aff_sunset.html?_bm=y&-context=adp&-qr_name=ACS_2009_1YR_G00_DP2&-ds_name=ACS_2009_1YR_G00_&-tree_id=309&-redoLog=true&-_caller=geoselect&-geo_id=16000US4752006&-format=&-_lang=en Accessed 1 November 2010. |

| 14. | For discussion of the politics of immigration in the spaces of daily life, see David Ley, “Between Europe and Asia: The Case of the Missing Sequoias.” Ecumene 2 (1995): 185-210; and Smith and Winders, “We’re Here to Stay.” |

| 15. | Miriam DeCosta-Willis, The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells (Boston: Beacon, 1995); and Michael Honey, Black Labor and Southern Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1993). |

| 16. | John Paul Jones III, “The Street Politics of Jackie Smith,” in A Companion to the City, ed. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (Malden MA: Blackwell Pub, 2000). |

| 17. | See Smith, Mendoza and Ciscel, “The World on Time.” |

| 18. | Marcus Pohlmann and Michael Kirby, Racial Politics at the Crossroads: Memphis Elects Dr. W.W. Herenton (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1996). |

| 19. | See the discussion in Smith, “Across Races and Nations.” |

| 20. | In 2001, for example, a white Georgia legislator introduced a measure into the state legislature to expand the official definition of “minority.” At stake was a small tax break granted to state contractors who sub-contracted to minority-owned businesses. Georgia’s Black Caucus split over its response. Echoing Herenton, one African American legislator asserted, “Many Hispanics are not people of color. They are a language group, an ethnic group. These people never experienced the same things we did.” Others, however, including some with strong credentials derived from their roles in the civil rights movement, disagreed. Rep. Tyrone Brooks of Atlanta, for example, urged, “We’ve got to expand the tent.” White legislators were also divided. Opponents of affirmative action tended to reject the inclusion of Latinos in the definition of “minority.” Others, however, mindful of the Latino electorate’s escalating size and influence, were in favor. In 2002, the bill became law. See Ellen Griffith Spears, “Civil Rights, Immigration, and the Prospects for Social Justice Collaboration,” in Peacock, Watson and Matthews, 235-246. |

| 21. | Francis Calpotura, “Riding with the Wind,” ColorLines 7, no. 1 (2004): 5-7; and Spring Miller, “A Report from Nashville on the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, 2003,” Enlaces News, January, 2004. |

| 22. | Calpotura, “Riding,” p. 6. |

| 23. | Ibid. |

| 24. | Miller, “Report,” p. 1. |

| 25. | Paula D. McClain et al., “Racial Distancing in a Southern City: Latino Immigrants’ Views of Black Americans,” Journal of Politics 68, no. 3 (2006): 571-584. |

| 26. | For discussion of immigrants in the US racial hierarchy, see Barrett and Roediger, “In-between Peoples.” |

| 27. | Cummins, “The Hispanic Heritage,” 110; Berthoff, “Southern Attitudes Toward Immigration,” 360. |

| 28. | Edward Ayers, “What We Talk About When We Talk About the South,” in All over the Map: Rethinking American Regions, ed. Edward Ayers, Patricia Nelson Limerick, Stephen Nissenbaum, and Peter Onuf (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1996), 74. |

| 29. | Winders, “An ‘Incomplete’ Picture?” |

| 30. | Barbara Ellen Smith, “Market Rivals or Class Allies? Relations between African American and Latino Immigrant Workers in Memphis,” in Shefner and Ansley, 299-317. |

| 31. | Southern Poverty Law Center, “Under Siege: Life for Low-Income Latinos in the South,” April 2009. http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/publications/under-siege-life-for-low-income-latinos-in-the-south Acessed 1 November 2010. |

| 32. | Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London; New York: Routledge, 1994). |

| 33. | Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “Open Secrets: Memory, Imagination, and the Refashioning of Southern Identity,” American Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1998): 113. |